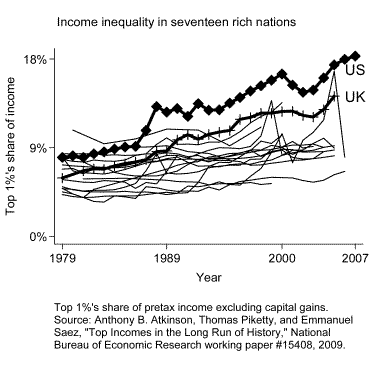

Income inequality has risen sharply in the United States and some other affluent countries since late 1970s, with much of the increase consisting of growing separation between the top 1% and the rest of the population.

Has this been bad for the incomes of the poor?

In a relative sense, the answer is yes, at least in the United States. According to the best available U.S. data, from the Congressional Budget Office, the share of income going to households at the bottom has decreased.

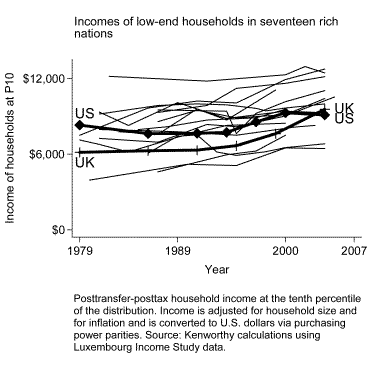

What about in an absolute sense? Would the incomes of low-end households have grown more rapidly in the absence of the top-heavy rise in inequality? If we look across the rich nations, it turns out that there is no relationship between changes in income inequality and changes in the absolute incomes of low-end households. The reason is that income growth for poor households has come almost entirely via increases in net government transfers, and the degree to which governments have increased transfers seems to have been unaffected by changes in income inequality. (For more detail, see my piece in the November-December issue of Challenge.)

In some countries with little or no rise in income inequality, such as Sweden, government transfers increased and so did the incomes of poor households. In others, such as Germany, transfers and the incomes of low-end households did not increase.

Among nations with sharp increases in top-heavy inequality, we observe a similar disjunction. Here the U.S. and the U.K. offer an especially revealing contrast. The top 1%’s income share soared in both countries, and through the mid-1990s poor households made little progress, as the following chart shows. But over the next decade low-end American households advanced only slightly, whereas their British counterparts experienced sizable gains. The New Labour governments under Tony Blair and Gordon Brown increased benefits and/or reduced taxes for low earners, single parents, and pensioners. As Jane Waldfogel documents in her book Britain’s War on Poverty, these were big policy shifts, even if not always high-profile ones. They produced a significant rise in the real disposable incomes of poor households.

Rising income inequality has a number of potential consequences — some of them, perhaps many, undesirable. Its apparent lack of impact on the absolute incomes of the poor over the past generation ought not lead us to overlook this. Still, it is noteworthy that some affluent countries have managed to engineer income growth for low-end households despite a significant top-heavy rise in inequality. For American policy makers, that might serve as welcome inspiration.

Leave a Reply