Inflation in China is, if not quite galloping, at least trotting along at a decent clip:

Inflation quickens in China, India; Beijing raises reserve ratios

BEIJING/MUMBAI, June 14 (Reuters) – Inflation in China and India accelerated in May, prompting Beijing to lift bank reserve requirements on Tuesday and keeping pressure on India to raise interest rates later this week even as Asia’s two big growth engines show signs of slowing and recovery stalls elsewhere.

China’s consumer price inflation hit a 34-month high of 5.5 percent, keeping inflation-fighting at the top of the agenda for Beijing, which sees little chance of the current slowdown from last year’s 10 percent-plus growth turning into a hard landing.

Inflation in China has been an important contributor to the subtle but very significant change in the pattern of trade that we’ve seen between the US and China. For nearly 20 years, the story of the US’s trade with China was a simple and predictable one: month after month, year after year, the US imported more from China. US exports to China also grew, but at a slower rate, and so the US’s trade deficit with China grew steadily. That story had grown so monotonous that by the mid-2000s many people had stopped paying attention to it.

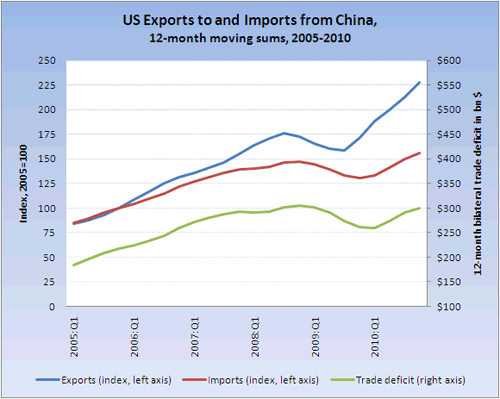

But over the past couple of years that pattern has been broken. The big difference is that now, US exports to China are starting to grow rapidly, while US imports from China are growing slowly at best. Since the start of 2008, US exports to China have risen by about 40%, while US imports have risen by only about 10%. Granted, US exports are rising from a much lower base than imports, so it will be a while before we see that change actually start to reduce the US’s overall trade balance with China… but even so, the bilateral trade deficit (goods + services) has been roughly constant for almost four years now, as shown in the chart below.

This striking change is the result of two related forces: the strong growth of the Chinese economy (particularly relative to the anemic US economy), and the rise in Chinese prices. Higher inflation in China means that Chinese-made products are now less competitive than they were a few years ago, inhibiting US imports. And at the same time, Chinese inflation makes US-made goods and services look somewhat cheaper to Chinese consumers than they used to.

Since there’s probably no reason to expect either the growth differential or the inflation differential between the US and China to reverse course any time soon, it’s reasonable to expect these recent trends in US-China trade to continue. And if so, then I wouldn’t be surprised if we may be near the all-time peak of the US-China trade deficit. Within a year or two the US-China trade balance could actually begin to show sustained (and not recession-driven) improvement. And wouldn’t that be a striking change from what we’re used to? We could be near the end of an era…

- Bulenox: Get 45% to 91% OFF ... Use Discount Code: UNO

- Risk Our Money Not Yours | Get 50% to 90% OFF ... Use Discount Code: MMBVBKSM

Disclaimer: This page contains affiliate links. If you choose to make a purchase after clicking a link, we may receive a commission at no additional cost to you. Thank you for your support!

Leave a Reply