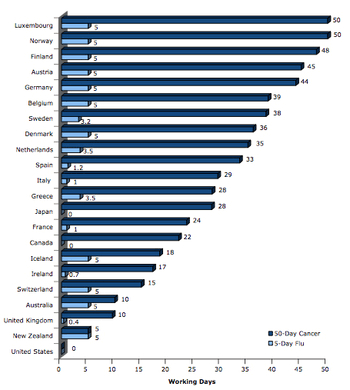

Ezra Klein is one of those bloggers, like Matt Yglesias or Andrew Sullivan, that sometimes make me want to just give up. Yesterday he started a new blog at the Washington Post, and promptly put up fifteen posts on his first day – and not the one line variety, either. Today, he brings us this chart from the Center for Economic and Policy Research:

This is Klein’s explanation:

You’re seeing two things here. The light blue line measures paid sick days. This is what you use if you need to take three days off because you have a fever. The dark blue line is paid sick leave. This is what you use if you need to take three months off because you have cancer. Every other country on the list offers at least one. Most offer both. The United States is alone in guaranteeing neither.

Why does this matter? Because sick people without paid sick days go to work anyway, infecting others and increasing the virulence of epidemics. Or, when it comes to things like the common cold, they simply get more people sick, which sucks for them.

As a father whose daughter is in her first year of pre-school, I’m more sensitive to this phenomenon than when I was younger. I’ve gotten sick at least five times this year – which is about five times more than normal – and I try to avoid going to my classes when I’m sick to avoid infecting other people (even though I’m paying about $100 per hour for those classes).

So why don’t we require paid sick days here in the United States? Of course, there’s always an ideological argument – that’s government intrusion into the private sphere – but the argument you hear more often is that it imposes costs on businesses, particularly small businesses. Well, what’s wrong with that? A government mandate would affect all companies equally, so it shouldn’t make it any harder to compete in general. For small business owners, it would take away the unpleasant choice between minimizing costs and treating your employees right; the people hurt would be the ones who are willing to minimize costs on the backs of their employees, and the ones helped would be the ones who are not. (For the record, my company has paid sick days – but we’re in an industry that generally treats its employees well, so I’m not claiming any particular virtue.) Put another way, it takes away the competitive advantage of employers who do not treat their employees well. For anyone worried about American competitiveness overall, look back at that chart.

But then the higher costs of paid sick days would be passed on to consumers, just like a tax, which would reduce consumption and represent a drag on the economy, just like any other tax. Yes – but this is just a question of externalities. We already pay that tax, just in different forms. We pay it in the health care costs of treating the sick; we pay it in shortened lifespans of people who die (in extreme cases) from contagious illnesses; we pay it in reduced quality of life due to being sick; and we pay it in parents staying home from work (paid or unpaid) to take care of children too sick to go to school or day care.

The difference is that in a free market, when you let each company decide not to have paid sick days, that company only internalizes a fraction of these costs: the fraction associated with lower productivity of its own infected employees, and possibly with the premiums of its health care plan – but many of these companies don’t have health care plans anyway. So, like with all externalities, if the firm doesn’t face the full costs of its production, you get too much of the thing it produces – in this case, sickness

Leave a Reply