What’s holding back the U.S. labor market? Why does employment growth remain slow? Why does the unemployment rate remain so persistently high? Is a prolonged jobless recovery possible? These questions are naturally at the forefront of current policy debates.

Some economists believe–were trained to believe, I would say–that the lacklustre performance of the labor market is easy to explain: there is a lack of demand. Just ask firms why they’re not hiring: a lack of product demand frequently tops the list reasons provided.

I’m not sure that economists can rely on answers like this to identify the type of aggregate shock that is afflicting the economy. Think about the original multisector real business cycle model of Long and Plosser (JPE 1983). A negative productivity shock to one sector in their model economy could lead to a decline in the production and employment in many sectors of the economy. This is because firm level production functions use the intermediate goods of many sectors as inputs into their own production processes. To an individual producer, it would appear as the demand for his product is declining. And he would be correct. This lack of demand, however, bears no relation to the concept of “deficient demand” in the Keynesian sense.

In any case, let us take this deficient demand hypothesis seriously for the moment. Then I want to ask how this hypothesis might be reconciled with the labor market data I present below.

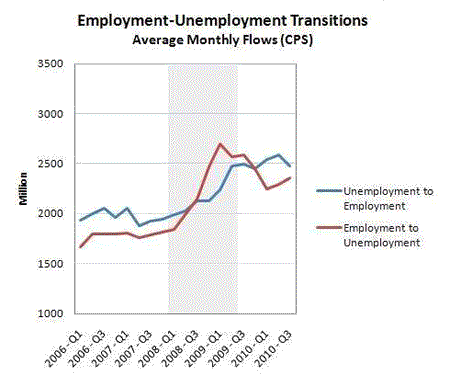

The first diagram plots the average monthly flow of workers between employment and unemployment (all data is from the U.S. Current Population Survey). The red line plots the EU flow (the flow of workers who made a transition from employment to unemployment). Leading up to the recession (shaded area), we see that in a typical quarter, roughly 1,750,000 workers per month exited employment into unemployment.

The blue line plots the UE flow (the flow of workers who made a transition from unemployment to employment). Leading up to the recession, we see that in a typical quarter, roughly 2,000,000 workers per month exited unemployment into employment.

When the recession hits, there is a large upward spike in the EU flow, as one would expect (people losing their jobs and becoming unemployed). This part seems consistent with the deficient demand hypothesis. However, look at what happens to the UE flow. While it does not rise as sharply as the EU flow, it rises nevertheless…and continues to remain high even as the EU flow declines. Is this surge in job finding rates among the unemployed consistent with the deficient demand hypothesis?

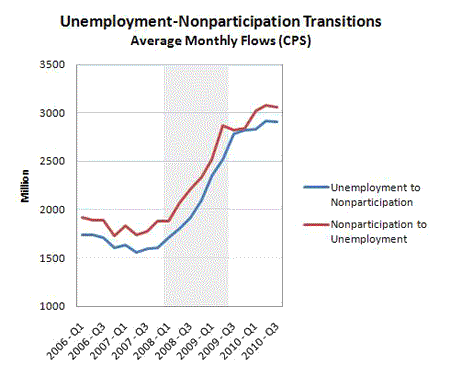

The next diagram plots the transitions between unemployment and nonparticipation (not in the labor force). The blue line denotes the UN flow (the flow of workers from unemployment to nonparticipation) and the red line denotes the NU flow (the flow of workers from nonparticipation to unemployment).

As you can see, these monthly flows are huge. And as one might expect, the UN flow rises dramatically during the recession. These are “discouraged workers;” and the phenomenon seems consistent with the deficient demand hypothesis.

But again, the surge in discouraged workers appears to be more than offset by a surge in “encouraged workers.” How is this consistent with the deficient demand hypothesis?

It seems to me that this sort of data appears to be more consistent with an increase in reallocative activities in the labor market, rather than deficient demand. But maybe not. And if not, then I am curious to know what sort of stories people might tell to square their pet hypothesis with the data above.

Leave a Reply