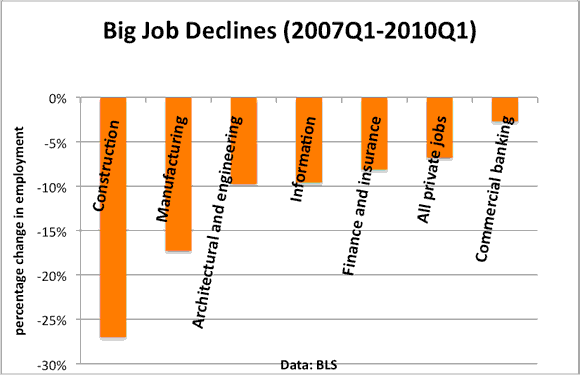

I’ve been watching the job numbers in financial services with some degree of surprise. Considering that the crisis was centered in the financial sector, it’s actually a bit odd that financial jobs didn’t do worse. Finance and insurance employment is down 8% over the past three years–but the real job crashes came in construction and manufacturing, down 27% and 17% respectively, not in finance.

Now, I can explain why construction went down. But manufacturing’s job loss would have been hard to predict.

Suppose that I took a time machine back to early 2007. I tell your 2007-self a recession is coming, and ask you to predict whether manufacturing or finance will have the deeper job decline, based on these three facts: (a) The U.S. will have the worst financial crisis in the last 80 years (b) Bear Stearns and Lehman will close their doors and (c) mortgage lending will dry up. I’m sure that very few of you would have expected manufacturing to have much bigger job losses than finance.

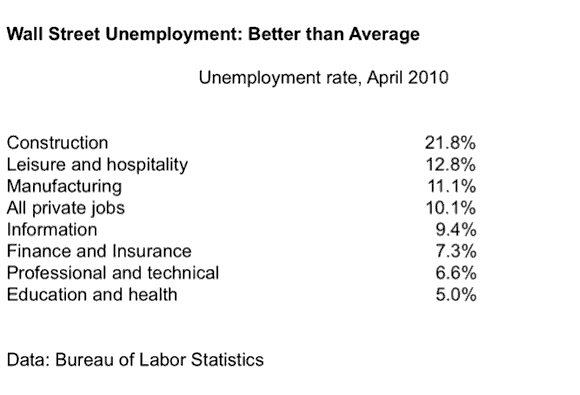

Equally odd, the unemployment rate in finance and insurance, at 7.3%, is substantially lower than the 10.1% for the economy as a whole. And yes, part of that reflects education, but that doesn’t explain why finance unemployment is substantially lower than the unemployment rate in the information sector, which is also a high-education sector.

And banks have started hiring again. JP Morgan CEO Jamie Dimon said a month ago that his bank plans to hire almost 9,000 new employees in the U.S. Citigroup, the most troubled of the large banks, basically kept its employment flat in the first quarter of 2010.

In addition, wages have been rising in the financial sector. Over the last year, hourly wages for all workers rose by 3% in financial services, roughly double the 1.6% gain for the economy as a whole. And let’s not forget the big profits reported by Wall Street banks for the first quarter.

What does this all mean? My theory is that as long as the U.S. is running a big trade deficit, financial sector jobs are going to do very well. The rest of the world has to lend large amounts of money to the U.S. to keep the global economy going, and all of that money has to be funnelled through Wall Street, which creats wel page jobs.

In some sense, Wall Street’s gain is proportional to Main Street’s pain. The big trade deficits means less production at home, but the deficits needs to be financed by debt–and any debt issuance, including U.S. Treasuries, ends up going through Wall Street.

Leave a Reply