Recent data show that the current-account deficits of Greece, Italy, Spain, and Portugal have improved at a rapid pace and are actually close to being balanced. This column reviews recent research that shows this adjustment has been remarkably fast. Compared to mid-2008, these four nations have switched expenditures at a rate that is much higher than the typical rate observed during large rebalancing episodes. A key requirement for a return to a post-crisis Eurozone is thus on its way to being met.

The large current-account imbalances that had emerged within the Eurozone in the years leading up to 2008 reflected heterogeneous developments in unit labour costs and spending patterns across the currency union.

The heterogeneity of the single economies has made the area as a whole vulnerable to external shocks such as the 2007-2009 financial crisis. The ensuing European debt crisis has also been worsened by the large scale of current-account imbalances, which have “contributed to the severity of the economic contraction and damaged banking systems and sovereign creditworthiness” (see Lane and Pels 2012: p.2).

Because current-account imbalances are indicative of underlying differences in macroeconomic fundamentals across the currency union,1 restoring uniform competiveness across the Eurozone has become a policy objective for many European policymakers. For example, Draghi (2012) states that “Europe’s future prosperity requires member countries to be competitive individually in order to be competitive jointly and thrive in an open, global economy”. However, the heterogeneous developments in wage setting and public and private spending patterns that caused the current-account imbalances had taken a decade to develop, thus giving rise to concerns that closing current-account imbalances also might take a prolonged period. Indeed, given the lack of the possibility of exchange-rate depreciation, external adjustment within currency unions is generally thought to be a slow and costly process.2

Current-account balances in the southern Eurozone are rapidly improving

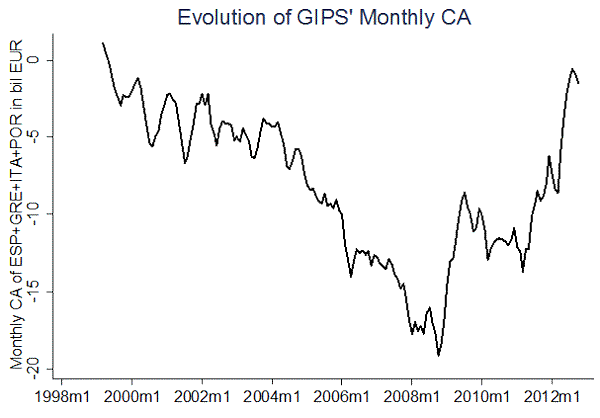

Against the backdrop of these considerations, it is worthwhile to point out that rapid current-account rebalancing is actually well underway at the current juncture. Figure 1 from my paper (Auer 2013) documents the joint monthly current-account balance of Greece, Italy, Portugal, and Spain (GIPS).3 Figure 1 documents that in the last years, these four nations have nearly rebalanced their joint current account. The monthly current-account deficit had increased steadily from 1998 to late 2008, peaking at a monthly rate of well over EUR 17 billion per month (i.e. at an annualised rate of EUR 204 billion). Since then, it has sharply reversed. In the third quarter of 2012, the average seasonally adjusted monthly current-account deficit of these four nations together stood at less than EUR 2 billion (EUR 24 billion at an annualised rate).

These developments suggest that the GIPS nations have undergone an expenditure switching in excess of EUR 180 billion per year, which constitutes a sizeable fraction of their overall consumption.

Figure 1. Evidence of GIPS’ monthly CA

The current-account rebalancing took place at a rapid pace and the speed of adjustment has even increased substantially over the course of the last six months (see Figure 1).

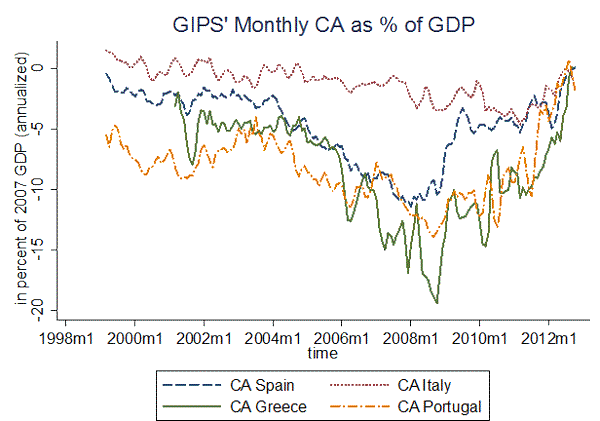

Figure 2 (from Auer 2013) documents that all four countries have achieved substantial external adjustment. It plots the evolution of the current-account balances of Greece, Italy, Portugal, and Spain as a percentage of GDP.4

Current-account deficits have been the smallest in Italy (red dotted line), where the deficit was in the range of -2 to -4% of current GDP during 2008 to 2011. Reflecting the low need for adjustment, the country’s CA deficit has only improved somewhat during the second half of 2012, nearly reaching 0 during July 2012.

The monthly current-account deficit of Spain (blue dashed line) peaked at over -10% of GDP in 2008 and substantially improved to -5% in the course of 2009. During the third quarter of 2012, the magnitude of the deficit has been lower than a per cent of GDP, on a seasonally adjusted basis even reaching positive territory in October.

The monthly current-account deficit of Portugal (orange dash-dotted line) had exceeded -10% of GDP for large parts of 2008 and 2009. It has substantially improved thereafter and, during the third quarter of 2012, it was less than -2% of GDP on a seasonally adjusted basis.

In 2007 and 2008, the monthly current-account deficit of Greece (green solid line) had at times exceeded -15% of GDP. The country’s current account improved to the -10% region during 2010 and then rapidly improved to a deficit of around a per cent of GDP during the third quarter of 2012 (when adjusted seasonally).

The size, the speed, and the uniformity of the current-account improvement in these four nations could indicate an improvement of macroeconomic fundamentals or of the deep recession in these nations. If the recent speed of adjustment prevails, it is not impossible that the near future holds substantial current-account surpluses for these nations.

Figure 2. GIPS’ monthly CA as % of GDP

In fact, the speed of current-account rebalancing in the southern Eurozone is actually much faster than the typical rate of current-account rebalancing following large imbalances. Chinn and Wei (2008) construct a sample of over one hundred rebalancing episodes from 1970 onwards and estimate the rate of current-account persistence.

Repeating Chinn and Wei’s exercise for the monthly sample in the post crisis-period in Greece, Italy, Spain, and Portugal, the coefficient on the one-year lagged monthly current account is equal to 0.576. This rate of current-account persistence in the southern Eurozone is below any of the average rates estimated by Chinn and Shang-Jin Wei (2008), be that for the average persistence rate for fixed-exchange-rate regimes (0.63, see their Table 1A), for flexible-exchange-rate regimes (0.73, see their Table 1A), or for the average rate of current-account adjustment in industrialised countries (0.867, see their Table 2). 0.576 is also below the rates of current-account persistence found in Atish et al. (2010).5

Of course, these recent developments also have to be interpreted with care as it is not yet clear whether the reduction of current-account deficits reflects only temporary cuts in private and public spending or a permanent improvement in the competiveness of these countries.

Conclusion

A key requirement for the Eurozone to achieve long-term success is that corrective forces are at work which limit external imbalances.6 This column documents that Greece, Italy, Portugal, and Spain are close to achieving a balanced current account.

These patterns indicate that one of the key requirement for the end of the European debt crisis is on its way. In as such, there is no evidence that the institutional setup of the European Monetary Union will lead to ever-increasing imbalances akin to the ones in the Bretton-Woods system. In fact, the speed of current-account rebalancing in these four nations is actually faster than the typical rate of adjustment found after other episodes of large current-account imbalances.

This rebalancing also has to be seen in the light of the current discussion on the origins and implications of the large Target2 imbalances within the Eurozone. In a panel analysis, I analyse the role that the provision of central-bank liquidity (visible in Target2 balances) played in smoothing the ‘sudden stop’ and the partial reversion of private capital flows that had financed current-account imbalances before the onset of the financial crisis in 2007.

Given that current-account imbalances are rapidly diminishing, Target2 balances will be reduced once private capital flows return to the southern Eurozone. Given the current signs that private investors are rediscovering these troubled financial markets (see Atkins and Watkins 2013), this may happen in the not-too-distant future.

Disclaimer: The views expressed here are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the institutions with which they are affiliated.

References

•Ralph Atkins and Mary Watkins (2013), “Back in the zone”, Financial Times, 29 January.

•Raphael A Auer (2013), “What drives Target2 Balances? Evidence from a Panel Regression?”, Paper prepared for the 57th Panel Meeting of Economic Policy, April.

•Martin Berka, Michael B Devereux, and Charles Engel (2012), “Real Exchange Rate Adjustment in and out of the Eurozone”, The American Economic Review: Papers & Proceedings 102(3), 179–185, May.

•Mario Draghi (2012), “Competitiveness – the key to balanced growth in monetary union” remarks at Treasury Talks, “A European strategy for growth and integration with solidarity”, Directorate General of the Treasury, Ministry of Economy and Finance – Ministry for Foreign Trade, Paris, 30 November.

•European Commission (2011), “Scoreboard for the surveillance of macroeconomic imbalances: envisaged initial design”, SEC (2011) 1361, November.

•Philip R Lane (2010), “External Imbalances and Fiscal Policy”, Trinity College IIIS Discussion Paper No. 314, January.

•Philip R Lane and Gian Maria Milesi-Ferretti (2012), “External Adjustment and the Global Crisis”, Journal of International Economics, 88(2), 252-265, November.

Philip R Lane and Barbara Pels (2012), ”Current Account Imbalances in Europe”, IIIS Discussion Paper No.397, April.

•Richard Portes (2009), “Global imbalances”, in M Dewatripont, X Freixas, and R Portes (eds.) Macroeconomic stability and financial regulation: Key issues for the G20, Centre for Economic Policy Research.

______

1 CA balances are not the only determinant of differences in competiveness. The European Commission’s “Macroeconomic Imbalance Procedure” also takes into account the net international asset position, the real effective exchange rate, export market shares, unit labor costs, housing prices, private sector credit flows, general government debt, and unemployment when determining whether countries are out of balance (see European Commission 2011).

2 Whether external adjustment in currency unions is inefficient is a contentious issue (see Berka et al. (2012) for an analysis of this issue in the EA during the pre-crisis period). Lane and Milesi-Ferretti (2012) document the external adjustment following the financial crisis. Among others, they also examine whether adjustment differs between countries with fixed and with flexible exchange rates, finding that the adjustment in deficit countries “took place primarily through a compression of output and demand.” (see p. 253). Lane (2010) examines how government spending patterns affect external balances.

3 The displayed time series is constructed by summing over the monthly CA balance of these four nations, seasonally adjusting, and constructing a 3-months moving average (to reduce variability). Sources: ECB’s Statistical Data Warehouse and websites of the national central banks of Greece, Italy, Portugal, and Spain. Data for Ireland is not available on a monthly basis.

4 All four series are seasonally adjusted and the lines present 3-months moving averages. The series are normalised by pre-crisis GDP so that changes are driven by changing CA balances rather than contracting GDP (without this normalisation the recent improvement of the CA balances would even be more pronounced). For correct interpretability, the monthly CA balance is divided by the monthly GDP (both seasonally adjusted).

5 It is difficult to compare the speed of CA rebalancing in the EA to other episodes of CA reversals during crises, as the latter took place mostly in emerging markets. However, it is noteworthy that also in emerging markets, CA imbalances are not always sharply reduced after a currency crisis (see Milesi-Ferreti and Razin 1998 and 2000).

6 CA imbalances might even have contributed to the emergence of the tensions on financial markets that have led to the sudden stop of within-EA capital flows. For example, Portes (2009) argues that large CA imbalances combined with sudden stops put the financial intermediation process under stress and hence generate the conditions that lead to financial crisis.

Leave a Reply