Over the last month, a consensus seems to have emerged that (1) the Fed has the ability to depress long-term yields further, and (2) the Fed has the intention to implement such measures. That raises the possibility that recent market moves represent a bet already placed by market participants on the basis of the logical implications of (1) and (2).

In the good old days of Fed watching, namely, back when the Fed actually had something obvious it could do, market participants became extremely skilled at anticipating the target that the Fed would choose for the fed funds rate well in advance of the FOMC decision and public announcement. When the actual FOMC announcement came, very little happened, because it had all been already priced into the market.

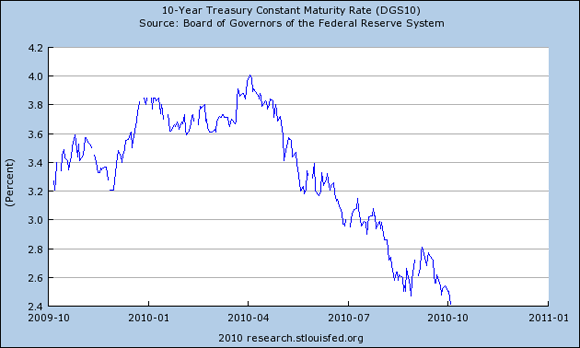

That game has been up since the end of 2008, when the Fed drove the fed funds rate essentially to zero. But if the Fed is now using very large-scale asset purchases to push around longer-term yields, should those operations warrant a new venue for Fed-guessing by bond markets? It’s certainly striking how much yields have declined as the conviction of a second round of quantitative easing (referred to by some as “QE2”) has grown. Over the last month, the 10-year yield has fallen 40 basis points. If you wanted to attribute all of this to expectations of QE2, and if you were assuming that $400 billion in long-term bond purchases could lower the rate about 13 basis points, you might think the market has already discounted some $1.2 trillion in additional large-scale asset purchases. All of which raises the interesting possibility that if the Fed were to announce in November another trillion in purchases, nothing would happen, because the market has already discounted it.

Source: FRED

Another aspect of those “good old days” of monetary policy was that the Fed never needed to know the value of multipliers like this one in order to be able to implement the policy. The Fed would simply announce its target for the fed funds rate, and the market would jump there instantly, because it knew that the Trading Desk of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York stood ready to add or remove reserves as needed to maintain the target. The Fed had a big enough stick that all it had to do was to say what it wanted, and so it would be. Indeed, in the years before the Fed started publicly announcing its target in 1994, something very similar happened. If the Fed added reserves at a time when fed funds were trading a little below a new target, savvy market participants would figure out that the Fed was aiming for a lower target than before, and that in itself was enough to bring the rate down.

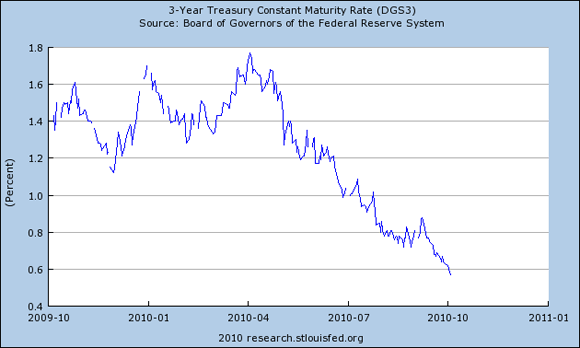

If the Fed were to aim, explicitly or implicitly, for a target for a longer-term interest rate, what would it pick? Presumably it wouldn’t be a 10-year rate, but something more intermediate like a 2- or 3-year rate. These of course are already quite low, and have plunged along with longer yields the last month. Joseph Gagnon suggests that the Fed aim for 25 basis points on the 3-year yield, as one way of being very precise (and aggressive) about what it means by keeping rates low for an extended period.

Source: FRED

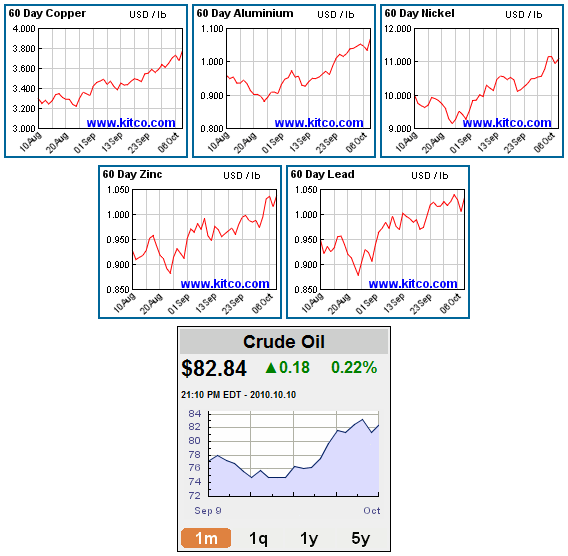

Of course, the growing market belief that QE2 is coming is itself a response to growing evidence of economic weakness. That economic weakness would also by itself be a factor that could lower bond yields, regardless of what the Fed is planning to do. But it’s curious that we’ve also seen commodity prices taking off at the same time interest rates are coming down. While a weakening economy makes sense as an explanation for falling bond yields, it does not make sense as an explanation for rising commodity prices. But a growing market conviction that QE2 is coming could be consistent with both.

Even so, I have a hard time fully reconciling the recent behavior of bond and commodity markets. It’s true that while the 10-year yield is down 40 basis points since September 10, 10-year TIPS are down 50 basis points, consistent with the view that there may have been a modest decrease in real rates and increase in inflationary expectations. That of course is exactly what QE2 is supposed to accomplish. But I’m doubtful that such a modest effect could be reconciled with the 10% moves in commodity prices we’ve seen over the same period. The people who think that 10-year nominal bonds paying 2.4% are a good buy, and who think that copper at $3.80 a pound is a good inflation hedge, can’t both be right.

I continue to believe that the Fed needs to watch commodity prices carefully as an indicator of how far to push on its new-found accelerator pedal. It may be that, as far as the market is concerned, QE2 has already happened, and it’s already accomplished all it could.

Leave a Reply