We know the Fed intends to taper off quantitative easing. We know the timing is dependent on progress in achieving a stronger and sustainable recovery in the labor market. Courtesy of San Francisco President John Williams, we have also know the time they expect to be confident of that recovery – this summer, which could be as early as the June FOMC meeting. Thus June is the earliest we could expect the Fed will begin scaling back the pace of asset purchases, with the expectation that quantitative easing will draw to a close by the end of this year.

June is earlier than I had anticipated. I had expected the Fed would want to be confident that the economy would not experience one of its Spring/Summer swoons. One would think fiscal tightening this year would magnify that concern. Via Bloomberg:

“We could very well in the summertime start seeing the effects of the fiscal tax increase and spending cut slow us down again,” said Joseph Gagnon, a senior fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics in Washington and a former Fed economist.

Moreover, given that inflation remains under the 2 percent target and it is likely that significant slack in the labor market will remain deep into 2014, there does not appear to be any need to rush into scaling back quantitative easing. Considering data lags, it would seem prudent for the Fed to wait until the fall or even winter before easing back on purchases.

To be sure, policymakers would probably argue that they could revert to a more aggressive pace of purchases should the data turn south. But even so, that is not likely the desired path. I don’t think they would want to increase the pace of purchases just two months after a decrease. I would expect they would want to be sure that they did not have to reverse course.

But that does not seem to be the case. Instead, it is evident that FOMC members anticipate ending asset purchases this year. This I find somewhat puzzling, as they seem to have reached a consensus that they need to be scaling back the asset purchase program on the basis of their own forecast, but that forecast itself anticipates that unemployment – what Vice Chair Janet Yellen described as the “the best single indicator of current labour market conditions”- will remains unacceptably high in the 6.8 to 7.3% range at the end of 2014. Indeed, arguably the Fed has fallen back into the trap of placing an implicit calendar date for the end of quantitative easing, rather than leaving the timing data dependent. It seems they want to end the program by the end of 2013, and are desperately hoping the data cooperates.

Assuming their intention is to end the program this year, to what extent will they color the data in such a way as to ensure it cooperates? For instance, it seems evident that the March employment report should call into question plans to slow the pace of quantitative this summer. Again, from Bloomberg:

“There’s a very strong message to the Fed here, which is that it’s too early to even think about exiting from easy policy,” said Ethan Harris, co-head of global economics research at Bank of America Corp. in New York. “This report suggests that they’re missing on both of their mandates: Inflation is too low and the labor market is too weak.”

This should be correct. The sub-100k nonfarm gain should raise red flags about the strength and sustainability of the labor market improvement. If the Fed holds true to the assertion that policy is data dependent, this should be correct as well:

“It helps that we’ve removed one source of uncertainty which is, how will the Fed react?” said Julia Coronado, chief economist for North America at BNP Paribas in New York. “Instead of asking how bad things need to get for the Fed to do more, it’s how good do they need to be before they stop helping.”

But at the same time, I am watching for signals that policymakers downplay this report or any other similarly weak reports. And lo and behold, today John Williams has an interview with the Wall Street Journal:

The economy could be on a strong enough footing by the second half of the year for the Federal Reserve to begin winding down its bond-buying programs, John Williams, president of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, said in an interview with The Wall Street Journal.

Mr. Williams said this has long been his view and a disappointing jobs report Friday wouldn’t alter his thinking too much. The Labor Department said Friday that employers added just 88,000 jobs in March, after expanding by more than 200,000 in three of the previous four months.

“We just have to get away from overreacting to one piece of data,” he said.

To be sure, the usual caveat is included:

Of course, his forecast is conditional on how the economy actually performs. “We just have to keep watching all of the economic indicators,” he said.

But how closely is the Fed watching the indicators? Or have they already effectively made a decision on the timing of QE’s demise? Be wary that the minutes will have a hawkish tone.

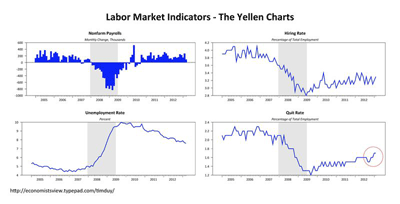

Of course, continue to watch for data that support the case for easing as early as June. With that in mind, February JOLTS report was released this morning. An update of the Yellen charts:

(click to enlarge)

Although the JOLTS data is of second-order importance, notice that the quits rate was revised up for January, a signal that existing employees are more confident of labor market prospects. Put it in the “stronger and sustainable” category.

Bottom Line: I had expected that the data flow would argue for the Fed to postpone tapering off QE purchases until late this year. The Fed seems to have a different view, thinking that the data flow argues for ending QE by the end of this year. My expectation is that the Fed is being overly optimistic and will find that summer is too early to being tapering off QE. That seems to be the message from the bond market as well; yields aren’t exactly soaring. But the ease by which SF Fed President John Williams is willing to dismiss the most recent jobs report suggests data may be less important than we have been led to believe.

Leave a Reply