Chief Justice John Marshall, in 1819, once described policymakers’ great influence, remarking, “The power to tax involves the power to destroy.” With rising fiscal deficits and a desperate need to raise revenue, many nations have come up with various tax solutions to raise billions of dollars.

One hotly contested idea in the U.S. and Europe lately, and once advocated by John Maynard Keynes during the Great Depression, is a financial transactions tax imposing a cost on buys and sells of stocks or bonds.

The latest proposal in the U.S. was introduced by Congressman Keith Ellison. His bill would add a tax of 0.5 percent onto the sale of stocks, 0.1 percent on bonds and 0.005 percent on derivatives or other investments. To put this in a buyer’s frame of mind, when an investor purchased $10,000 in stock shares, the financial transactions tax would tack on an additional $50.

Last year Congressman Peter DeFazio proposed a similar act, suggesting a tax imposition of 0.03 percent on financial transactions. The new tax was touted in its ability to raise $350 billion in new revenue over the next nine years, without acknowledgement of the drawbacks it might place on the economic system.

Proponents say a transaction tax would discourage short-term trading, with little effect on long-term investors. Keynes once argued that it would improve market quality by curtailing short-term speculation, according to Daniel Weaver, a professor of finance at Rutgers Business School.

Opposition to a financial transaction tax says the extra cost would undermine liquidity, adversely affect market quality and distort the value of a security. Whereas incentives act as a dose of Lipitor to today’s weak monetary system, unnecessary taxes add cholesterol, delaying a smooth economic recovery, or worse, causing the economic equivalent of a heart attack. In some cases, the Robin Hood deed of “stealing from the rich to help the poor” backfires and ends up negatively affecting all investors.

In his paper analyzing tax law reforms that affect the financial industry, Tulane Law Review Professor Richard T. Page comments on four proposals in the works throughout Europe and the U.S., evaluating them under the guidelines of what makes a “good tax.”

Page writes good taxes should be effective in raising revenues and addressing the U.S. budgetary imbalance. They should reduce undesirable behavior, similar to sin taxes on cigarettes. They should be fair, and finally, they should minimize reductions in desirable behavior. This means a tax should not discourage a desired behavior “to the point that the activity does not take place” because individuals change their behavior or the cost of compliance is expensive or time-consuming.

Page concludes that under these standards, “taxing financial transactions would just be foolish revenge, generating regrettable outcomes.”

In a paper titled, “Security Transaction Taxes and Market Quality,” Anna Pomeranets of the Bank of Canada and Daniel Weaver of Rutgers analyzed the historical precedence of financial transaction taxes by reviewing the results of 11 research papers that looked at the relationship between a security transaction tax and market quality in terms of volatility or volume.

Pomeranets and Weaver reviewed market quality to answer the following questions: Is a Robin Hood tax effective at reducing volatility and speculative trading? Does it affect volume across equity markets? How are stock prices affected?

Across 28 various security transaction tax (STT) changes in 11 countries, they saw no significant relationship between the tax and volatility. In other words, short-term speculation was not diminished. The team also found “an increase in the STT is accompanied by an increase in spreads” and that “volume moves in the opposite direction of the tax change.” They also found that there was a direct relationship between the tax and price impact.

Pomeranets and Weaver conclude, “Taken together, our results suggest that the imposition of an STT will harm market quality.”

Eastern European Fund Portfolio Manager Tim Steinle has been following the correlation between Hungary’s banking system and its financial transaction taxes enacted in 2010. Intended to be a temporary measure for two years to help the country repair its finances, one of the levies included a 0.5 percent tax on banks’ assets.

By March 2011, OTP bank, Hungary’s largest lender, reported that it had a fourth-quarter profit decline of 15 percent. Trouble for the bank continued in the first quarter, with its net profit falling 12 percent year-over-year due to the impact of a special banking tax. Excluding the tax, the profit of OTP would have risen by 4 percent.

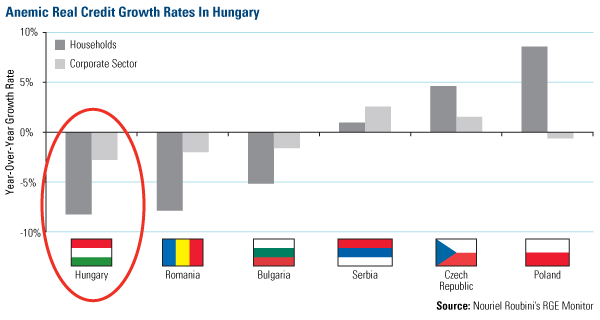

It wasn’t only one Hungarian bank that was negatively impacted. Bank credit growth rates across Hungary also plummeted due to the hefty bank levies imposed. In an earlier Investor Alert, we highlighted the chart below in May 2011, which shows a year-over-year credit growth rates across Eastern Europe in May 2011. Hungary’s household and corporate sector credit growth rates were anemic compared to other Eastern European countries.

Could a transaction tax have a similar unintended consequence for American banks? While the jury is still out on that answer, Hungary’s example is a reminder to policymakers to comprehensively consider the rewards of collecting a Robin Hood tax along with the risks.

Also read The Right Formula for Markets where I contrast the financial industry’s regulations to the racing industry, which has fine-tuned rules to respect the risks and rewards of the sport.

Leave a Reply