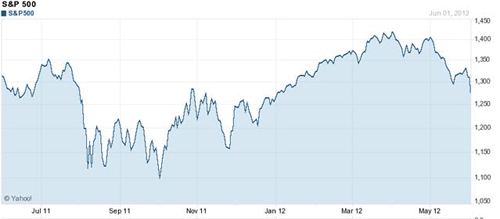

May was a bad month for U.S. stocks. June started out worse, with the S&P500 on Friday down 9% from where it stood at the beginning of May. That puts us back about where we started the year in January, though still significantly above last fall’s lows.

S&P500 U.S. stock price index. Source: Yahoo Finance.

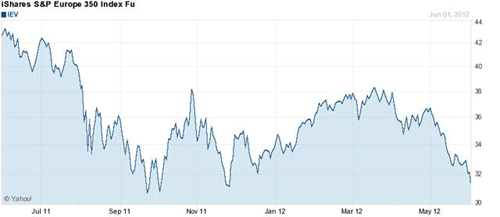

This marks the third time over the last 12 months that we’ve seen close to 10% declines in stock prices within the space of a month. The first was associated with the U.S. debt ceiling debacle last summer, and the second with concerns last fall that European sovereign debt problems would spill over into other European countries. This time Europe again appears to be ground zero.

iShares S&P350 Europe stock price index. Source: Yahoo Finance.

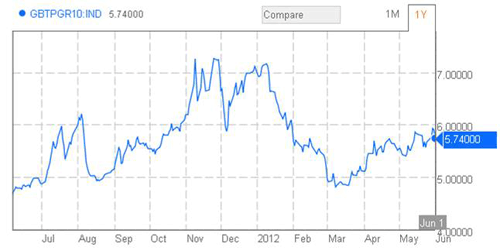

In November, one big concern had been Italy, with the government’s borrowing rate spiking above an unsustainable 7% rate. That rate has been climbing back up since March, but is still below 6%.

Yield on 10-year Italian government bonds. Source: Bloomberg.

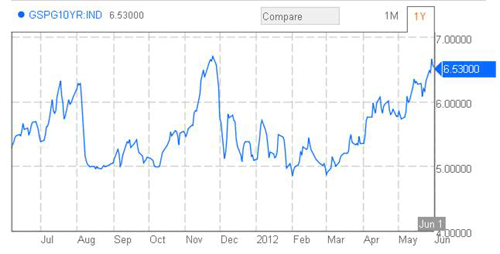

But now Spain, another very important European economy, is again being asked to pay yields very close to the highs last November.

Yield on 10-year Spanish government bonds. Source: Bloomberg.

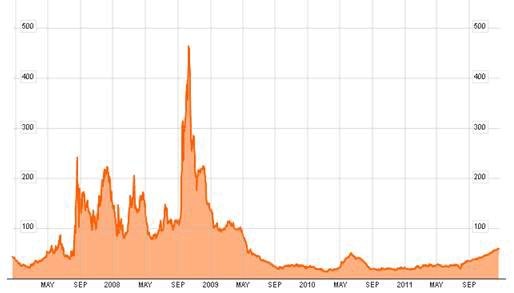

The immediate problems last fall were mitigated by the European Central Bank’s Long-Term Refinancing Operation, which allowed European banks to borrow up to 3 years from the ECB at a 1% interest rate, and which would enable the banks, if they chose, to take on more of the sovereign debt. The program has been successful in keeping short-term lending rates between European banks modest, as indicated for example by the TED spread, which is the gap between the 3-month interbank borrowing rate on Eurodollars and the 3-month U.S. T-bill rate.

Source: Bloomberg.

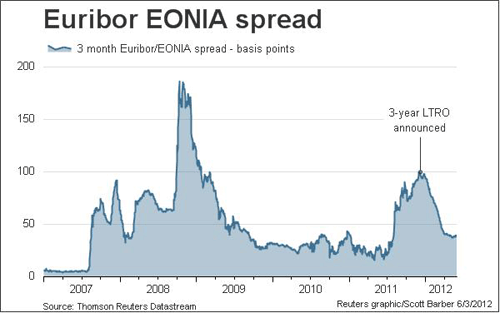

The spread between the 3-month and overnight euro borrowing rates also remains moderate.

Source: Thomson Reuters.

But as Calculated Risk observed in mid April:

The ECB’s LTRO has bought a little bit of time, but if the policymakers stay focused on austerity, they will fail. A key European analyst pointed out last week that essentially all recent sovereign issuance in the periphery has been purchased by in-country banks, and that was related to the LTRO from the ECB. In other words, there is no private market for peripheral sovereign debt. The key analyst concluded: “The EMU (Economic and Monetary Union) is over”.

And if it is over, what does that mean? Dropping out of the euro among other things requires some kind of terms for settlement of contracts, with one possibility being you’re repaid in “Greek euros” no longer trading at par with the major currency. People who lend short-term in euros– whether they are major financial institutions or small-time depositors– may be hesitant to do so when there are doubts about the country remaining in the monetary union. We’re already seeing not a bank run but what PIMCO’s Mohamed El-Erian calls a slower “jog” as depositors take their money out of banks in Greece and Spain. Much of Europe is already in a recession, and significant financial disruptions there would hardly leave the U.S. or emerging economies unscathed.

World Bank President Robert Zoellick thinks that this summer is looking like an eerie echo of the months leading up to the Lehman bankruptcy in September 2008, this time with European sovereign debt taking the role of mortgage-backed securities as the asset no longer viewed as safe. But one important difference is that this time the banks are swimming in liquidity. A TED spread at 40 basis points does not look remotely like an echo of early 2008.

TED spread, December 2008 to December 2011. Source: Econbrowser.

I guess we’ll find out how much difference that makes.

Leave a Reply