I really dislike fawning Keynesians because I used to be one when I was a TA for Hyman Minsky back in college (he was a Post-Keynesian). As such I was amored with Keynes, and read many biographies about him. There’s no greater ire than that of early infatuations, in part because we feel tricked, and these objects remind us of a naive earlier self that wasted part of our precious finite life on a wrong road. Anyway, I can’t can read the familiar Keynesian tropes (eg, ‘Keynes wanted to save capitalism’) without rolling my eyes.

I really dislike fawning Keynesians because I used to be one when I was a TA for Hyman Minsky back in college (he was a Post-Keynesian). As such I was amored with Keynes, and read many biographies about him. There’s no greater ire than that of early infatuations, in part because we feel tricked, and these objects remind us of a naive earlier self that wasted part of our precious finite life on a wrong road. Anyway, I can’t can read the familiar Keynesian tropes (eg, ‘Keynes wanted to save capitalism’) without rolling my eyes.

A good indicator of a failed vision is a fanciful endgame. If that endgame is clearly wrong the vision is wrong. Marxists and their ilk thought the rate of profit would continually fall, until the proletariate took over and the state withered away. In the 1940’s economists thought that while capitalism offered greater liberty, the higher productivity of socialism would overtake capitalism. And then there’s Keynes’ famous 1930 essay The Economic Possibilities of our Grandchildren, in which he imagined that in 100 years or so, the greatest problem would be how to spend our leisure. Note that Frank Knight, Ludwig von Mises, and Freiderich Hayek never considered this possibility, highlighting their more accurate understanding of human nature.

Anyway, the latest Keynesian thumbsucker to take on this essay is biographer Robert Skidelski and son:

The irony, however, is that now that we have at last achieved abundance, the habits bred into us by capitalism have left us incapable of enjoying it properly. The Devil, it seems, has claimed his reward… The point to keep in mind is that we know, prior to anything scientists or statisticians can tell us, that the unending pursuit of wealth is madness. The first defect is moral. The banking crisis has shown yet again that the present system relies on motives of greed and acquisitiveness, which are morally repugnant.

This pompous blowhard grew up part of Britain’s upper class (he’s a Baron, whatever that means), and watching one’s status fall stings. Now he wishes money, and the market skill generally associated with it, weren’t so important for determining one’s social status anymore (though it was fine when gramps made the family fortune that bought his peerage).

He asserts that because Westerners got rich because we are intrinsically greedy, we now are rich but do not enjoy it because we are greedy: a Faustian bargain indeed! Yet, looking at hunter gatherers or hippies, both anti-materialists, I hardly see a more cultured, meaningful, or higher levels of existence. Mark Zuckerberg, meanwhile, seems centered, nice, intelligent, and interesting.

As per greed being repugnant, I don’t see what is intrinsically wrong with greed if such people are not hurting me. Minding my business under the rubric of safety or fairness, in contrast, is a much more common sort of intrusion in my life, and extremely unwelcome. Greedy people who pay for themselves by creating things of great value to others are both more fun and virtuous than do-gooders who spend all day thinking about new ways to force other people to work for other people. Of course, there’s a lot of luck and skulduggery involved in any market economy too, but it’s more fair than anything else I’ve seen.

Skidelski assumes that we should be egalitarians, and so, anyone wealthier than me hurts me via my now lower relative wealth, regardless of what he does with the wealth. That’s not society’s problem, that’s his problem.

He imagines the standard Marxian utopia of people engaged in thoughtful, productive, artistic activities, and notes we don’t seem geared that way right now:

The pleasures of urban populations have become mainly passive: seeing cinemas, watching football matches, listening to the radio, and so on. This results from the fact that their active energies are fully taken up with work; if they had more leisure, they would again enjoy pleasures in which they took an active part.

So, he advocates we all become artisans of some sort, making homebrew, tending gardens, writing poetry. Yet he notes people like to relax by just watching a movie. If they didn’t have a job, would they then more actively partake in their leisure? I doubt it. As Henry Ford said, I can think of nothing less pleasurable than a life devoted to pleasure.

People get most of their pleasure, and meaning, being useful to others, which includes inspiring the admiration or happiness of others by one’s actions. Every time I make my daughter squeal with delight makes me thankful to be alive, because I know she really loves me, and I work to provide her with things and habits that will make her prosper, and hope that at some point after I’m gone she will remember me with sincere gratitude. A healthy wage is a strong correlate with one’s usefulness to non-family members, especially if you work in field without a lot of regulation.

Our valuations are not just internal, which is why in Robert Nozick’s famous experience machine thought experiment where one is asked if they could spend their life in some sort of holodeck that offered incredible but fake experiences, most people don’t want the fantasy life. This is because living in a morphine high of solipsistic pleasure isn’t estimable, but rather, pathetic. A satisfying life affects other people in a positive way, which is why those ‘flow’ advocates really don’t understand what they are talking about–it’s not the flow, its the feeling that one’s focused actions are banking esteem in some communal credit bank, even if it is in some future world. It’s paradoxical that those focused on mandating altruism seem to think satisfaction can and should come purely from within.

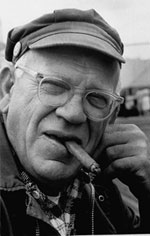

In contrast to the Keynesian vision of us all trying to figure out how to spend our endless vacation, there’s Eric Hoffer, the enigmatic philosopher who appeared out of nowhere around 1934 in California at age 34, and claimed to be an autodidact longshoreman. I suspect he was a German immigrant who at one point was a rabbinical student, and wanted to avoid immigration restrictions so he made up some story about growing up in Brooklyn.

Tom Bethell’s recent biography of Hoffer notes his vision of the future was prescient, not fanciful, highlighting a much greater profundity. Hoffer himself didn’t take much to make him happy: a well-written book to read, and evidence someone thought well of him. He thought intellectuals found free societies a threat because such societies didn’t need mandarins directing them, and if not flattered would help incite the masses to some sort of revolution. A man is likely to mind his own business when it is worth minding, and so those unhappy with their own meaningless affairs will focus on minding other people’s business. Hoffer noted one must not merely provide for those without meaning in their lives, but provide against them, because in a democracy and market economy their preferences will have power. Those who see their lives as inferior and wasted crave equality and fraternity more than they do freedom, and this can cause a Republic to fall to a democracy, and ultimately a tyranny.

Tom Bethell’s recent biography of Hoffer notes his vision of the future was prescient, not fanciful, highlighting a much greater profundity. Hoffer himself didn’t take much to make him happy: a well-written book to read, and evidence someone thought well of him. He thought intellectuals found free societies a threat because such societies didn’t need mandarins directing them, and if not flattered would help incite the masses to some sort of revolution. A man is likely to mind his own business when it is worth minding, and so those unhappy with their own meaningless affairs will focus on minding other people’s business. Hoffer noted one must not merely provide for those without meaning in their lives, but provide against them, because in a democracy and market economy their preferences will have power. Those who see their lives as inferior and wasted crave equality and fraternity more than they do freedom, and this can cause a Republic to fall to a democracy, and ultimately a tyranny.

In other words, Hoffer describes the essence of the Liberal desire to micromanage society into perfect equality at the expense of liberty. We haven’t figured out a good outlet for these do-gooders, or a good way for those without a purpose to find life rewarding, so they continue to plague us with their plans and angst. That’s a realistic vision of society, a future problem that is real yet potentially soluble.

Leave a Reply