CRISPR (short for Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeat) can’t seem to stop being in the news as each day brings new developments that expand CRISPR’s capabilities. CRISPR is a defense system used by bacteria to help repel attacking viruses called bacteriophage. In 2012, this defense system was turned by scientists into a gene-editing tool.

CRISPR-Cas9 is currently the most widely used version of CRISPR. But just recently, a new variant has been added to its toolbox — CRISPR-Cpf1 — which scientists demonstrated could correct mutations that cause a condition called Duchenne muscular dystrophy which affects heart muscles and eventually ends up in heart failure.

Prior to that, researchers led by one of the pioneers of CRISPR showed how they were able to turn this gene-editing technology into a diagnostic tool for detecting pathogen-caused diseases and cancer-causing mutations.

The latest news about CRISPR involves turning it into something like an antibiotic treatment — to “specifically kill your bacteria of choice,” as food science professor Jan-Peter Van Pijkeren of the University of Wisconsin-Madison puts it. And its first target is Clostridium difficile (C. difficile) — a bacterium that causes life-threatening diarrhea and colon inflammation, and mostly affects hospitalized patients or those who recently received medical care, including antibiotic treatments. C. difficile also happens to be one of the three antibiotic-resistant threats classified by the CDC as urgent, which basically means it requires high priority attention.

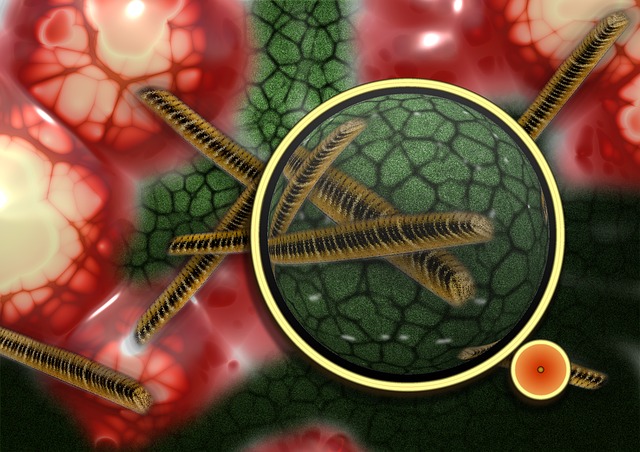

The plan is simple: develop bacteriophage that will deliver a customized CRISPR message instructing C. difficile to commit suicide.

In their natural form, stomach acid will quickly break down bacteriophage. But when mixed with a special probiotic (whether in liquid form or as a pill), the bacteriophage can sneak in to a person’s intestinal tract, deliver its message to nearby C. difficile, and cause them to self-destruct.

The beauty of using CRISPR is that it can be very specific. It can just target the species of bacteria that it’s supposed to kill and leave all other bacteria, including the beneficial ones, unharmed.

This is what will differentiate it from conventional antibiotics which kill good and bad bacteria alike, and is exactly what leads to antibiotic resistance in the first place.

According to Professor Van Pijkeren, the probiotic they are developing is still in its early stages and has yet to be tested in animals. But the prospects look promising, especially since similar research has already shown that CRISPR delivered via bacteriophage can kill bacteria effectively. In fact, some companies have already began working on CRISPR-based antibiotics for commercial use.

The initiative to develop alternative methods of fighting bacteria is something the world badly needs, in light of the growing threat of superbugs and antibiotic resistance. And using probiotics adds a twist of bittersweet irony to it — using ‘good’ bacteria to tell ‘bad’ bacteria to mess with their own DNA and ultimately kill themselves.

As Professor Van Pijkeren explained in an article that came out of the University of Wisconsin-Madison newsroom : “I think it’s pretty fascinating tha[t] an organism like Lactobacillus in such low numbers and small amounts can actually have a health benefit. To then exploit these microbes to deliver therapeutics is very appealing because we know humans have been safely consuming them for thousands of years.”

Leave a Reply