Lots of action in oil prices today, as the unrest has spread from Tunisia and Egypt– which produce relatively modest amounts of crude oil– to Libya, the country sandwiched between them, and producer of over 2% of the world’s crude oil supply. Rather than try to guess where those developments are going to lead, I wanted today to try to make sense of another equally striking development in oil markets over the last 6 weeks– the disparity between the price of oil in the Midwest United States and that elsewhere in the world.

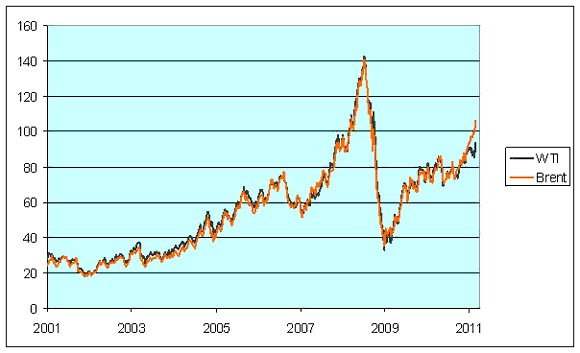

The graph below compares the price of West Texas Intermediate for delivery in Cushing, Oklahoma with that for North Sea Brent in Europe. Usually you can hardly tell the two apart on a long-term graph like this.

Weekly price of WTI and Brent in dollars per barrel, Jan 5, 2001 to Feb 22, 2011. Historical data from EIA; Feb 22 values from Oil-Price.net.

But in the last few weeks, the discrepancy has at times exceeded $15 a barrel.

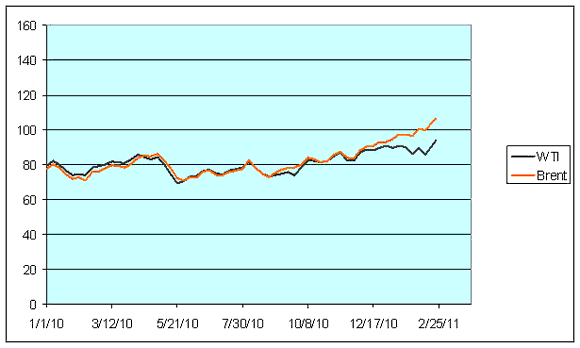

Weekly price of WTI and Brent in dollars per barrel, Jan 1, 2010 to Feb 22, 2011. Historical data from EIA; Feb 22 values from Oil-Price.net.

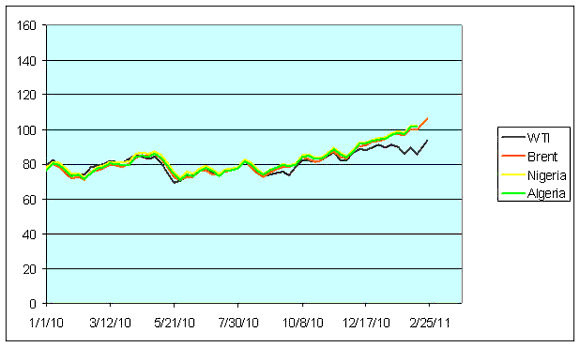

The prices of other high-quality international crudes, like Nigerian Bonny Light and Algerian Sahara Blend, have hugged close to Brent as they also pulled away from the WTI.

Weekly price of assorted grades in dollars per barrel, Jan 1, 2010 to Feb 22, 2011. Data source for Nigerian and Algerian crudes: EIA.

Stuart Staniford and Donald Marron have discussions of this, with the Oil Drum having the most thorough treatment. An influx of Canadian crude through pipelines delivering to the Midwest, along with impressive production gains from North Dakota, are bringing a lot of new oil to Cushing, depressing the price there relative to other locations.

But the fact that more oil is being produced and delivered locally is not an adequate explanation for the price discrepancy. There is a very fundamental economic principle that goods that are close substitutes and easily transported should sell for a similar price even if the fundamentals of local supply and demand differ across regions. The economic force that ensures this is arbitrage. Whenever price differentials emerge, there are very powerful monetary incentives for anyone to buy in the market where the price is low in order to sell in the market where price is high. The consequences of such actions are to drive the low price up and the high price down until profitable arbitrage opportunities no longer remain.

The first line of defense of the Law of One Price is financial arbitrage, or what some observers refer to as trading in “paper oil.” If I simultaneously buy WTI futures and sell Brent futures, I can take my profit before anybody on the ground gets their hands dirty moving actual oil. Plenty of people make their living doing just this, and this is in fact what is usually responsible for keeping the relative prices in different markets instantaneously synchronized in response to news that arises anywhere in the world.

But for some reason, the folks who usually play this game have taken their marbles and gone home. Maybe they were burned by trying to maintain a tighter Brent-WTI spread than true physical arbitrage warrants given the changing supply conditions on the ground, maybe they ran into other financial constraints, or maybe something else in the market scared them off.

But that leaves lots of money on the table right now for physical arbitrage– buy the physical product where it is cheap and sell it where it is more expensive. The Oil Drum notes that the most efficient way to do this would be to start running the Seaway pipeline, which is currently delivering oil from the Gulf of Mexico to Oklahoma, in reverse. But it seems ConocoPhillips, part owner of the pipeline and of a refinery in Oklahoma, is not interested in that plan. As an integrated refiner and producer, it can take its profits either as refinery margin or producer-seller. Transporting oil out of the Midwest might leave it vulnerable to political criticism as domestic oil prices rise in response that it perhaps avoids by maintaining the status quo.

But there are lots of other arbitrage opportunities here for other players. It apparently costs $6 to ship a barrel from Cushing to the Gulf of Mexico by rail or $10 by truck, either of which sounds pretty tempting with a spread of $15 or more. More fundamentally, there are lots of other suppliers in the chain with an opportunity to make money in easier ways. Basically anybody further upstream currently feeding into the supply that ends up in Cushing has a strong incentive to be looking at a better place to sell their product, and given time, they’re surely going to do just that.

And I wouldn’t expect it to take a whole lot of time. Those physical adjustments are going to occur and the price differential between WTI and Brent is going to be reduced. That could take the form of an increase in the price of oil at Cushing, a decrease in the price of oil in Europe, or a combination of both.

Or, if significant threats to European oil supplies drive the price of Brent way up, the price of oil in the U.S. Midwest should increase even more than the price in Europe. And, it seems, today it did just that.

Leave a Reply