Another day and the markets remain fixated on whether Greece comes to a “voluntary” arrangement with its creditors. The key word is “voluntary” because the myth of “voluntary compliance has to be sustained so that those deadly credit default swaps avoid being triggered.

But let’s face it: Greece is a pimple. If the rest of the euro zone could cut it lose with a minimum of systemic risk, Athens would have long gone the way of Troy. The real issue is whether the credit default swaps trigger such a huge mess with the counterparties that it creates renewed systemic stress which more than offsets the benefits to the holders of the CDSs.

The more interesting question is: suppose Greece finally does get a deal? I realize everybody says it is a “one-off”, but do you really think the Irish, Portuguese, or even the Spanish and Italians will go along with that, particularly if (as is likely) they continue to experience double digit unemployment and minimal growth?

Now you could argue that Portugal and Ireland, like Greece, are but small components of the European Union and could well be covered in one form or another via the existing backstops established over the last several months, notably the European Financial Stability Fund (EFSF) and the European Stability Mechanism (ESM).

But you can’t say this about Spain, which remains the real elephant in the room – not Italy – even though Spain’s borrowing costs remain lower than Italy’s. This is perverse.

Though Italy has a high sovereign debt, it has a low private debt (the product of years of high budget deficits, but that’s the story for another blog). Italy has a fiscal deficit that is low relative to most economies today. It already has a primary surplus. The greater than expected past expansion of the ESCB and the current ongoing LTROs are likely to absorb panic and forced selling of Italian debt. The Italian 10-year yield could fall back below 5% (having already fallen from the 7% plus levels, pertaining a mere 6 weeks ago).

In theory, this rally in bond yields should lead to a reassessment of the gravity of the Italian problem and therefore the European sovereign debt and banking problem. That could be positive for equity markets and, indeed, has been so since the start of the year.

But does Spain truly deserve the borrowing advantage it now has in relation to Italy? Its 10-year bonds are yielding some 60 basis points lower. True, its sovereign debt to GDP ratio is low at about 75%, but part of its enormous private debt will almost certainly have to be “socialized.” Moreover, Spain has virtually the highest non-financial private debt-to-GDP ratio of all the major economies. Its ratio is almost twice that of Italy’s. Its fiscal deficit last year was probably higher than the official estimates, close to 9% of GDP (the previous Socialist government routinely lied about its figures – in fact, no country, not even the US, has lied more extensively about the condition of its banks. Spain, relative to GDP, has the largest shadow real estate inventory in the world, with the possible exception of China, which probably doesn’t even have a reliable second or third set of books).

Let’s be clear about one thing: this is not a tale of Mediterranean “profligacy”, as least as far as public spending was concerned. Anybody looking at Spain through a sensible financial balances framework in the mid-2000s would have observed that the private sector was being squeezed badly by the fiscal drag. The external position was in deficit (current account) which means the public and external balances were draining growth from the economy. Yet it still boomed up into the onset of the crisis. How did that happen?

The profligates were all in the private sector, although you could readily argue that the government’s “responsible” fiscal policy created the conditions for a private sector debt binge. Prior to 2008, the Spanish economy was held out as the darling of Europe however the reality was quite different. The country was running budget surpluses by 2005 and foreign investment was booming. Most of this investment went into construction which was stimulated by a massive real estate boom.

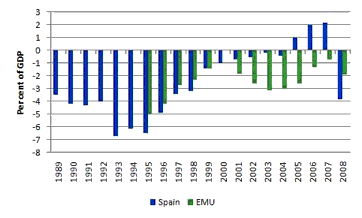

A few years ago, using data from Data from the Banco de España (central bank) Bill Mitchell graphed the national budget deficit as a percentage of GDP for Spain and the EMU overall from 1989 to 2008 (data for the EMU clearly didn’t start until 1995). As Mitchell notes, one can observe the tightening of fiscal positions as the Growth and Stability Pact provisions were forced on the EMU nations:

EMU and Spain: Budget deficit % of GDP, 1989 to 2008

Consistent with a tightening fiscal position leading to surpluses in 2005, the only way that this boom could continue was for the private sector to go increasingly into debt. That is exactly what happened and because the property boom was so large the debt levels were also very high – average household debt tripled. And that, in contrast to Italy, is the core problem with which Spain is dealing today to a substantially greater degree than Italy. So it’s wrong to lump the two together interchangeably as the markets have been doing. Paella and pasta don’t mix well together.

Okay, but that was the previous Zapatero Administration. Now we supposedly have a new “responsible” conservative government that promises to carry out the same policies even more resolutely. And look how successful they’ve been: Spain’s jobless claims shot up a further 4% in January from December to 4.59 million, a sign that the euro zone’s fourth-largest economy is still shedding jobs at a record rate. All sectors posted more claims but the rise was sharpest for services at 5.1%. In construction, weighed down by a four-year property slump, the number of residents registered as job seekers rose 2.1%. Compared with the same period a year ago, overall claims rose 8%. GDP contracted 0.3%.

Okay, “give them time”, argue the defenders of the new government. And, if the Rajoy Administration was truly embarking on a new policy course, that would be a fair comment. Unfortunately, this government has signed on to even tighter fiscal policy rules. Somehow they are expected to suck demand out of their economies through tax increases and spending cuts, but when the slower growth that results in means the target for deficit reduction is not met, the Spanish, like their Greek, Irish, Portuguese and Italian counterparts, will be punished for it.

Even the Rajoy Administration implicitly appears to recognize this danger, as it is already moving the goalposts in regard to its spending cuts targets as a percentage of GDP. Unfortunately, they blame this on external circumstances beyond their control. To the extent that they agree to submit themselves to rules which were routinely disobeyed by the Germans and French during the EMU’s inception, that is true, although the Spanish government refuses to acknowledge that their resolute tightening fiscal policy ex ante might well have something to do with the fact that Spain’s economy continues to deflate into the ground ex post. Remember, the history of the Stability and Growth Pact has long demonstrated that these nonsensical rules are already impossible to keep within during a significant downturn. And now the new Spanish government wants to tighten them even further and invoke pro-cyclical fiscal reactions earlier.

This, at a time when the national unemployment rate is approaching 23%, and the youth unemployment rate (25 years or younger) is at 49%, according to the latest Eurostat data.

So nearly 50 per cent of willing workers under the age of 25 in Spain are without work and will remain like that for years to come. That will damage productivity growth for the next decade or more. It is an indication that the monetary system has failed and attempting to reinforce those failures with more austerity will only make matters worse. The new government’s proposed fiscal policy “reforms” are particularly toxic policy mixture for Spain.

Of course, the ongoing threat of a disorderly default in Greece also remains a potentially dangerous area if it is not contained by the ECB’s actions. But it’s more interesting to see what happens as the magnitude of Spain’s problems become more apparent. Will the troika tell Spain that a Greek style 70% haircut is not in the cards? Will they try to suggest that the government is rife with corruption, that the country is chock-a-block full of scoff-laws and tax evaders, and that the efficient Germans would do a much better job of collecting taxes?

Spain is still a relatively young democracy. The transition began a mere 37 years ago when Francisco Franco died in 1975, but there was an attempted coup by Antonio Tejero as recently as 1981. This is worth pondering whilst observing the implosion of Spain’s economy. The decision for Europe’s bosses is this: they must ultimately confront the consequences of their policy choices. They can destroy the eurozone by continuing with the same failed mix of policies or by salvaging it by adding what has been missing from the outset: a mechanism for shifting surpluses to the deficit regions in the form of productive investments(as opposed to handouts or loans). Turning states like Spain into sundrenched economic wastelands within the eurozone, and forcing the rest of the currency area into a debt-deflationary spiral, is a most efficient way of blowing up the whole system and possibly threatening the very existence of Spanish liberal democracy itself.

Disclaimer: This page contains affiliate links. If you choose to make a purchase after clicking a link, we may receive a commission at no additional cost to you. Thank you for your support!

“Turning states like Spain into sundrenched economic wastelands within the eurozone, and forcing the rest of the currency area into a debt-deflationary spiral, is a most efficient way of blowing up the whole system and possibly threatening the very existence of Spanish liberal democracy itself.”

Hilarious. It is no doubt the Eurozone has to face many challenges in the following years; but this conclusion outstands reality. As far as I’m concerned, the author has no idea at all of how the majority of the Spanish society backs and supports liberal democracy. It is true there is a lot of ressentment towards politicians due to the situation Spain has been brought to; but the very existance of democracy is not questioned at all. Reforms to Spanish instituons round many Spaniards thoughts as a way to push a greater control of politicians, but democracy is here to stay.

“Spain is still a relatively young democracy.” This is a statement that has to be rebated with history. Spain has been fighting for democracy for 200 years: I shall remind the author the very first Spanish constitution is from 1812; a very liberal constitution by the way. It is also true it only had effect for three years (1821-1823), but it started a long journey towards democracy in Spain; an ardous journey that has given Spain a rich history of Constitutional texts: 1833, 1868, 1876, 1931, 1978 (& unratified projects in 1856, 1873), texts that rflect the fight between monarchy tradition and progress towards democracy. So, as things have evolved, democracy in Spain is to stay.

“Spain has virtually the highest non-financial private debt-to-GDP ratio of all the major economies.” I also want to remind the author the UK is the most indebted country by far, not Spain; and so it says the BBC:

http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/business-15748696

The difference is UK still has control of its monetary policy and Spain doesn’t. The question is ‘How long will the markets trust the UK?’ It’s public and private debt are larger than that of Spain and so is its deficit. A point this article’s british author may have forgotten…