The spectacular drop in oil prices means that inflation is going to fall even further below the Fed’s 2% target. Does that raise any new risks for the economy? I say no, and here’s why.

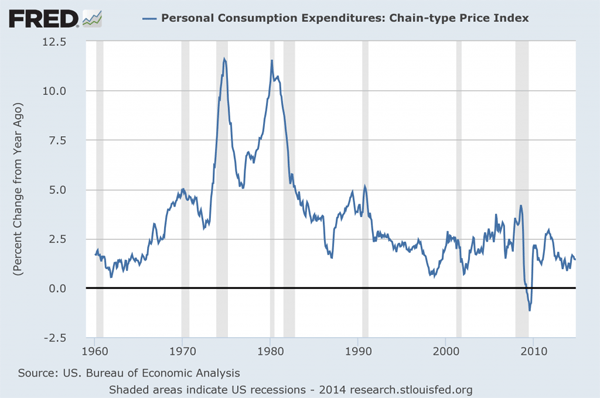

Year-over-year percent change in the monthly deflator for personal consumption expenditures. Source: FRED.

In economists’ theoretical models, inflation usually is often thought of as a condition in which all wages and prices move up together by the same amount. For a given nominal interest rate, the lower inflation, the higher is the real cost of borrowing. With the short-term nominal interest rate still stuck at zero, a decrease in inflation could discourage spending, something the Fed would rather not see happen in the current situation. Or so the theory goes.

But typical consumers often have something very different in mind when they talk about inflation. Many people think of inflation as a condition where the cost of the goods and services they buy goes up but their wages do not. Not so surprising then that while the Fed says it wants more inflation, most consumers say they do not.

What’s happened to oil prices this fall looks more like the average Joe’s version of reality than the Fed’s. The average U.S. retail price of gasoline right now is about $2.40 a gallon. Last year American consumers and businesses bought 135 billion gallons of gasoline at an average price of $3.60 a gallon. If gasoline prices stay where they are and if we buy the same number of gallons of gasoline this year as last, that leaves us with an additional $160 billion to spend over the course of the year on other items. If we restate the total savings for U.S. consumers and businesses in terms of the 116 million U.S. households, that works out to almost $1400 per household.

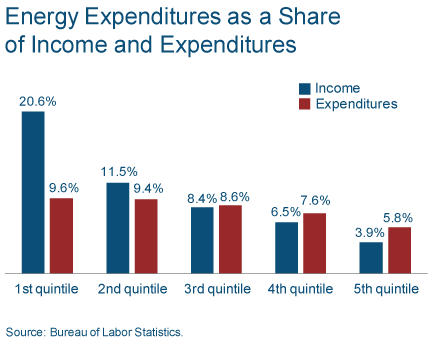

It’s a particularly big deal for the lower-income households, who spend a much higher fraction of their income on energy.

Source: Daniel Carroll.

Historically consumers have responded to windfalls like this by becoming more open to the big-ticket purchases that play a huge role in cyclical economic swings.

So no, any deflation associated with the gasoline price drop is not going to discourage aggregate demand. What it does do, however, is give the Fed a little more time to be patient before it needs to worry about raising interest rates.

Low oil prices are good for business.