For a few exciting minutes on Thursday, the Dow-Jones Industrial Average was down a thousand points, with some major stocks momentarily falling to a penny a share. The basic story appears to be as follows. Initial strong selling in some stocks such as Procter & Gamble (PG) led the New York Stock Exchange to halt trading temporarily in a few stocks until specialists could sort out what was going on. But trading in those stocks continued on other exchanges, where as a result of their thinner books, orders to sell at any price went far down the list of existing buy bids. These lower prices triggered further automatic selling that sent some stocks all the way through the list of outstanding bids until encountering basement bids at one cent a share.

One popular meme is to attribute these fireworks to the existence of multiple trading venues that didn’t all get shut down simultaneously (e.g., WSJ or NYT). But I think we should also be taking a closer look at the folks who were sending the sell orders rather than just blaming the exchanges for carrying out the instructions they received.

Let me frame my discussion of Thursday’s drama in terms of two very different views of what your strategy might be for investing in stocks. One view was articulated by John Maynard Keynes on page 156 of his General Theory:

professional investment may be likened to those newspaper competitions in which the competitors have to pick out the six prettiest faces from a hundred photographs, the prize being awarded to the competitor whose choice most nearly corresponds to the average preferences of the competitors as a whole; so that each competitor has to pick, not those faces which he himself finds prettiest, but those which he thinks likeliest to catch the fancy of the other competitors, all of whom are looking at the problem from the same point of view. It is not a case of choosing those which, to the best of one’s judgement, are really the prettiest, nor even those which average opinion genuinely thinks the prettiest. We have reached the third degree where we devote our intelligences to anticipating what average opinion expects the average opinion to be. And there are some, I believe, who practise the fourth, fifth and higher degrees.

Is there an alternative interpretation of what gives a stock value, apart from what others think that others think it might be worth? Most assuredly there is, and the easiest way to understand that value is to contemplate buying a stock with the intention of never selling it, simply passing it on to your heirs, and from them to their heirs. Is the asset, if used in this way, of any benefit to you? Sure is, because even if you never sell the stock, you and your heirs can expect to receive a dividend payment from the company four times a year as long as the company stays in business. Those dividend payments will grow if the company’s earnings grow over time. Even for a stagnant company that sells exactly the same number of units each year, in an inflationary world the dollar prices of those goods (and therefore the number of dollars you receive in dividend payments) should grow over time.

The average dividend yield on stocks in the S&P500 at the moment is about 1.8%. The yield on a 30-year Treasury Inflation Protected Security is also about 1.8%. On one dimension, with equal yields stocks might seem more attractive than TIPS, since nominal dividends will grow faster than inflation. On the other hand, stocks are much riskier, because nobody knows for sure exactly how big those future dividend payments are going to be.

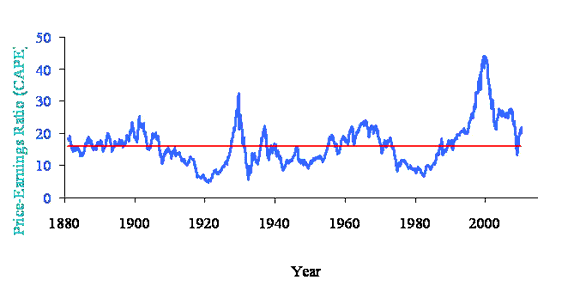

Historically, investors have demanded as risk compensation a significantly higher average real return from stocks relative to bonds than is reflected in the current equality of dividend and TIPS yields; the average dividend yield on stocks over the last 30 years was 2.8%. That means that if we return to average historical evaluations, stock prices would fall. I made this point from some related calculations last December. There I suggested that when Professor Robert Shiller’s long-term price-earnings ratio was above 20, it was time for caution. That ratio exceeded 22 at the April peak, but with last week’s correction is now just above 20. Here’s an update of the graph I discussed in December.

Blue line: Ratio of real value (in 2010 dollars) of S&P composite index to the arithmetic average value of real earnings over the previous decade, January 1880 to May 2010. Red line: historical average (16). Data source: Robert Shiller.

Whatever your stand on how to evaluate the tradeoff between risk and return, if you take the above perspective that the value of a stock ultimately derives from the stream of dividend payments that it delivers to its owner, then when the stock price goes down, it becomes a more attractive asset for you to buy, whereas when the stock price goes up, it is something you should consider selling.

But, you might ask, isn’t is possible that other people know more about those future dividend prospects than I do, so if they’re selling, maybe I should sell too? It’s not just possible that others know more than I do, it’s a certainty. But, let’s suppose that one minute ago I was persuaded that ahead of us was normal dividend growth, and the next minute something caused me to change my mind and believe that dividends were about to go through a meat grinder like we experienced during the Great Depression of the 1930s. As I showed in illustrative calculations in March of 2009, that Armageddon-level revelation would reduce the rational price I’d be willing to pay for most stocks, in the sense that I’ve been sketching here, by about 25%. The news that actually arrives on a given day would of course have a vastly more modest effect on how your calculation should come out. If overall stock prices fall 10% in the space of a few minutes, you can almost be certain that it’s not because anybody’s rationally-calculated fundamental valuations have declined by that amount.

Alternatively, you might argue, if stocks were 10% (or more) overvalued on Wednesday, as indeed I’ve just suggested that they may well have been, then couldn’t a dive of the magnitude we saw in the intraday excitement on Thursday be perfectly rational? Maybe so. But the Wednesday close and the Thursday intraday low price can’t both be rational– if one was right, then the other has to be wrong. More importantly, the time to make up your mind about that question is in the quiet of some Sunday afternoon, not when the crowd around you is suddenly panicking on a particular Thursday.

Let’s take a look at one of the amusing examples of trading on Thursday. Exelon (EXC) is a perfectly sound utility. The stock started and ended the day at about $42, yet at one point allegedly changed hands for a penny a share. If you are the owner of 100 shares of this stock on Wednesday May 12, the company will send you a dividend check for $55. They’ll send you another $55 (and likely eventually even more) every 3 months thereafter, as long as you own the stock. What rational person would possibly prefer to have $1 on Thursday May 6 in preference to owning 100 shares of the stock, say, for at least another week?

No sane person ever would. I wonder how many of the sell orders came not from actual humans, but instead from instructions programmed to execute automatically by computers. Anybody following such a strategy is obviously not a subscriber to my theory of fundamental value, but instead seems to be playing Keynes’ beauty contest game, having persuaded themselves, based on the historical correlations, that when the crowd starts to sell, if you can instruct your computer to sell at the “market price” faster than a human can even think, you’ll come out ahead.

Economists and financial engineers seem to approach stock markets differently. The financial engineers often see the game as figuring out whatever the historical predictability has been and trying to get ahead of it. Economists tend to ask what the equilibrium in the market would look like if everybody played the game the way the financial engineers do. The answer to that second question is, if momentum-chasing algorithms come to rule the financial world, those who try to follow them will be the biggest losers.

Another notion that’s popular with many financial gurus these days is the claim that you can eliminate certain risks to your portfolio with the right strategy of automatic trading and stop-loss sell orders. Again that claim invites an economic question– if you are getting an insurance policy, who is selling it to you? I believe the implicit answer is, you are counting on the market-maker to insure you by taking the other side of your escape transactions. But the curious thing about such an insurance policy is that the market-maker gets to decide what premium to charge you after you ask to collect on the policy. You just might find that the state of the world when you and your buddies all most desperately want to cash in on your insurance is exactly the time when the premium proves to be ruinously expensive.

Or if I haven’t persuaded you with these arguments, let me try a more modest suggestion– those of you whose computer programs sent an order to sell Exelon even if you only get a penny a share might want to consider tweaking the code just a bit.

And my advice for sane humans trying to deal with such a crazy market is this: as a first step, ignore all the other beauty-contest judges, and ask yourself whether the flow of future dividends you expect to receive by itself would be adequate compensation to you for your investment, given the risk associated with not knowing exactly what those dividends are going to be.

If it is, then allow yourself to relax as the computer programs written by the other contest judges try to devour each other.

If it’s not, then you’re in the wrong place at the wrong time.

Leave a Reply