As most of you probably know, the Federal Reserve announced yesterday that:

“Chairman Ben S. Bernanke will hold press briefings four times per year to present the Federal Open Market Committee’s current economic projections and to provide additional context for the FOMC’s policy decisions.”

The announcement, I think, makes the intent of these press conferences abundantly clear:

“The introduction of regular press briefings is intended to further enhance the clarity and timeliness of the Federal Reserve’s monetary policy communication. The Federal Reserve will continue to review its communications practices in the interest of ensuring accountability and increasing public understanding.”

Communications, accountability, and credibility are being tested at the moment, as aptly described in a New York Times op-ed from former Fed Governor Larry Meyer (no registration required if you link via Real Time Economics):

“Any American who has shopped for groceries or pumped gasoline in the last few months knows that prices for food and energy have been soaring. Demand from fast-growing Asian economies is one major contributor to price increases; the turmoil in the Middle East is another.

“All of this has made some economists and lawmakers in the United States nervous. They fear that higher prices for commodities will translate into higher prices for all goods and services and that the Federal Reserve, by ignoring commodity prices, has become lax on inflation.”

Furthermore, Meyer clearly indicates what can go wrong:

“… during the 1970s and early 1980s, an era of debilitating inflation, the markets had no confidence in the Fed’s ability to keep prices stable. This meant that any increase in prices, including those for volatile items like food and energy, were almost immediately and fully translated into expectations of higher overall inflation in the future. Those expectations, in turn, gave rise to actual increases in other prices, not just food and energy. (If workers expect that inflation will be 2 percent in the coming year, they will demand a wage increase that is 2 percentage points higher than they otherwise would to keep improving their standard of living.)

“So in the ’70s, increases in food and gas prices affected both core and overall inflation. Some believe this is still the case today. But it isn’t.”

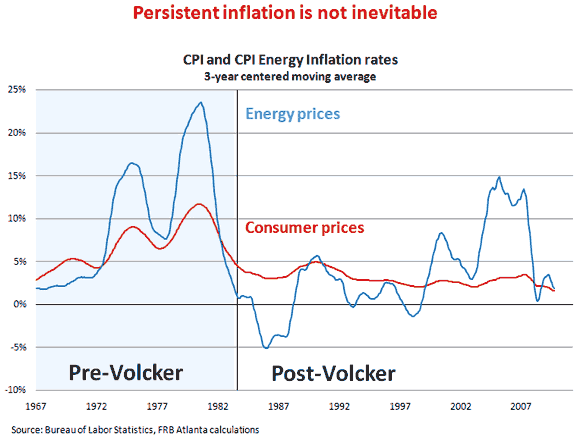

You can gain an appreciation of this point by looking at a simple chart of energy prices along with average annual inflation, over three-year periods.

As Meyer notes, energy prices tended to feed through to overall inflation in the low-credibility pre-Volcker years. They have not shown this tendency in the high-credibility post-Volcker years:

Note that I did not follow Meyer in making comparisons relative to core, but rather to actual realizations of overall inflation over three-year windows. The rationale for that type of comparison was explained this morning in a speech by Atlanta Fed president Dennis Lockhart:

“… contrary to popular opinion, Federal Reserve officials do actually eat and fill up their gas tanks. The FOMC’s mandate, as I see it, is to control the inflation rate we all experience—so-called headline inflation. In other words, I interpret the Fed’s price stability mandate as requiring the FOMC to manage the growth rate in the average of all prices, including food and energy.

“… it’s our job to control that headline inflation over the course of time. It’s not feasible to exert such control day-to-day or month-to-month or even quarter-to-quarter. But monetary policy can control the rate of overall inflation over the medium term. In operational terms, I think growth in overall consumer prices around 2 percent per year through a period shorter than the proverbial ‘long term,’ say, a medium-term period of three or four years, is consistent with the Fed’s price stability mandate.”

Though I do not, in any measure, disagree with Meyer’s assertion that core inflation measures are really our best indicators of the underlying inflation trend, President Lockhart acknowledges our understanding here that the proof is in the pudding:

“… like my colleagues on the FOMC, I continuously monitor performance against our price stability objective. This involves monitoring not just inflation today but importantly the course of inflation expectations, whether derived from simple surveys or pulled from financial market prices. I am prepared to support a change of policy if evidence accumulates that the low and stable inflation objective is at risk.”

Hopefully, the ongoing effort for greater transparency and accountability—evidenced by the new press conferences and remarks like those from President Lockhart—will mitigate the risks to “the low and stable inflation objective” and make future editions of the chart above look more like the second half than the first half.

Leave a Reply