The European Monetary Union is unprecedented, but the Eurozone Crisis is not. This column draws upon the experiences of previous banking crises, and compares the Eurozone Crisis countries. Like Japan before the 1992 crisis, Spain and Ireland had property bubbles fuelled by domestic credit. The Greek crisis is very distinct from crises in other Eurozone countries, so a one-size-fits-all policy would be inappropriate. The duration and severity of past crises suggest the road ahead will continue to be very rough.

As of July 2014, we continue to debate whether the European economy is out of the woods. The effectiveness of policies and the prospects of full recovery are under scrutiny. The unique nature of Europe’s monetary union begets further questions of whether policies should be designed to resolve a single euro crisis, or whether they should be designed to resolve multiple European crises occurring simultaneously. A discussion of whether the sui generis European project has led to a sui generis set of financial crises would provide a framework for these policy discussions.

There is an incredible wealth of information and experience that could shed light on these questions – financial crises are not new. Countries all over the world have experienced economic crises in the past, sharing similar vulnerabilities prior to the crisis. So past crises could guide us in designing policies in Europe. Yet each crisis comes as a surprise, with its own distinctive characteristics. The latest of these crises, the euro crisis, is no different.1 Its distinctive characteristics are twofold:

- First, the crisis started off with a global shock that led to synchronous crises.

- Second, the euro crisis is experienced by the European Monetary Union – a union that has no historical precedent.2

If so, then how much could we learn from past experiences?

The need for a different framework to compare crises

The existing literature studies whether on average the nature of crises change over time and/or across countries. Studies by Gupta et al. (2007), Rose and Spiegel (2010, 2011, 2012), and Frankel and Saravelos (2012) are among many that test for such differences making use of the ‘early warning system’ framework. While this framework allows for comparisons of crises on average, it does not allow the identification of case-specific information. The information about whether crises are different from each other on average hides possible divergences from average. On average, crisis behaviour could be sufficiently different across regions (or across time), yet two crises occurring in two different regions (or at two different time periods) could share sufficient similarities.

In order to identify such case-specific similarities, a tool that does not rely solely on the information regarding the relationship between averages but also takes into account individual specific information is needed. One such tool is the matching technique, which aims to statistically match similar observations and provide a way of clustering observations according to a set of pre-determined dimensions. In Sayek and Taskin (2014), we make use of the propensity score matching methodology to provide an alternative anatomy of the ongoing European financial crisis in light of this globally accumulated banking crisis experience.

In this propensity score matching exercise, the treated units are defined as the crisis episodes that occurred on or after 2007 – labelled as ‘new’ crises – and the control group as all the crisis episodes that occurred prior to 2007 – labelled as ‘old’ crises. Conditional on whether a country has been in a crisis at some point, the new crises are matched with the old crises. As such, the dataset used to carry out the matching exercise includes the 165 episodes of crisis (non-crisis episodes are not included in the dataset), where ‘being in a crisis currently’ is interpreted as a treatment.

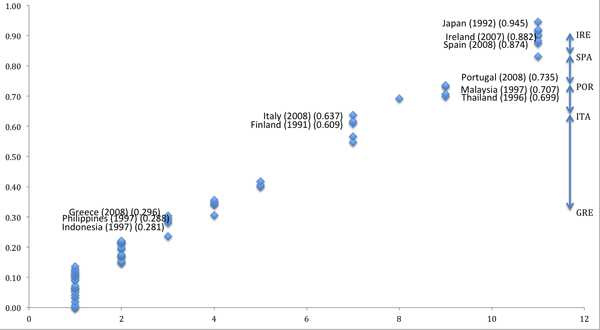

The current crisis episode is marked by its global nature and by occurring predominantly in high-income countries. The matching results suggest that these two characteristics of the recent crisis episode are quite distinctive – the current crisis shares no commonalities with past crises in either the dimensions defining the global economic environment or their national income or institutional qualities. However, despite these differences, the GIIPS economies share extensive commonalities in their respective pre-crisis domestic vulnerabilities with several past banking crisis experiences. Specifically, the euro periphery crises match mainly with crises of the 1990s, which are either among the big-five crises or the East Asian crises (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Radius matching

Echoes of past crises

The current-account imbalances and the evolution of private sector credit show significant similarities between the respective pre-crisis periods of the recent Portuguese crisis and the 1996–1997 Malaysia and Thailand crises. On the other hand, the build-up of the recent Irish and Spanish crises share with the 1992 Japanese crisis a property bubble that was fuelled by an exuberant domestic credit expansion. The unlikely match of the recent Italian case and the 1991 Finnish crisis seems to be mainly on account of the pre-crisis low levels of economic activity and the transmission of global slowdowns through international trade linkages. On the other hand, the match between the recent Greek crisis and the 1996–1997 crises of Indonesia and the Philippines bear significant similarities in their public sector debt patterns.

These matches also provide important information on how similar the GIIPS crises are among themselves. Findings suggest that the GIIPS crises encompass some very dissimilar crises as well as very similar ones. For example, the Spanish and Irish crises share a significant amount of similarities in their pre-crisis conditions, whereas the Greek crisis is very distinct from all other GIIPS crises. This finding is evidence against a one-size-fits-all policy prescription for the GIIPS countries. Therefore, the policy design of each country’s recovery should take into account the particularities of each crisis. The duration and severity of the matched past crisis experiences suggest the road ahead will continue to be very rough. The specific matched crises of Indonesia, Malaysia, and Japan took 6, 7, and 10 years to disappear, respectively. This is suggestive that policy design should not only be case-specific, but should also be designed very proactively. Unless a shift in the policy structure is implemented in Europe, the dismal growth conditions in the current crisis countries are likely to continue for several years more.

Footnotes

1. In the remainder of the column, the euro crisis will refer mainly to the crisis of the periphery Eurozone countries, namely Greece, Ireland, Italy, Portugal, and Spain (GIIPS).

2. The terminology owes to Eichengreen (2008).

References

•CEPR Business Cycle Dating Committee (2014), “Eurozone mired in recession pause”, VoxEU.org, 17 June.

•Eichengreen, B (2008), “Sui generis EMU”, NBER Working Paper 13740.

•Frankel, J and G Saravelos (2012), “Can leading indicators assess country vulnerability? Evidence from the 2008–09 global financial crisis”, Journal of International Economics, 87: 216–231.

•Gupta, P, D Mishra, and R Sahay (2007), “Behavior of output during currency crises”, Journal of International Economics, 72: 428–450.

•Rose, A K and M M Spiegel (2010), “Cross-country causes and consequences of the 2008 crisis: International linkages and American exposure”, Pacific Economic Review, 15: 340–363.

•Rose, A K and M M Spiegel (2011), “Cross-country causes and consequences of the 2008 crisis: An update”, European Economic Review, 55: 309–324.

•Rose, A and M M Spiegel (2012) “Cross-country causes and consequences of the 2008 crisis: Early warning”, Japan and the World Economy, 24, 1–16.

•Sayek, S and F Taskin (2014), “Financial crises: lessons from history for today”, Economic Policy, forthcoming.

Leave a Reply