I know I’m asking for trouble here. Goodness, simply mention the yellow stuff and people go crazy. In an earlier post, I asked Is Gold Money? I answered “no.” To all those who were deeply wounded by this answer, I am truly sorry. But the answer is still “no.”

Of course, the answer depends in part on how “money” is defined. There are legal definitions, like “lawful tender” and “legal tender” (they are distinct). There are operational definitions, like M1 and M2. But the definition I used was an economic one. Money is an object that “circulates widely as a means of payment.” In the U.S. today, cash fits this description. So do the electronic digits sitting in your chequing account (so M1 fits).

But gold, in whatever form it takes, does not fit this description. Unlike government cash and bank digits verifiable by debit card, there is no standardized easily recognizable gold unit circulating widely as a payment instrument in the U.S. today. If you were to try to pay your groceries with gold coins, they might accept them, but at a huge discount. This discount reflects the illiquidity of gold. Gold is not money.

This is not to say that one should therefore not own gold. Even if gold is not money now, it may be one day in the future. And even if it is never money, it may still constitute a good store of value. Certainly, gold appears to be a better store of value than, say, the USD. The price of gold, measured in units of USD, has been rising over time. The purchasing power of the USD has been falling over time (inflation). So gold is a better store of value than the USD.

But so what? Who in their right mind stores value by tucking USD under their pillow? Cash is easily transformed into an interest-bearing asset, like a government or corporate bond. Or one could purchase a wide basket of equities, like the S&P500. The question I want to ask here is whether gold is a better store of value than one of these competing storage devices.

In what follows, I choose the S&P500 total return index (assumes that dividends are re-invested). The experiment is as follows. I am going to take four years: 1970, 1980, 1990, and 2000. For each of these years, I am going to imagine investing $1 in gold and $1 in the stock market. Then I’m going to track how well these two investments store value from the starting date to the present.

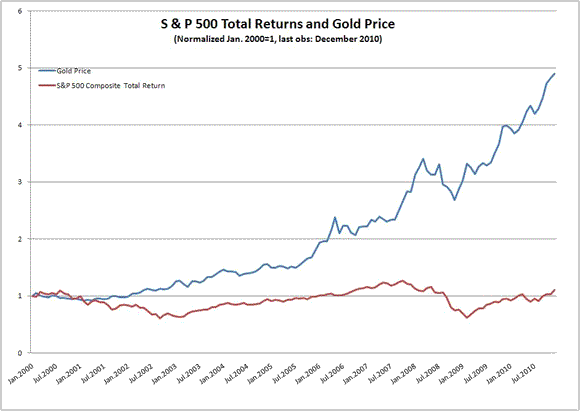

Returns since 2000

If you had invested $1 in gold in 2000, you would now be up almost 500%. In contrast, your investment in the S&P500 would have returned virtually zero. Gold appears to have an excellent store of value over the last decade.

Gold is frequently touted as a superior inflation hedge. Yet, the US inflation rate over the last decade was not very high. Nevertheless, gold kicked a$$, so to speak. Good for gold. Good for gold bugs.

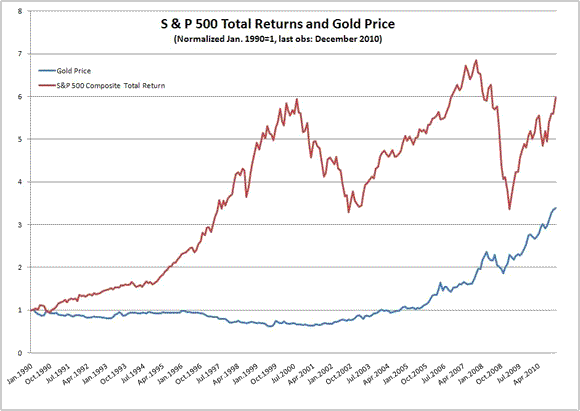

Returns since 1990

Whoa, this looks a little different, don’t it? If you had invested $1 in gold 20 years ago, you would have gone 15 years with negative to zero returns. A late sample rally makes your return look a little better, but over this longer sample period, the S&P500 kicks gold’s a$$. But maybe we just have to look at a longer time horizon…

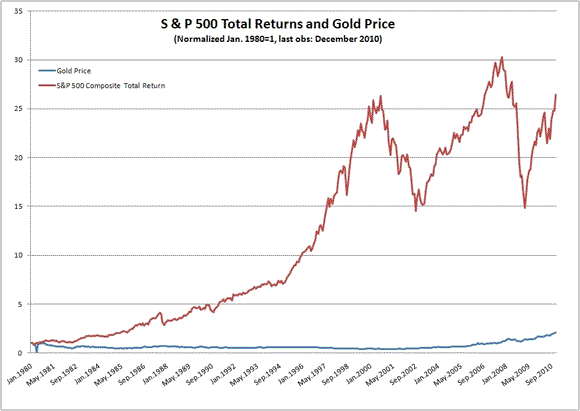

Returns since 1980

Oh, gosh. That didn’t work, did it? In fact, over 30 years, the relative return on gold looks absolutely horrible. Well, at least the return looks more stable, if that’s any consolation.

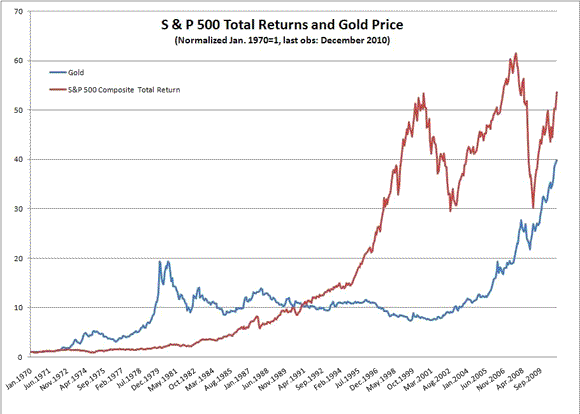

Return since 1970

Alright, we knew things had to get better for gold–and they did. The 1970s, a high-inflation episode, was a terrible decade for stocks and a very good one for gold. And it is the memory of this decade that remains burned in a gold bug’s brain.

And it’s a good lesson to have burned into one’s brain. It probably justifies holding some gold in a diversified portfolio of wealth. Can’t help but note, however, that even allowing for the disaster that was the 70s, the stock market still outperformed gold in the long-run. Something to keep in mind.

Leave a Reply