In a recent blog post, I explained that government deficits increase the private sector’s holding of net financial assets. And this led to the following question from one reader:

“How does a chartalist respond to the idea that gov’t spending does not actually add $ to the private economy because of debt issuance?”

And to the following command from another:

“stop insisting that gov’t deficits add wealth to the private sector (they don’t if the gov’t sells debt).”

Apparently, both readers believe that budget deficits could, in theory, increase the private sector’s holding of net financial assets, but that, in practice, they do not because, the sale of bonds “pulls dollars out of the private economy,” leaving the private sector with no net addition to their holding of financial assets.

Below, I show why this is wrong. And note that I am showing that it is wrong. I am not cutting any corners, committing any economic sleight of hand or glossing over any institutional detail. I’m tracing through the actual balance sheet entries that reflect the government’s fiscal operations.

Before we begin, let’s make sure we understand what actually happens when the Treasury issues debt in anticipation of running a deficit. In the U.S. this involves a debt auction. So let’s suppose that the Treasury plans to spend $100 and anticipates tax payments in the amount of $90. If it did not sell bonds to coordinate its fiscal operations, the private sector would end up with a $10 net addition to its financial holdings. On this point, there appears to be general agreement. But what happens when the Treasury auctions off $10 of new debt in order to offset the “reserve add” that would otherwise result from this deficit spending?

This involves the use of what are known as Treasury Tax & Loan Accounts (TT&L). These accounts are held by thousands of private banks – known as Special Depositories – across the country. When one of these banks wishes to purchase government debt, it acquires the debt (Treasury bonds) by crediting the Treasury’s TT&L account. (Note that this is exactly how a commercial banks acquires a loan – i.e. it credits the bank account of the borrower and adds the loan to its books.)

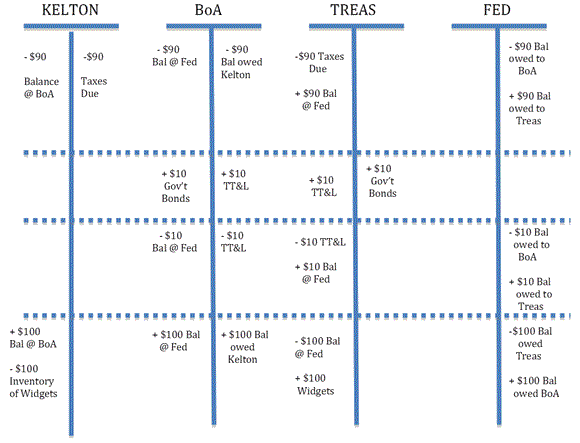

Now, back to my example. Let’s break the entire process down into four distinct stages so that we can see what’s happening to the balance sheets of the relevant players at each step of the way. (Note: Stages are separated by dashed lines, beginning with stage 1 at the top.) For simplicity, let’s assume that I am the only taxpayer (and also the only non-bank producer) in the economy, so I’ll foot the entire tax bill, T = $90. The government will spend $100 buying whatever it is that I produce (economists seem to like widgets, whatever those are), and I’ll deposit any payments I receive into Bank of America (BoA).

In stage 1, I settle my tax obligation with the state by writing a check for $90 on my account at BoA. My assets are reduced by $90 (I have less money in my account), and my liabilities are reduced by the same amount (I no longer owe the government $90). As a result of this payment, my bank marks down the size of my account, and it experiences an equivalent decline its reserve account at the Fed. The Treasury, meanwhile, gets a credit to its bank account, which is held with the Fed, and it loses an asset (in essence, an accounts receivable) because it no longer has a claim on my income. The Fed’s balance sheet reflects the fact that the $90 payment is now in the Treasury’s account (and not Bank of America’s).

In stage 2, the Treasury sells $10 of debt to BoA, and BoA pays for these bonds by crediting the Treasury’s TT&L account. (Again, this is analogous to a bank acquiring a loan by crediting the borrower’s account.) It does not “cost” the bank anything. No existing resources (reserves) are spent when the bond is acquired. BoA gets the bonds (assets) and the Treasury gets a credit to its account at BoA.

In anticipation of its imminent spending, the Treasury places a “call” on its TT&L account. This is a formal direction that instructs BoA to transfer funds from its TT&L account to the Treasury’s account at the Fed. This is shown in stage 3. Because the Treasury is moving its account out of BoA, BoA experiences a loss of reserves. The Fed changes its balance sheet to indicate that the Treasury has added $10 to its account at the Fed, and BoA has lost $10 in its reserve account.

Finally, in stage 4, the government buys $100 of widgets from me, and it pays for them by writing a check on its account at the Fed. I deposit the check into my account at BoA, BoA gets an equivalent credit to its reserve account at the Fed, the Treasury’s balance is reduced by $100, and the Fed’s balance sheet reflects the fact that it owes the Treasury $100 less and BoA $100 more.

Whew! So where does all of this leave the private sector? My bank account has an additional $10 in it (my asset), which is offset by the fact that BoA owes me an additional $10 (their liability). This nets to zero. But, wait! There is still a new financial asset out there . . . the government bond! And this clearly shows that deficit spending, even when we account for the sale of government bonds, increases the private sector’s holding of net financial assets.

** One caveat: I did something here that adherents to MMT may wish I had not done – I began with the payment of taxes rather than with government spending. As we in the MMT tradition consistently insist, spending must, as a matter of logic, precede taxation in the first instance (for it would be impossible to collect dollars from the private sector unless they had first been spent into existence by the public sector). But in the real world, the Treasury receives tax payments on a daily basis, and government checks are clearing bank accounts on a daily basis as well. So there is really no objective beginning point or ending point. You can begin with spending if you prefer. But it will not alter the result.

Leave a Reply