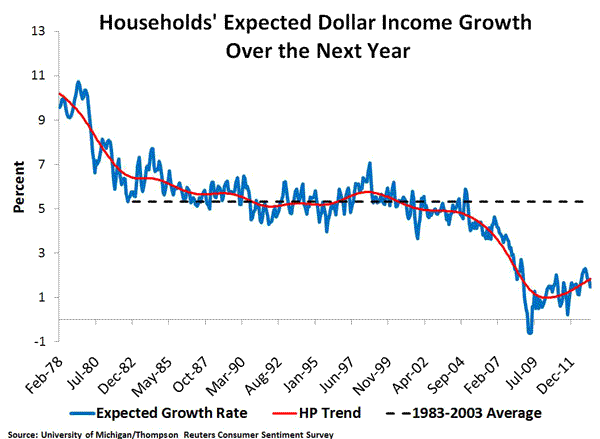

I recently lamented the Fed’s ongoing dereliction of duty as seen in the sustained declined of households’ expected nominal income growth:

In that post, I noted this observed decline was problematic for two reasons: (1) current nominal spending decisions are influenced by expected nominal income growth and (2) past nominal debt contracts were based on certain expectations of nominal income growth that did not happen. Here is what I specifically said on the latter point:

The figure also indicates that real debt burdens are higher than many households expected prior to the crisis. Look at the dashed line. It shows the average expected dollar income growth rate over the ‘Great Moderation’ period was 5.3%. Now imagine it is early-to-mid 2000s and you are taking out a 30-year mortgage and determining how much debt you handle. An important factor in this calculation is your expected income growth over the next 30 years. If you were average, then according to this data you would be forecasting about 5% growth rate. But that did not happened. Household dollar incomes declined and are expected to remain low. Nominal debt, however, has not adjusted as quickly leaving higher than expected real debt burdens for households.

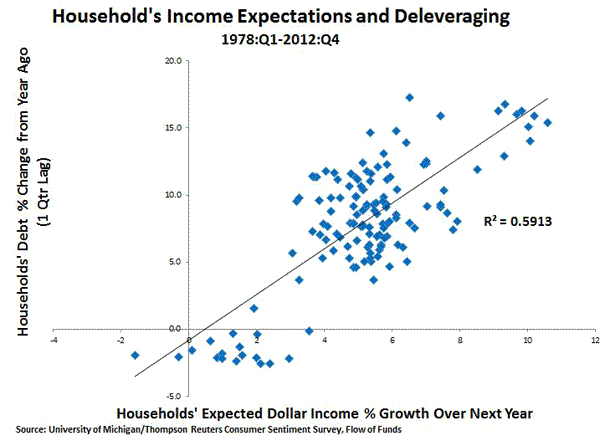

An important implication of this development is that households’ deleveraging over the past few years may not be so much about their weakened balance sheets as it is about the unexpected decline in their expected nominal income growth. Josh Hendrickson and I are working on a paper where we develop this point more fully and, among other things, report the figure below. It plots expected household nominal income growth against the percent change of nominal household debt:

This figure suggests that for households, expected dollar income growth matters a lot for deleveraging. It also implies “balance sheet recessions” are a byproduct of nominal income shortfalls. One policy implication, then, is that the Fed should have maintained aggregate nominal income growth at its expected path. It failed to do so in 2008 and has yet to fully make up for this shortfall.

I bring this up, because a new paper by Kevin D. Sheedy (hat tip Simon Wren-Lewis) shows that NGDP level targeting dominates inflation targeting for this very reason. It is much better at stabilizing the real debt burdens of households precisely because it is much better at stabilizing the growth path of nominal income. Here is his abstract:

Financial markets are incomplete, thus for many agents borrowing is possible only by accepting a financial contract that specifies a fixed repayment. However, the future income that will repay this debt is uncertain, so risk can be inefficiently distributed. This paper argues that a monetary policy of nominal GDP targeting can improve the functioning of incomplete financial markets when incomplete contracts are written in terms of money. By insulating agents’ nominal incomes from aggregate real shocks, this policy effectively completes the market by stabilizing the ratio of debt to income. The paper argues that the objective of nominal GDP should receive substantial weight even in an environment with other frictions that have been used to justify a policy of strict inflation targeting.

Fed officials should take note. So should ECB officials since this finding is particularly poignant for the Eurozone. It is time to fully embrace NGDP level targeting.

Leave a Reply