Here’s another article showing the efficiency of markets:

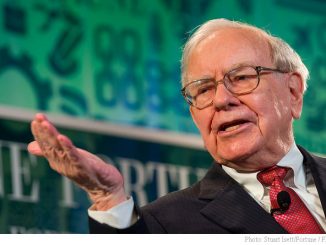

Warren Buffett made a friendly bet four years ago that funds that invest in hedge funds for their clients couldn’t beat the stock market over a decade. So far he’s winning.

The 81-year-old Buffett, who is chairman of the holding company Berkshire Hathaway Inc. (BRK/A), ended last year neck and neck with the Protégé funds as the Vanguard fund climbed by 2.1 percent and the Protégé hedge funds lost an estimated 3.75 percent.

The first two months of this year pushed the Vanguard fund ahead as stocks returned 9 percent, more than twice the gains of hedge funds.

If you do the math the performance gap is around 10%, even larger than four years of the 1.25% annual expense ratio for mutual funds that invest in hedge funds. They’d have been better off throwing darts.

But before Buffett gets too cocky, he might want to consider the final sentence of the article:

Berkshire Hathaway shares have slumped almost 17 percent since the end of 2007.

Ouch! Three years ago I argued that even if markets were perfectly efficient, they would look inefficient. That’s because for every 1,000,000 investors you’d expect one guy to outperform the market for 20 consecutive years. The masses would call that lucky guy a genius, even if he was just an average bloke from Nebraska.

I predicted that after the lucky guy became the richest investor on Wall Street, his returns would no longer look so impressive. So far I appear to be right. That doesn’t mean the EMH is precisely true (it’s not), but I’m having more and more trouble finding any useful anti-EMH models for investors.

And while we are at it, how about those bearish stock market comments by Nouriel Roubini in May 2009? And why wasn’t Robert Shiller screaming “buy” in March 2009?” One by one all the anti-EMH arguments that have been thrown at me seem to be melting away. The EMH is widely ridiculed, but will outlive all its critics.

PS. In fairness to the other side, I did a post bashing Keynes as an investor about a year ago. It now looks like his decisions managing the Cambridge University endowment were substantially better than those managing his personal investments. Oddly, he wasn’t able to market time, rather he was a successful stock-picker. One would expect a macroeconomist to win through market timing, if they had any advantage at all.

Leave a Reply