Under the threat of the financial crisis, US banks have received, without much controversy, huge bailouts. This column argues that the rescue plan ought to act as an automatic stabiliser, providing large bailouts to those institutions whose toxic assets turn out to be worth little and smaller bailouts to those whose toxic assets are worth more. But that is precisely what the Geithner Plan doesn’t do.

Under the threat of the present economic crisis, US financial institutions have received huge bailouts and guarantees. This support is leading to large increases in the national debt, which will need to be financed through taxes in the future. In the process, a massive redistribution of income is under way (Sachs 2009).

The public is vaguely aware of this redistribution and is angry about it. Why, people are asking, are we giving such generous payouts to the financiers who got us into this mess? How large might this redistribution turn out to be? Is this redistribution necessary to restore the financial industry to health?

These questions are tough to answer since the banks’ toxic assets, along with the resulting bailouts and guarantees, are fiendishly complicated and opaque. Not surprisingly, strategies that are complicated and misguided receive far less public scrutiny than those that are uncomplicated and misguided. This is one reason why the financial crisis was permitted to occur – the financial instruments were too complicated for their buyers, sellers, or regulators to understand. By the same token, the complexity of Geithner Plan also contributes greatly to its chances of political success, for now most voters don’t understand the terms of the bailout. (This, I will argue, is the strongest point in its favour.)

To grasp what is going on, let’s start with a simple question – what sort of policy do we need when the task is bailing out financial institutions with toxic assets? The distinguishing feature of toxic assets is that we don’t know how to value them. This lack of knowledge is what makes them “toxic.” This means that we don’t know in advance how large a bailout the institutions with toxic assets will need to enable them to survive.

To deal with this sort of a problem, needless to say, we need a policy that acts as an “automatic stabiliser” – institutions whose toxic assets turn out to be worthless will need larger bailouts than institutions whose toxic assets turn out to be valuable. Consider an analogy. We don’t know what the external temperature will be when we install a heating system in our house. And we don’t need to know, provided that we have a thermostat, so that the internal temperature adjusts automatically to whatever the external temperature happens to be. Along the same lines, we now need a financial rescue package that automatically adjusts to the problem at hand.

The Geithner Plan pretends to be an automatic stabiliser. The official line, after all, is that the plan permits the free market system to price the toxic assets, and thereby enables the government to provide the appropriate amount of bailout. As we will see in a moment, the truth looks different. The Geithner Plan is more like a thermostat that is stuck at one temperature, so that we might freeze in the winter, but boil in the summer. Specifically, I will show that the plan can be fabulously wasteful when the banks need only modest bailouts. Then far too much money may be redistributed from the taxpayer to the financial sector. And when the banks need big bailouts, the plan may turn out to be completely ineffective. In short, this is precisely the sort of policy we want to avoid when we are faced with toxic assets.

A frightening scenario

To see why this is so, let’s take a simple example (for more, see Krugman 2009, Stiglitz 2009, and Young 2009). Consider an asset that has a 50% chance of being worth $100 and a 50% chance of being worthless. So the asset’s value is $50, the average of $100 and $0. (I leave you to add enough zeros to each dollar figure so that the example looks realistic to you.) Suppose that the asset is toxic, which means that we don’t yet know how to value it, since we aren’t yet aware that the asset has a 50-50 chance of yielding $100 or $0.

Now let’s work out how US Treasury Secretary Geithner’s plan would deal with this asset, and how much income would be redistributed in the process. Although the arithmetic is boring, I assure you that the outcome of our calculations won’t be. They show that there is something fundamentally wrong with the Geithner Plan – it generates a potentially gigantic amount of redistribution and, furthermore, the redistribution is completely unnecessary, since it is completely irrelevant to the job of bailing out the banks.

To keep my explanation simple, I will assume, in agreement with the Geithner Plan, that the right way to deal with the financial institutions that are too-large-to-fail is to bail them out with taxpayers’ money. Then all I will ask is whether the plan gives them the bailouts they need. (As a matter of fact, however, I think this assumption is wrong. In my opinion, (i) the burden of bailout out these institutions should be shared among the taxpayer, the bondholders, and the stockholders of these institutions and (ii) the appropriate instrument is debt-for-equity swaps. They, incidentally, could be made to work as an automatic stabiliser, but that is a different story.)

Since the asset is toxic, its current valuation is inevitably somewhat arbitrary. So suppose that the bank currently values the asset at $55 – which is $5 more than the asset is actually worth – and if the bank were to receive $55, it would return to financial health. Moreover, suppose that a private-sector bidder indeed offers $55.

Under the Geithner plan, the government finances 92% of the asset, the private bidder finances the remaining 8%, and the private bidder and government each receive the same amount of equity. If the asset costs $55, then the private bidder contributes $4.4 in equity (8% of $55). The government also contributes $4.4 in equity. So the government loan is $46.2 ($55 – $4.4 – $4.4).

Recall that the asset has a 50% chance of being worth $100. If that happens, then the government loan can be repaid. The remaining profit is $53.8 (which is $100 minus the loan of $46.2). Since the private bidder and government have the same amount of equity, this profit gets shared equally between them. So each gets $26.9. The private bidder’s yield is $22.5 (which is $26.9 minus the $4.4 that the private bidder paid for the asset).

The asset also has a 50% chance of being worth $0, and if that happens, then the government loan can’t be repaid. So the private sector loses $4.4 (its equity stake) and government loses $50.6 (its loan of $46.2 plus its equity stake of $4.4).

Let’s take stock. On average, the private sector’s gain is $9.05 (which is the average of its $22.5 gain in good times and the $4.4 loss in bad times). So the private bidder winds up with the fabulous rate of return of 205.68 % (namely, its $22.5 average gain relative to its initial investment of $4.4)!

But the government, on average, makes a loss of $14.05 (which is its $22.5 gain in good times and its $50.6 loss in bad times). This means that the government is left with a horrifying rate of return of -319.32 % (namely, its average loss of $14.05 relative to its initial investment of $4.4)!

Observe that the government’s average loss ($14.05) is higher than the private sector’s average gain ($9.05); the government and private sector together make a loss of $5. This is the amount they overpaid for the asset.

It’s now easy to see what redistribution has taken place. $5 gets redistributed from the private bidder to the bank (since the bidder paid $55 for an asset worth $50) and $9.05 gets redistributed from the taxpayer to the private bidder.

The really sad thing is that only the first payment is necessary if we wish to return the bank to health through a bailout. But under the Geithner plan, the taxpayer winds up paying $14.05. That is 181% more than was needed to save the bank!

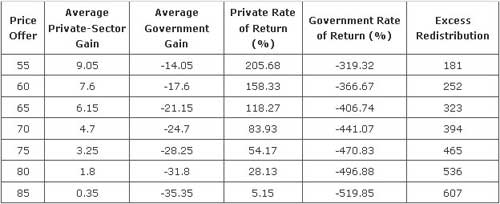

But that, unfortunately, is not the end of the story. Since the private-sector bidder made a rate of return of 205.68 % on his equity investment, the other bidders may be expected to bid up the price of the asset. The following table shows what will happen.

Table 1. Private sector bidding scenarios

As the price of the asset is bid up (from $55 to $60 to $70), the private-sector rate of return gradually falls (from 205.68% to 158.33% to 118.27%…). Eventually, once the offer price has reached $85, this rate of return has declined to 5.15%. At this point, there is little to be gained from bidding the price up further and so the price of the asset may be expected stabilise at around $85.

At this price, as you can see, the government’s rate of return is an eye-popping -519.85%. Now $35 gets redistributed from the taxpayer to the bankers (since $85 was paid for an asset worth $50) and $0.35 gets redistributed from the taxpayer to the private-sector bidder.

But since the bank just needed $5 to be restored to health, the taxpayer is paying in excess of 600% more than is required.

Other frightening scenarios

The exercise above is just one of many possible frightening possibilities. So far our calculations were based on the premise that only $5 – the equivalent of 10% of the true value of the bank’s toxic assets – is required to save the bank. But suppose that more money were required, say 20% or more of the value of the toxic assets. How would the Geithner Plan perform then?

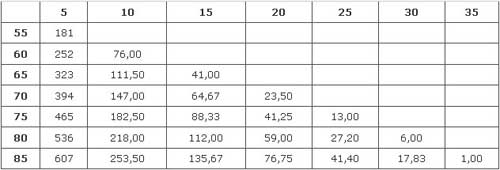

The next table shows the amounts of excess redistribution corresponding to different amounts of bailout.

Table 2. Excess redistribution for different bailouts

The numbers in the first row are the size of the bailout. So if a bailout of $10 is required (which is 20% of the true value of the toxic asset), then the bank will accept at least $60 for the asset and thus the excess redistribution is 76%. But, as we saw in the previous table, the private rate of return is high and so the price of the asset will get bid up to $85, corresponding to excess redistribution of about 135%.

In this way, the table shows clearly that as the size of the required bailout rises, so the amount of excess redistribution falls. If it should turn out – by coincidence – that the required size of the bailout ($35) is about equal to the amount by which the Geithner Plan induces the private bidders to overpay for the asset ($85 – $50 = $35), then there will be virtually no excess redistribution. But this, as noted, could only happen by accident.

But what happens if even an overpayment of $35 – corresponding to 70% of the true value of the toxic asset – is insufficient to return the bank to health? Specifically, suppose that $40 (amounting to 80% of the value of the toxic asset) is required. What then? The first table gives the answer. At $40 overpayment, the asset must be valued at $90, and then the private rate of return would be about -15%, that is, the private bidders would be making a loss. So clearly no private bidders would be willing to offer $90. This means that the Geithner Plan would not work, since the banks would require an overpayment in excess of what the bidders would be willing to offer. There would be no takers, and the government’s offered loan would remain unused. Then, in the absence of any further rescue package, the bank would have to default.

What is the upshot of this woeful portfolio of frightening scenarios? Which one is likely to apply? The answer is as simple as it is important. We don’t know. It’s the essence of a toxic asset that we don’t know. If we knew what the asset was worth, it wouldn’t be toxic. If we knew how large a bailout each financial institutions needs, the policy response would hardly be a challenge.

It is for this reason that we need a rescue plan that acts as an automatic stabiliser, providing large bailouts to those institutions whose toxic assets turn out to be worth little and smaller bailouts to those whose toxic assets are worth more. But that is precisely what the Geithner Plan doesn’t do. As the exercise above shows, far too much money is transferred from the taxpayer to the banks when these banks need only modest bailouts, whereas none might be transferred when they need large bailouts. Only through a massive coincidence could it happen that the plan transfers the right amount of equity to the banks.

In short, this is a hopeless plan. Of course, it’s true that some of the redistributed money will probably make its way back to the taxpayer through pension funds, mutual funds, and other institutions that invest in the financial sector. But is this redistribution sensible? Do we want to take potentially huge amounts of money from the taxpayer and give them to the financiers, just as the economy slides deeper and deeper into recession? Do we want to rely on a policy that we know will become ineffective as soon as the banks are in really big trouble?

I find it hard to believe that the American public would have accepted the Geithner plan if these possibilities had been presented to them. No, I think that the main appeal of the plan lies in its complexity, enabling voters to retain the hope – for the time being – that the banks will get the funds they need through the capitalist system, free of government control.

References

Krugman, Paul (2009). “Geithner plan arithmetic” 23 March.

Sachs, Jeffrey (2009). “Will Geithner and Summers Succeed in Raiding the FDIC and Fed?” VoxEU.org, 25 March.

Stiglitz, Joseph (2009). “Obama’s Ersatz Capitalism” New York Times, 31 March.

Young, Peyton (2009). “Why Geithner’s plan is the taxpayers’ curse” Financial Times, 1 April.

![]()

Leave a Reply