The short summary: The Chinese policy of buying dollars can be best understood as an indirect purchase of U.S. knowledge capital–technology and business know-how. That, in a nutshell, is why we feel poorer today. Unless the Obama Administration understands the link between the undervalued yuan and the global flows of knowledge capital, negotiations with China are doomed to fail.

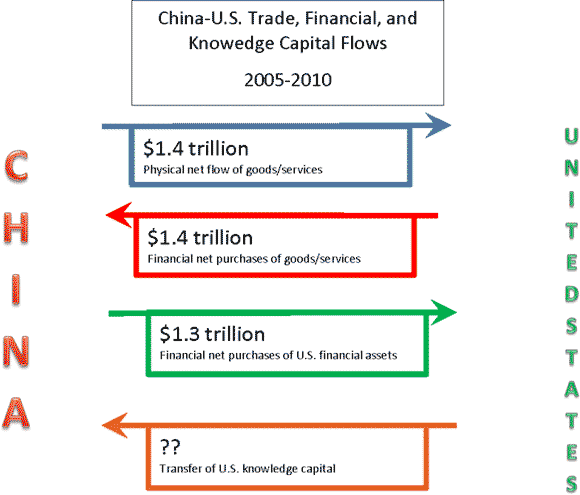

Viewed in the usual economic light, Chinese exchange rate policy in recent years looks like a gift to the U.S.. By buying up dollars to keep the yuan low, China–still a poor country– is effectively lending money to the U.S.–still a rich country–to buy Chinese products. According to the official statistics, the U.S. has run a cumulative $1.4 trillion trade deficit with China since 2005. But over the same period, Chinese ownership of dollar-denominated financial assets in the U.S. has risen by $1.3 trillion.

To put it another way, the conventional statistics seem to be saying that the U.S. is getting $350+ billion a year in cheap clothing, electronics products, and toys at no real cost today. What’s not to like?

But if this explanation was really correct–if that purchase of dollars was a gift from China–the U.S. would be feeling happy and prosperous right now. We have received all of these cheap goods and services, without having to give up very many of our own resources.

But of course, the U.S. doesn’t feel rich and happy right now–we feel poorer, while the Chinese are feeling more prosperous. How can we explain this?

The reason why the Chinese purchase of dollars seems like a gift is because we have a 20th century statistical system trying to track a 21st century global economy. We can do a decent job tracking the flows of goods and services and a passable job tracking financial flows. But there is no statistical agency tracking global knowledge capital flows–and that’s where the real story is. Take a look at this diagram.

The first three boxes represent the conventional view: The U.S. gets cheap goods and services, and then pays for them by selling financial assets.

But that leaves out the the transfer of knowledge capital from the U.S. to China. In effect, the Chinese purchase of dollars is a mammoth subsidy for the transfer of technology and business-know into China.

Consider this. When China keeps the yuan low, that’s an inducement for U.S.-based companies to set up factories and research facilities in China, both for sale in China and for imports back to the U.S. . And that, in turn, requires a transfer of technology and business know-how from the U.S. to China.

My favorite example is furniture makers. Over the years, U.S. furniture makers had accumulated this vast storehouse of knowledge–for example, how to make coatings on dining room tables that are less likely to chip or discolor from heat or liquids. That’s one of the differences between a low-quality and a high-quality table.

As the manufacturing of furniture was offshored to China, the knowledge capital had to be transferred as well. And that, in turn, helped turn the Chinese furniture industry into a global exporting powerhouse.

Now, let’s stop and make three points here. First, we need to compliment China. It is not easy to absorb knowledge capital from the outside and make good use of it. Frankly, all sorts of other countries could have tried the same exchange rate trick, and it wouldn’t have worked for them.

Second, the transfer of knowledge capital to China doesn’t mean that the same knowledge capital disappears in the U.S. However, our knowledge capital does become less valuable because there is more global competition–and that’s why we feel poorer.

Third, what’s needed from Washington is a sophisticated response that both focuses on rebuilding our own knowledge capital, while at the same time slowing down the exchange-rate knowledge capital pump. More to come on this.

Leave a Reply