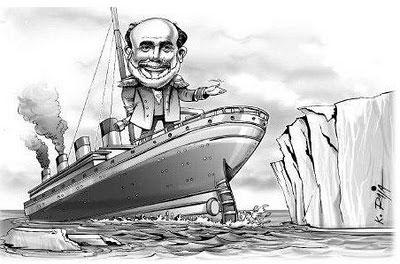

From 1987 when Greenspan took over the Fed until 2009 when the US hit Peak Debt, the US private sector added $34T of debt while US GDP only went up by $9T. Rather than seeing this as a classic Ponzi Scheme, economists praised it as financial innovation. Steve Keen, an economist out of Australia, writes a trenchant essay on this topic entitled What Bernanke Doesn’t Understand About Deflation that explains why this Ponzi Scheme is the greatest failure of the Fed and central banks around the world.

From 1987 when Greenspan took over the Fed until 2009 when the US hit Peak Debt, the US private sector added $34T of debt while US GDP only went up by $9T. Rather than seeing this as a classic Ponzi Scheme, economists praised it as financial innovation. Steve Keen, an economist out of Australia, writes a trenchant essay on this topic entitled What Bernanke Doesn’t Understand About Deflation that explains why this Ponzi Scheme is the greatest failure of the Fed and central banks around the world.

His point can be understood this way: what an economy produces (GDP) plus the increase in private debt equals the aggregate demand for stuff. The increase in debt ahead of GDP means the country is living beyond its means, consuming more than it produces. At some point this cannot go on, and the debt begins to shrink. As it shrinks, GDP less the change in private debt equals aggregate demand. As debt shrinks the drop literally sucks demand out of the economy.

- At the peak of our credit bubble, new debt drove US demand to an astounding $18T, $4T beyond GDP of $14T

- By 2010, the decrease in debt turned GDP of $14T into demand of $12T – an absolutely brutal turnaround of -$6T in two years

From $18T to $12T in two years means a third of the wind got sucked out of the sails of the US economy. In 2010 alone demand is headed to a drop of 17% – about what happened in 1930.

The next two years (1931 and 1932) saw drops of 27% and 24%.

While our recent massive increase in govt debt cushioned our drop, it cannot overcome it, especially with State governments now facing a estimated $1T shortfall over the next three years, and political pressure rising against taking on any more massive Federal debt.

The same problem occurred in 1930-33: excess debt from the Roaring ’20s led to the depression. It is incorrectly believed that Hoover failed to stimulate. The increase in Federal debt in 1930 ($1.1B) was larger than the decrease in private debt (-$0.7B). The problem is that in the year before, 1929, the excess of new debt over GDP was much larger ($5.7B). The delta is what matters, and the drop of $6.4B (delta between +$5.7B and -$0.7B) overwhelmed govt stimulus. The debt write-offs got larger over the next three years as the excess of the ’20s had to be worked off. It was only around 1934 that the horrific debt write-offs had begun to abate, and the Federal stimulus had caught up. (Steve’s essay has data tables that show this.)

Our problem was set in motion over those years from 1987 to 2009 (Peak Debt), when the US went on a debt-fueled consumption bender. At some point, the piper has to be paid. The excess has to be worked off. The US lacks the productive earnings to pay off the excess debt, so it gets written down. We have years of this process still to go.

Steve opines on why this mistake was made, the mistake being the celebration of excessive debt as financial innovation: both Keynesianism and modern economics as taught today are based on a presumption of equilibrium that harkens back to neoclassical economics. In the 1930s the leading US economist, Irving Fisher, who had been a neoclassicist, abandoned the presumption of equilibrium and proffered his debt-deflation explanation for the Great Depression. Bernanke, our current-day student of the Great Depression, in his criticism of Fisher’s explanation describes his theory thusly:

Fisher envisioned a dynamic process in which falling asset and commodity prices created pressure on nominal debtors, forcing them into distress sales of assets, which in turn led to further price declines and financial difficulties.

This seems about right. Think of what is happening right now in real estate. Despite all the attempts to roll things forward or restart the housing markets, demand has fallen to the floor and defaults are increasing while housing prices continue to drop. Bernanke however goes on to say something which seems to completely miss the dynamic we are living through:

[D]ebt-deflation represented no more than a redistribution from one group (debtors) to another (creditors). Absent implausibly large differences in marginal spending propensities among the groups, it was suggested, pure redistributions should have no significant macroeconomic effects.

So he would say the collapse of housing in the US should have no significant macroeconomic effects? Somewhere Bernanke is making a huge mistaken presumption. His critique does not comport with the real world. Steve points the finger to Bernanke maintaining that presumption of equilibrium. In an irony of history, the presumption of equilibrium which Fisher abandoned has crept back into modern economic thinking. Steve’s conclusion is priceless:

We might not be in such a pickle now if economics had started to become more of a science and less of a religion by following Fisher’s lead, and abandoning key beliefs when reality made a mockery of them. But instead neoclassical economics completely rebuilt its belief system after the Great Depression, and here we are again, once more experiencing the disconnect between neoclassical beliefs and economic reality.

Leave a Reply