I valued Amazon (NASDAQ:AMZN) for the first time in 1998, as an online book retailer, and much of what I know about valuing young companies today came from the struggles I went through, modifying what I knew in conventional valuation, for the special challenges of valuing a company with no history, no financials and no peer group. Out of that experience was born a paper on valuing young companies, which is still on my website and the first edition of the Dark Side of Valuation, and if you want to see some horrendously wrong forecasts, at least in hindsight, you can check out my valuation of Amazon in that edition.

While I had a tough time justifying Amazon’s valuation, in its dot-com days, I always admired the company and the way it was managed. When I was put off balance by an Amazon product, service or corporate announcement, I re-read Jeff Bezos’ letter to Amazon shareholders from 1997, because it helped me understand (though not always agree with) how Amazon views the business world. In that letter, Bezos laid out what I called the Field of Dreams story, telling his stockholders that if Amazon built it (revenues), they (the profits and cash flows) would come. In all my years looking at companies, I have never seen a CEO stay so true to a narrative and act as consistently as Amazon has, and it is, in my view, the biggest reason for its market success.

I have valued Amazon about once a year every year over its existence, and I have bought Amazon four times and sold it four times in that period. That said, there are two confessions that I have to make. The first is that I have not owned Amazon since 2012, and have thus missed out on its bull run since then. Second, through all of this time, I have consistently under estimated not only the innovative genius of this company, but also its (and its investors’) patience. In fact, there have been occasions when I have wondered, staying true to my Field of Dreams theme, whether Shoeless Joe would ever make his appearance.

Amazon’s Market Cap Rise

Amazon’s rise in market capitalization has had more ups and downs than either Google or Facebook, but it has been just as impressive, partly because the company came back from a near death experience after the dot-com bust in 2001.

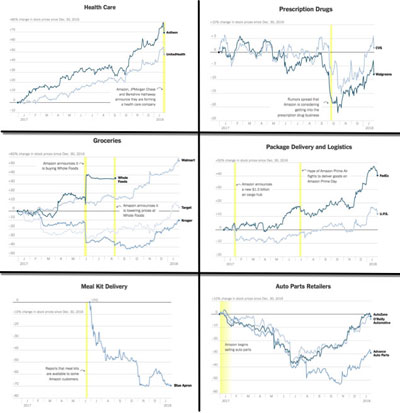

The more remarkable feature of Amazon’s rise has been the debris it has left in its wake, first with brick and mortar retail in the United States, but more recently in almost every business it has entered, from grocery retail to logistics. These graphs, excerpted from a New York Times article earlier this year, tells the story:

I know that this picture is probably is too compressed for you to read, but suffice to say that no company, no matter how large or established it is is safe, when Amazon enters it’s market. Thus, while you can explain away the implosion of Blue Apron, when Amazon entered the meal delivery business, by pointing to its small size and lack of capital, note that the decline in market value at Kroger, Walmart and Target on the date of the Whole Foods acquisition was vastly greater in dollar value terms, and these firms are large and well capitalized. It is also worth noting that the decline in market cap is not permanent and that firms in some of the sectors see a bounce back in the subsequent time periods but generally not to pre-Amazon entry levels. If Amazon represents the light side of disruption, the destruction of the status quo and everything associated with it, in the businesses that it enters, is the dark side.

Amazon: Operating History and Model

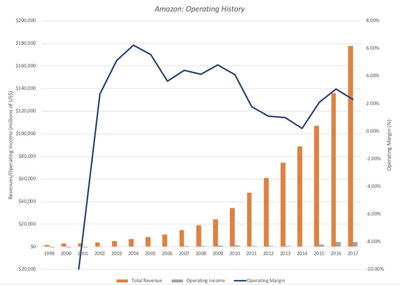

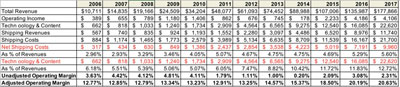

Rather than provide an involved explanation for why I call Amazon a Field of Dreams company, I will begin with a chart of Amazon’s revenues and operating income that will explain it far more succinctly and better:

Amazon has clearly delivered on revenue growth, as its revenues have gone from $1.6 billion in 1999 to $177 billion in 2017, but its margins, after an initial improvement, went through an extended period of decline. In most companies, this would be viewed as a sign of a weak business model, but in the case of Amazon, it is a feature of how they do business, not a bug. In effect, Amazon has extended its revenue growth by expanding into new businesses, often selling its products (Kindle, Fire, Prime) at or below cost. That, by itself, is not unique to Amazon, but what makes it different is that it has been able to get the market to go along with its “if we build it, they will come” strategy.

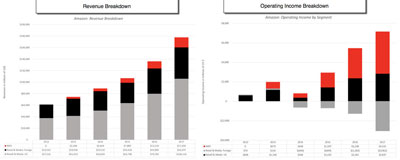

The mild uptick in profitability in the last three years has been fueled by Amazon’s web services (AWS) business, offering cloud and other internet related services to other businesses, and that can be seen in the graph below, showing revenues and operating profits broken down by segment:

Over the last five years. AWS has accounted for an increasing slice of revenues for Amazon, but it is still small, accounting for 10% of all revenues in 2017. On operating income, though, it has had a much bigger impact, accounting for all of Amazon’s profitability in 2017, with AWS generating $4,331 million in operating profits and the rest of Amazon, reporting an operating loss of $225 million.

To back up my earlier claim that Amazon’s low profits are by design, and not an accident, let’s look at two expenses that Amazon has incurred over this period that are treated as operating expenses, and are reducing operating profit for the company, but are clearly designed as investments for the future. The first is in technology and content, which include the investments in technology that are driving the growth in the AWS business and content, for the media business. The second is in net shipping costs, the difference between what Amazon collects in shipping fees from its customers and what it pays out, which can be viewed as the investment is making in building up Amazon Prime.

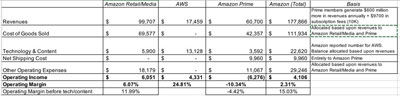

Not only are the technology/content and net shipping costs a large portion of overall expenses, amounting to 18.32% of revenues in 2017, but they have increased over time. The operating margin for Amazon would have been over 20%, if it had not incurred these expenditures, but with those higher, the company would have had far less revenues, no AWS business and no Amazon Prime today. To value Amazon today, I think it makes sense to break it up into at least three parts, with the first being its retail/media business globally, the second its AWS business and finally, Amazon Prime. In the table below, I attempt to deconstruct Amazon’s numbers to estimate how much each of these arms is generated as revenues and created in operating expenses in 2017, as a prelude to valuing them.

Note that I had to make some estimates and judgment calls in allocating revenues to Amazon Prime, where I have counted only the incremental revenues from Amazon Prime members, and in allocating content costs. For Amazon Prime, for instance, I have used an assumption that Prime members spend $600 more than non-Prime members, to estimate incremental revenues, and added the $9.7 billion in subscription premiums that Amazon reported in 2017. The net shipping costs have been fully allocated to Amazon Prime and all of the operating expenses that Amazon reported for AWS are assumed to be technology and content. The remaining expenses are allocated across AWS and Amazon Retail/Media, in proportion to their revenues. In my judgment, both Amazon Retail/Media and AWS generated operating profits in 2017, but the latter was much more profitable, with a pre-tax operating margin of 24.81%. Amazon Prime was a money loser in 2017, but its margins are less negative than they used to be, and at 100 million members, it may be poised to turn the corner.

Amazon Business Model

If there are any secrets in Amazon’s business model, they are dispensed when you read Amazon’s 10K, which is remarkably forthcoming about how the company approaches business. In particular, the company emphasizes three key elements in its business model:

- Focus on Free Cash Flow: I tend to be cynical when companies talk about free cash flows, since most use self serving definitions, where they add “stuff” to earnings to make their cash flows look more positive. Amazon does not seem to take the same tack. In fact, it not only nets out capital expenditures and working capital needs, as it should, but it even nets out acquisitions (such as the $13.2 billion it spent on Whole Foods) to get to free cash flow.

- Manage working capital investment: Perhaps remembering times as a start-up when mismanaging inventory brought it to its knees, the company is focused on keeping its investment in working capital as low as possible, though that does sometimes involve strong arming suppliers.

- Use Operating leverage: Amazon is clearly conscious about its cost structure, recognizing that its revenue growth can give it significant advantages of economies of scale, when it comes to fixed costs.

There are two additional features to the company that I would add, from my years observing the company.

- Patience: I have never seen a company show as much patience with its investments as Amazon has, and while there are some who would argue that this is because of it’s large size and access to capital, Amazon was willing to wait for long periods, even when it was a small company, facing a capital crunch. I believe that patience is embedded in the company’s DNA and that the Bezos letter in 1997 explains why.

- Experimentation: In almost every business that Amazon enters, it has been willing to try new things to shake up the status quo, and to abandon experiments that do not work in favor of experiments that do.

There is no scarier vision for a company than news that Amazon has entered its business. If you are in that besieged company, how do you survive the Amazon onslaught? We know what does not work:

- Imitation: You cannot out-Amazon Amazon, by trying to sell below cost and wait patiently. Even if you are a company with deep pockets, Amazon can out-wait you, since it is not only how they do business and they have investors who have accepted them on their terms.

- Cost Cutting: There are companies, especially in the US brick and mortar retail space, that thought they could cut costs, sell products at Amazon-level prices and survive. By doing so, they speeded their decline, since the poorer service and limited inventory that followed alienated their core customers, who left them for Amazon.

- Whining: Companies under the Amazon threat often resort to whining not only about fairness (and how Amazon breaks the rules) but also about how society overall will pay a price for Amazon domination. There are seeds of truth in both argument, but they will neither slow nor stop Amazon from continuing to put them out of business.

While there is no one template for what works, here are some strategies, drawn from looking at companies that have survived Amazon, that improve your odds:

- Tilt the game: You can try to get governments and regulators to buy into your warnings of monopoly power and societal demise and to regulate or restrict Amazon in ways that allow you to continue in business.

- Play to your strengths: If you have succeeded as a company before Amazon came into your business, you had competitive advantages and core customers who generated that success. Nourishing your competitive advantages and bringing your core customers even closer to you is key to survival, but that will require that you live through some financial pain (in the form of higher costs).

- And to Amazon’s weaknesses: Amazon’s favored markets have high growth and low capital intensity, and when they get drawn into markets that demand more capital investment, like logistics, it is because they were forced into them. If you can move the terrain to lower growth, higher capital intensity businesses, you can improve your odds of surviving Amazon.

None of these choices will guarantee success or even survival, and there are times where you may have to seek partnerships and joint ventures to make it through, and if all else fails, you can try some witchcraft.

Valuing Amazon Stock

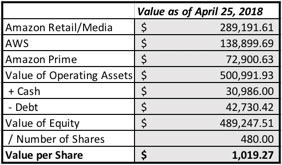

In my prior iterations, I tried to value Amazon as a consolidated company, arguing that it was predominantly a retail company with some media businesses. The growth of AWS and the substantial spending on Amazon Prime has led me to conclude that a more prudent path is to value Amazon in pieces, with Amazon Retail/Media, AWS and Amazon Prime, each considered separately.

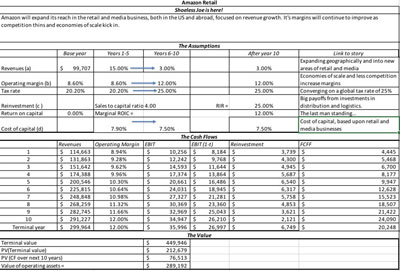

1. Amazon Retail/Media

To value the heart of Amazon, which still remains its retail and media business, I used the revenues and operating margin that I estimated based upon my allocation at the end of the last section as my starting point, and assumed that Amazon will be able to continue growing revenues at 15% a year for the next five years, while also improving its operating margin (currently 9.09%, with technology and content costs capitalized) to 12%. The revenue growth assumption is built on Amazon’s track record of being able to grow and the improved margin reflect expected economies of scale. The resulting value is shown below:

Based upon my assumptions, the value that I attach to the retail/media business is about $289 billion. The key driver of value is the operating margin improvement, built into the story.

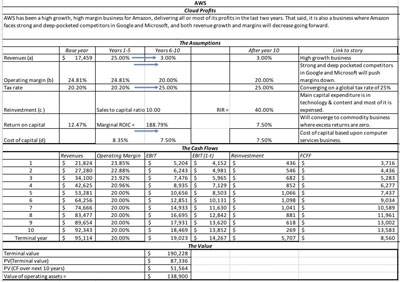

2. AWS

If Amazon’s reported numbers are right, this division is the profit machine for the company, generating an operating margin of close to 25%, while revenues grew 42.88% in 2017. While I believe that this business will stay high growth and profitable, it is also one where Amazon faces strong competitors in Microsoft and Google, just to name two, and both revenue growth rates and margins will come under pressure. I assume revenue growth of 25% a year for the next 5 years, with operating margin declining to 20% over that period. The value is shown below:

The value that I estimate for AWS is about $139 billion. The key for value creation is finding a mix of revenue growth and operating margin that keeps value up, since going for higher growth with much lower margins will cause value to dissipate.

3. Amazon Prime

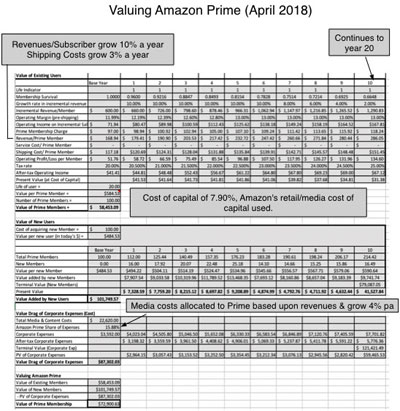

To value Amazon Prime, I use the same technique that I used last year to value it, starting with a value of a Prime member, and building up to the value of Prime, by forecasting growth in Prime membership and corporate costs (mostly content). I updated the Prime membership number to 100 million (from the 85 million that I used last August) and used the 2017 financial statements to get more specific on both content costs and on the cost of capital. The value is shown below:

Based upon the layers of assumptions that I have made, especially on shipping costs growing at a rate lower than membership rolls, the value that I estimate for Amazon Prime is about $73 billion. The key input here is shipping costs, since failing to keep it in control will cause the value to very quickly spiral down to zero.

Amazon, the Company

With all three pieces completed, I bring them together in my valuation of the company, incorporating the total debt outstanding in the company of $42,730 (including capitalized operating leases) and cash of $30.986 million, to arrive at a value per share of $1019.

At $1,460/share, on April 25, the stock is clearly out of my reach right now. Given that I have not been able to justify buying the stock at any time in the last five years, as it rose from $250/share to $1500, my suggestion is that you do you don’t take my word, and that you make your own judgment. You can download the spreadsheets that I have for Amazon Retail/Media, AWS and Amazon Prime at the end of this post, and change those assumptions of mine that you think are wrong.

Investment Judgment

The FANG stocks represent great companies, but of the four, I think that Amazon has the most fearsome business model, simply because its platform of disruption and patience can be extended to almost any other business, one reason why every company should view Amazon as a potential competitor. I know that the old value adage is that if you buy quality companies and hold them forever, they will pay for themselves, but I don’t believe that! There are good companies that can be bad investments and bad companies that can be terrific investments, as I noted in this post. Amazon has fallen into the first category for much of the last five years and continues to do so, at today’s market price. But good things come to those who wait, and I know that there be a time and a price at which it will be back in my portfolio.

Comprehensive and very good write-up on AMZN.

The comments section affords an opportunity to express my views, largely unrelated to AMZN, for readers (non-institution).

To invest in AMZN, Google, CISCO etc when they were in nascent stage, one has to have crystal ball. This idea is not feasible.

Aim is to generate profit in the stock market. Buy and Hold strategy propagated by Warren Buffet does not work out in today’s rapid changing environment. Five years ago, artificial intelligence was not a popular concept. Today it borders on dominance. One may hold a stock for a few months to couple of years maximum. If financial parameters are liked and stock is hovering around 52 week low, Sell the Put Option at a price lower than market price or buy the stock outright. That is it. Take a vacation. You deserve after all.

Rakesh Lakhotia