Warren Buffett thinks the U.S. is still in a recession, declaring in a CNBC interview last week:

I think we’re in a recession until real per capita GDP gets back up to where it was before. That is not the way the National Bureau of Economic Research measures it. But I will tell you that to any– on any common-sense definition, the average American is below where he was before, or his family, in terms of real income, GDP.

I don’t presume to be able to tell Warren Buffett what investment strategies work best. But I can provide some clarity on how economists use the term “recession,” and hopefully shed some light on the issue that Buffett and others have raised.

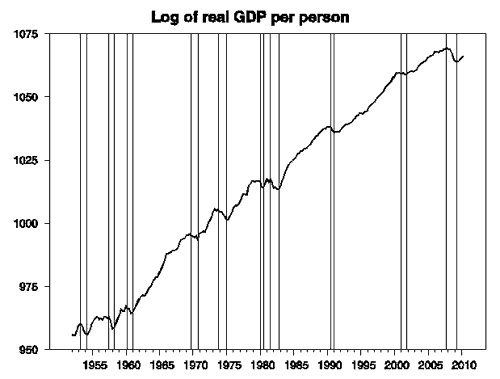

At least since the work of Wesley Mitchell nearly a century ago, economists have characterized particular historical episodes in terms of the dates at which economic activity reached a peak before entering a period of decline. The low point on the way down is designated as a trough, and the episode between the peak and the trough is described as an economic recession. Here is a graph of Buffett’s preferred measure, real GDP per person. It is plotted on a logarithmic scale, so that a move up or down of 10 units on the vertical axis corresponds approximately to a 10% change in real GDP per capita. The NBER dates for business cycle peaks and troughs are indicated with vertical lines on the graph.

One hundred times the natural logarithm of U.S. real GDP per person, 1952:Q1 to 2010:Q2.

According to the traditional chronology, the recession ends when the economy starts growing again, not when it has grown so much that indicators such as real GDP per person are back to making new all-time highs. As a matter of arithmetic, the latter standard would always give you a later date than the true low point for economic activity, and a substantially later date in the case of a downturn as deep and recovery as sluggish as the one we’ve just experienced.

Economists have used the term “recession” to have this particular meaning– the episode between a peak and trough– for 150 years or so of data. Are Warren Buffett and the common-sense Americans on whose behalf he claims to speak within their rights to suggest that we have been using the term inappropriately? I would say that they’re very much justified in having an opinion on this, because the events that economists label as recessions are universally understood to affect everyone’s lives. So it’s quite appropriate that everyone feels entitled to talk about what the word “recession” should mean on the basis of personal and direct experience. People know they’re still not back to where they were, and the data confirm that. But when economists say that the recession is over, there never was a claim that things were back to normal.

So in part it’s simply a semantic issue of how a particular term is defined. Economists use “recession” to refer to a narrowly defined event, whereas many people appropriately want to be able to talk instead about the consequences that linger as a painful aftermath of the event.

But I think there’s more than just a semantic issue involved here. The reason that economists say that the recession, as we use the term, has been over for more than a year is that conditions have been steadily improving rather than getting worse. True, conditions haven’t improved as much as we’d hoped and expected, and they haven’t improved enough to put us back where we had been before the recession. But nonetheless, conditions have been improving rather than getting worse for the last 15 months.

And that is an important statement of fact that can easily get missed in the popular discussion of these issues.

Leave a Reply