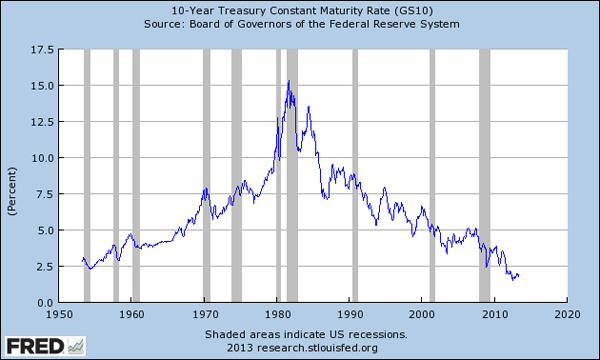

The yield on 10-year U.S. Treasury securities averaged 1.8% during 2012, the lowest levels in 60 years. But that episode may now be behind us.

Interest rate on 10-year Treasury security, April 1953 to May 2013. Source: FRED.

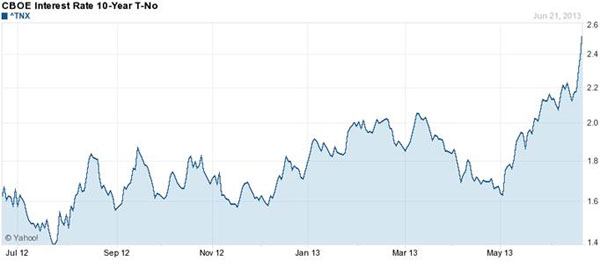

The yield closed Friday above 2.5%, with half the gain from last year’s levels coming during the last week alone.

Interest rate on 10-year Treasury security inferred from CBOE TNX, June 2012 through June 21, 2013. Source: Yahoo Finance.

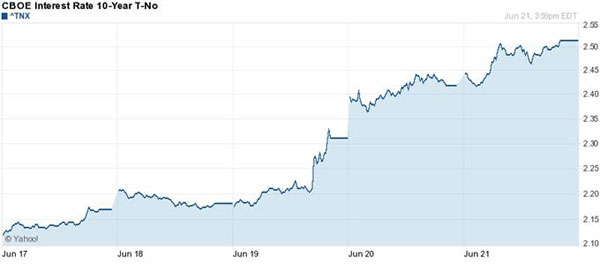

About 10 basis points of the increase came in two sharp jumps on Wednesday. The first began around 2:00 p.m. EDT with the release of the minutes of the latest FOMC meeting, and the second around 2:42 p.m.

Interest rate on 10-year Treasury security inferred from CBOE TNX, June 17, 2013 through June 21, 2013. Source: Yahoo Finance.

That second jump on Wednesday appears to coincide with the statement by Fed Chair Ben Bernanke in a press conference that Fed bond purchases might end when the unemployment rate reaches 7%:

If the incoming data are broadly consistent with this forecast, the Committee currently anticipates that it would be appropriate to moderate the monthly pace of purchases later this year; and if the subsequent data remain broadly aligned with our current expectations for the economy, we would continue to reduce the pace of purchases in measured steps through the first half of next year, ending purchases around midyear. In this scenario, when asset purchases ultimately come to an end, the unemployment rate would likely be in the vicinity of 7 percent, with solid economic growth supporting further job gains, a substantial improvement from the 8.1 percent unemployment rate that prevailed when the Committee announced this program.

As Bernanke emphasized, the forecasts of FOMC members anticipate that the unemployment rate might be 7.2-7.3% by the fourth quarter of this year. The Survey of Professional Forecasters expects unemployment to still be at 7.2% by the second quarter of 2014. Bill McBride provides a careful analysis of when the Fed’s stated objectives for GDP, unemployment, and inflation are likely to be attained, and concludes

It is possible that the FOMC could start to taper QE3 purchases in December, but it would take a pickup in the economy. (September tapering is less likely, but not impossible– but the pickup would have to be significant).

If anything, the Fed statements seem to push back the date of tapering. The baseline assumption in my paper with Greenlaw, Hooper and Mishkin written in February was that Fed purchases would continue at their current pace through the end of 2013. For a while, I had been thinking the Fed could move earlier than that. But based on the latest FOMC statements, it looks like it could well be even later.

Of course, if the economy does pick up more quickly than many are forecasting, tapering could begin earlier. But, as I noted last week, those are the same conditions under which interest rates would likely rise even if the Fed does not change its bond purchases.

Mention by the Fed of a 7% unemployment figure seems mainly to be conveying that the Fed has actively and concretely discussed the conditions under which the bond-buying will end. If you assumed they never would, then I guess this comes as news.

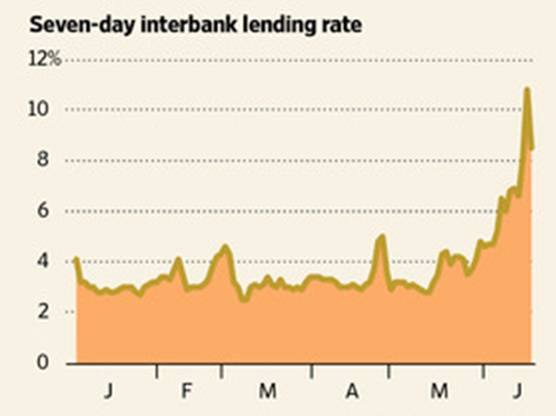

But it’s interesting to note from the last figure above that another 20 basis points came on Thursday and Friday. You can’t attribute this to revised anticipations that the economy is going to strengthen even sooner than the Fed is predicting. In fact, the news coming Wednesday night U.S. east coast time and Thursday morning in Asia was rather troubling. Interest rates on the Chinese interbank market have been rising sharply in conjunction with rising rates in the U.S. and a weakening Chinese economy.

Chinese interbank lending rate. Source: WSJ.

Part of what has been going on in China is complicated schemes under which enterprises borrow dollars cheap in the U.S. in order to finance loans in China. The prospect of rising U.S. rates seems to have produced a major shock for Chinese markets, the implications of which echoed back across the world on Thursday and Friday.

Interestingly, the borrowing side of the Chinese carry trade is based on low short-term U.S. rates, and the Fed is trying hard to communicate that increases in the short-term rate are even farther away than any tapering of its long-term bond purchases. But the mechanics of the carry trade as described by Izabella Kaminska sound rather bubbly, in which the players have convinced themselves that they’ll be smart enough to get out before everyone else. In that kind of environment, announcements like those Wednesday from the Fed can end up being a major event.

The Fed of course would like to see credit extension go to sectors like the U.S. housing market, and this certainly has been happening as well. But events outside the U.S. last week make it clear that managing the unconventional policy tools on which the Fed has recently been relying can be a tricky business, both going in and coming out.

Which seems all the more reason that, when the U.S. unemployment rate does get down to 7%, the Fed would like to be out of the business of buying long-term securities to the tune of $85 B a month.

The question at the moment is how long it is going to take before that happens.

Leave a Reply