Call me a sucker for the classics. Be it the original trilogy, the old Kenner figures, the “Nyub Nyub” song at the end of Jedi, or the classic theories of exchange rates. While the old classics, like interest rate parity or purchasing power parity, may not exactly fit reality (especially not in real time), I think the concepts remain useful. That is to say that as inflation rises, a nation’s currency should depreciate. As interest rates fall, suggesting that there are few good local investment opportunities, the currency should similarly depreciate.

I wrote several weeks ago that the dollar should depreciate for exactly those reasons (I even made the same classics joke). The U.S. should have higher relative inflation vs. other countries, and the Fed would likely hold U.S. short-term rates lower than other countries.

A corollary to the above discussion would suggest that bond yields should normally be inverse correlated to the dollar. If the dollar is falling because inflation is rising, that should also be reflected in higher bond yields.

Or if you want to make a deficit-based argument for a weaker dollar, to which I don’t ascribe, but either way, it would still suggest that weaker dollar = higher bond yields. If the deficit is causing a flight from U.S. assets, then Treasury prices should fall as money flows out of the U.S.

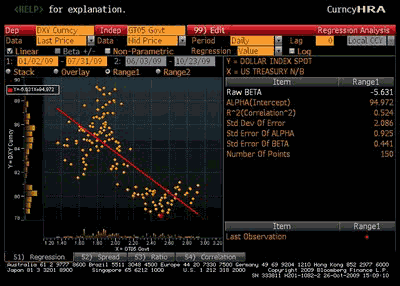

Indeed, that is exactly the pattern you saw for the first half of this year.

Lower dollar coincided with higher bond yields. Exactly what we’d expect.

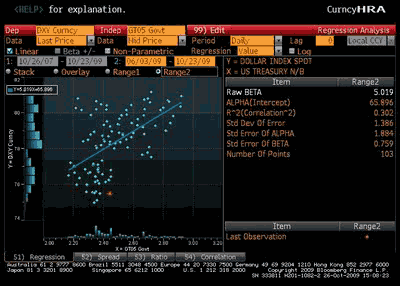

But then a funny thing happened on the way back to normal. Like Zam Wessel, The dollar/bond relationship went completely the other way.

What’s going on here? The dollar gets weaker, bond yields fall?

It traces back to why the dollar is falling. Unfortunately we’re going to have to get away from the classics and consider what’s going on right now. Right now, the U.S. is the cheapest place to borrow money anywhere in the world. If you are a non-dollar entity, whether you are a government, central bank, insurance company, etc., your cheapest source of funds is anything U.S. LIBOR-based. You can borrow in dollars and re-invest in something local to you. That’s dollars flowing out of the U.S., thus pushing the dollar weaker.

Meanwhile if you are a U.S.-based investor, your cheapest source of funding is still something U.S. LIBOR-based. Remember that banks are still sitting on huge deposit bases and are either unwilling to lend or unable to find worthy borrowers who want credit. What do they do with their deposit base? Invest it in bonds! If your borrowing cost from the Fed is 0.12% (approximately where Fed Funds is trading), you can buy 2-year notes at 1% and make tremendous carry. Just take a gander at the recent bank earnings. The NIM’s are huge.

When is the Fed going to take away the bowl of Aunt Beru’s famous blue milky looking punch? According to a recent story from the Financial Times, maybe sooner than we think. I had long thought that a Fed hike was a long way away but as consumer spending starts rising, the risk of inflation returns. Now it seems like some number other than zero is probably the appropriate funds rate.

Plus it would be nice to think that the Fed realizes how zero Fed Funds is impacting financial markets and the potential, potential mind you, for it to create dangerous distortions. Whether they actually do realize this or not is any one’s guess.

- Bulenox: Get 45% to 91% OFF ... Use Discount Code: UNO

- Risk Our Money Not Yours | Get 50% to 90% OFF ... Use Discount Code: MMBVBKSM

Disclaimer: This page contains affiliate links. If you choose to make a purchase after clicking a link, we may receive a commission at no additional cost to you. Thank you for your support!

Really good assessment on yield conundrum. However, bad debt would need to be written down (by way of BK’s and liquidations) prior to rates moving up. This is because banks do not want to lend due to high debt loads and would continue buying bonds and thereby pushing or keeping rate low. In addition, the fed also participates in the purchase of long term bonds in efforts to encourage more borrowing (this is like trying to force feed more debt in an already debt saturated system) and thereby you have a bond bubble just waiting to crash.

Also, the current run up in equities can be contributed to this due to liquidity desperately searching for higher rates of return and currency depreciation (both due to the lower yields). Dollar strength may be an indicator of a change in the tide, at least temporarily. The issue remains that bad debt MUST be written off on a large scale prior to recovery.