In my previous blog post I criticized the latest annual BIS report on several grounds. One of them was their analysis of monetary policy. Let me extend some of the arguments I made yesterday because I see the same inconsistencies (and errors) being brought up by others.

I find it surprising that those who argued that QE had very little effect in the economy are now ready to blame the central bank for all the damage they will do to the economy when they undo those measures. So they seem to have a model of the effectiveness of central banks that is very asymmetric – I would like to see that model. It is also surprising that those who express concern about the excessive expansionary nature of monetary policy do not bother comparing the performance of inflation against its target. Shouldn’t we measure output and performance when judging central banks?

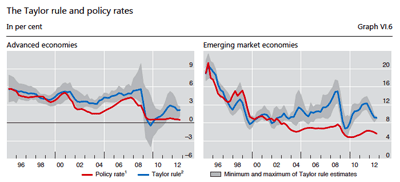

Let me bring back a chart from the BIS report that I included yesterday in my post, the one where they compare interest rates in advanced and emerging economies against what the Taylor rule would suggest.

(click to enlarge)

The blue line represents interest rates as suggested by the Taylor rule. The grey area represents some uncertainty around how this rule should be formulated. The red line is the actual interest rate set by central banks. Since 2002 the red line is below the blue line almost every year (with the exception of the Fall of 2008 in advanced economies). In some cases the distance is large (as many as four percentage points). The BIS report concludes that central banks are playing with fire, that they are setting interest rates too low and that this can be a source of inflation and/or asset bubbles.

But how can it be that central banks get the interest rate wrong for more than a decade always in the same direction and inflation remains within its target? What economic model can generate that behavior of inflation? How can it be that central banks are so powerless at controlling inflation? And if they are, why do we worry about these interest rates? Some will respond to these questions by arguing that we have seen inflation in some of these countries but it is a different type of inflation: asset price inflation. I have two responses for that:

1. I do not know of any macroeconomic model where expansionary monetary policy does not generate inflation defined as the increase in the prices of goods and services. While I am willing to accept that central banks might influence asset prices via their communications, I still have a problem with the way the Taylor rule is calculated above. The Taylor rule was originally designed and has been used later as a way to think about a benchmark to stabilize inflation (in goods and services(. If it is not playing any role anymore then we need to produce a new framework (theory) that explains why monetary policy does not affect inflation anymore, we need a new Taylor rule.

2. While it is true that we have witnessed some crazy behavior in financial markets over the last two cycles, the correlation with the way monetary policy has been conducted is weak. I participated in a study at the IMF in 2009 (part of their World Economic Outlook, see the chapter here) where we studied whether there was evidence that countries where monetary policy was more expansionary according to a Taylor rule (and other rules) saw bigger asset price bubbles. The evidence showed that the correlation was weak or inexistent. So there is limited evidence that monetary policy is the cause of the volatility we have seen in asset prices in the last two cycles. [Interestingly, I must admit that when I started the project I had very strong priors that we would find some strong evidence that monetary policy was behind bubbles in advanced economies. But the evidence was not there, so I changed my mind.]

Leave a Reply