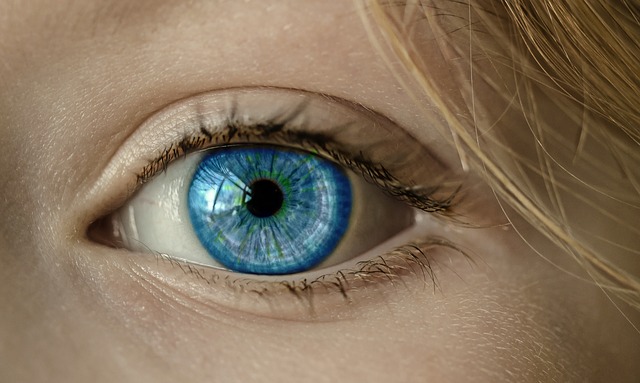

There have been many attempts to restore some degree of vision to people suffering from retinal degeneration — a condition in which light-sensitive cells in the retina (called photoreceptor cells) deteriorate, and can eventually lead to blindness.

Some methods are biological in nature, such as engineering of genes to repair mutations that result in blindness. Others have turned to electronics, like bionic eye devices that make use of an external camera to transmit signals that activate nerves. The latest addition to this growing list is somewhat of a hybrid — biological and electronic at the same time — a retinal implant developed by a research team from the Italian Institute of Technology.

As its name implies, the implant was designed as replacement for a damaged retina. It is made of a thin layer of conductive polymer, placed on top of a silk-based substrate, and covered with a semiconducting polymer that serves a photovoltaic function — absorbing light as it enters the eye. After light is absorbed, electricity is used to stimulate retinal neurons into filling in the gap left by the eye’s natural photoreceptor cells.

To check if the device works, the team used mice as their test subjects. They implanted the artificial retinas into the eyes of rats specifically bred to develop some form of retinal degeneration. Thirty days later, when the implants had already healed, the team tested the rats’ sensitivity to light.

What they found was that in low light, the implants didn’t seem to have any effect. But in brighter light, the rats’ response was almost comparable to that of a healthy animal. Specifically, when the treated rats were exposed to light that was about 4 – 5 lux bright, their pupils closed as strongly as how the pupils of healthy rats did. And because the implants were made with organic-friendly materials, the effect remained the same even after 6 – 10 months, with no issue of tissue inflammation.

Further tests — such as implanting only one retina instead of two — showed that the implant was capable of stimulating and activating the brain’s visual cortex, that part of the brain which lets you know what you are seeing.

Based on the tests they conducted, the team is certain that their prosthetic retina is working. The thing is, they’re not exactly sure how it’s working, particularly how the electric impulses generated by the photovoltaic polymer stimulated nerve activity. Plus, there’s also the issue on how to tell for certain that the rats’ vision got restored somehow. We can’t ask the rats, right?

In spite of these initial ‘stumbling blocks’, there are more reasons to go forward than backward. More tests can always be done to validate whether the results are real or just a fluke.

The team is planning on conducting preliminary human trials in the second half of this year. Which means by next year, we may already know for sure if these implants actually work.

The research has been published in Nature Materials.

Leave a Reply