Global equity markets surged this today on the back of supportive comments from ECB President Mario Draghi. Borrowing from FT Alphaville, who borrowed from Bloomberg:

Draghi Says the Euro Is Irreversible

Draghi says ECB will do whatever needed to preserve the euro – Draghi Says ECB Ready to Do ‘Whatever It Takes’ to Preserve Euro

*DRAGHI: YIELDS DISRUPTING POLICY TRANSMISSION ARE IN ECB REMIT

*DRAGHI SAYS ECB WILL DO WHATEVER NEEDED TO PRESERVE THE EURO

*DRAGHI SAYS `BELIEVE ME, IT WILL BE ENOUGH’

*DRAGHI SAYS THE ECB IS READY TO DO WHATEVER IT TAKES FOR EURO

*DRAGHI SAYS THE EURO IS IRREVERSIBLE

*DRAGHI SAYS DON’T UNDERESTIMATE POLITICAL CAPITAL IN THE EU…

*DRAGHI SAYS FIREWALLS `READY TO WORK MUCH BETTER THAN IN P…

Draghi Says Euro-Area Much Stronger Than People Acknowledge

*DRAGHI SAYS LAST SUMMIT WAS `REAL SUCCESS’

It looks like Draghi finally found that panic button. This is crucial, as the ECB is the only institution that can bring sufficient firepower to the table in a timely fashion. His specific reference to the disruption in policy transmission appears to be a clear signal that the ECB will resume purchases of periphery debt, presumably that of Spain and possibly Italy. The ECB will – rightly, in my opinion – justify the purchases as easing financial conditions not monetizing deficit spending.

So far, so good. But there is enough in these statements to leave me very unsettled. First, the claim that the Euro is “irreversible” should send a shiver down everyone’s backs. Sounds just a little too much like “the crisis is contained to subprime” and “Spain will not need a bailout.” Second, the bluster that “believe me, it will be enough” is suspect. The ECB always thinks they have done enough, but so far this has not been the case. Moreover, he is setting some pretty high expectations, and had better be prepared to meet them with something more than half-hearted bond purchases.

Also, note that despite Draghi’s bluster, the rally in Spanish debt send yields just barely below the 7% mark. A step in the right direction, but also a signal that investors still worry that Spain will need a bailout despite additional ECB action.

More distressing to me was Draghi’s clearly defiant tone, reminiscent of comments earlier this week from German Finance Minister Wolfgang Schäuble. The message is that Europe has done all the right things, it is financial market participants that are doing the wrong things. What we have here is a failure to communicate. European leaders believe they have made remarkable progress in the context of the political realities they face, and want credit for that expended “political capital.” Financial markets are saying the the progress politicians see as “remarkable” barely moves the needle compared to what is necessary to resolve the crisis.

The classic breakup line is “it’s not you, it’s me.” It is a classic line because everyone knows it’s a lie. I suppose at least Draghi is living up to the lie, essentially saying that “it’s not me, it’s you.” European policy makers simply will not accept what financial markets are telling them. As a consequence, Draghi doesn’t act until his back is against the wall, they engage in some half-hearted program, conditions ease temporarily, and then the ECB drifts back into the woodwork, claiming they have done all they can do. Lather, rinse, repeat. Why should we believe this time is any different?

As to the claims of Euro-area strength, Isabella Kaminska has this to say:

The second thing we think is interesting is Draghi’s point that the euro area is much stronger than people realise. This *we think* is very encouraging indeed. And whilst many might disagree, we actually don’t think it’s a bluff at all. Not only does it tie very much with Draghi’s previous comments about how well Ireland is doing, it suggests Draghi feels the market may be over focusing on the wrong metrics. Or, in other words, that there may be other economic gauges that are much more reflective of what’s really going on.

I don’t usually disagree with the FT Alphaville staff, but I disagree on this point. I don’t find it encouraging at all. I think it is exactly the kind of delusion that leads to spectacular policy failure. I can’t wait for the ECB to pull out the statistics that explain exactly how we don’t get it. I want to see the explanation of how this reflects the strength of the European economy:

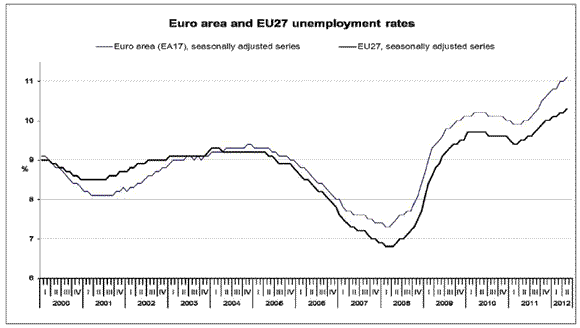

Call me crazy, but I get a little disconcerted when unemployment rates exceed 11%. And, is it just me, or isn’t the gap between the Eurozone and EU27 rates increasing, suggesting that being a member of the Eurozone is on net a negative?

And what about the lasting impact of this crisis? I get unnerved by the structural damage due to Washington’s acceptance of 8+% unemployment rates in the US. That is absolutely trivial compared to Europe. Spain is at 24.6%, with a a youth unemployment rate of 52.1%. We called this a Great Depression in the 1930’s, not a sign of strength. Greece was at 21.9% in March. France and Italy are in the double digit range. And the “remarkable” Ireland has an unemployment rate at 14.6%. Simply put, the mindless pursuit of fiscal consolidation is scarring a generation of workers, perhaps irrevocably. There will be a cost that offsets the benefits of the structural change European leaders seem intent on pursuing in the absence of fiscal stimulus.

Also, how much damage is being done to the European financial system? Gillian Tett reports on the fracturing of banking along national boundaries:

The bankers, however, were alarmingly precise: amid all the speculation about Grexit, they told me, banks are increasingly reordering their European exposure along national lines, in terms of asset-liability matching (ALM), just in case the region splits apart. Thus, if a bank has loans to Spanish borrowers, say, it is trying to cover these with funding from Spain, rather than from Germany. Similarly, when it comes to hedging derivatives and foreign exchange deals, or measuring their risk, Italian counterparties are treated differently from Finnish counterparties, say.

The halcyon days of banks looking on the eurozone as a single currency bloc are over; cross-border risk matters. To put it another way, while pundits engage in an abstract debate about a possible break-up, fracture has already arrived for many banks’ risk management departments, at least when it comes to ALM in their eurozone books.

The way this is heading is toward a continent with limited cross-border capital flows with a fiscal policy regime that limits members ability to use fiscal policy, all under a single monetary policy. This is a recipe for long-term recession, not economic strength. And it is also a system that will become increasingly susceptible to asymmetric shocks.

Finally, note that we are well past the point where just bringing down interest rates in peripheral economies is enough to turn the ship around. The 10-year UK bond yield stands at 1.48% today. And despite low rates, the UK economy continues to struggle:

The UK’s double-dip recession has deepened sharply and unexpectedly, leaving the economy smaller than it was when the coalition government took office two years ago….

…critics of Mr Osborne’s austerity programme, which aims to eliminate the structural current deficit in five years, said the data showed his efforts were self-defeating.

“As we warned two years ago, David Cameron and George Osborne’s ill-judged plan has turned Britain’s recovery into a flatlining economy and now a deep and deepening recession,” said Ed Balls, shadow chancellor for the Labour party.

In short, it’s not just about interest rates.

Bottom Line: Draghi has his back up against the wall, and is now forced to step back into the crisis. A near-term positive, to be sure. It might be a longer-term positive if the ECB would commit to an open-ended purchase program based on macroeconomic objectives (sound familar?). But that is likely too much to ask, as he has yet to admit that the entire policy approach is failing the Eurozone, not just in the short-run, but in the long-run as well. Until policymakers fundamentally rethink their approach to the crisis, expect the optimisim-pessimism cycle to continue. Right now, the best case scenario I see is that the ECB will act to hold the Eurozone largely together, but at the cost of protracted recession.

Leave a Reply