The labor force participation rate ticked up in May, as did the rate of unemployment. As we have noted in the past, the near-term trajectory of the unemployment rate depends critically on what happens to the participation rate. So the question is, can we expect further upward changes in the participation rate? The answer depends a lot on the labor market attachment of those that are currently out of the labor force.

A few weeks ago, my frequent coauthor, Julie Hotchkiss, wrote about what we can gain from detailed labor market data about the activities of people who have exited the labor force. In her posting, she discussed the overall increase in exits from the labor force, with a focus on 25–54 year olds. Her work concluded that while people identified “Household Care” as the dominant activity for those not in the labor force, there has been a significant upward shift since the recession in those indicating “School” or “Other” as their primary reason for not being in the labor force. A supposition is that at least those that indicated they were in school would reenter the labor force at some point, doing so with a higher level of skills or, at least, with skills that are better aligned with labor demand. However, because we know little about those in the Other category, the future labor market attachment for them is less clear.

This post explores data on transitions into the labor force, primarily for those in the Other category. As in the earlier blog, the focus is on individuals aged 25–54, as retirement dominates the activity of older individuals not in the labor force and schooling dominates the activity of younger individuals not in the labor force.

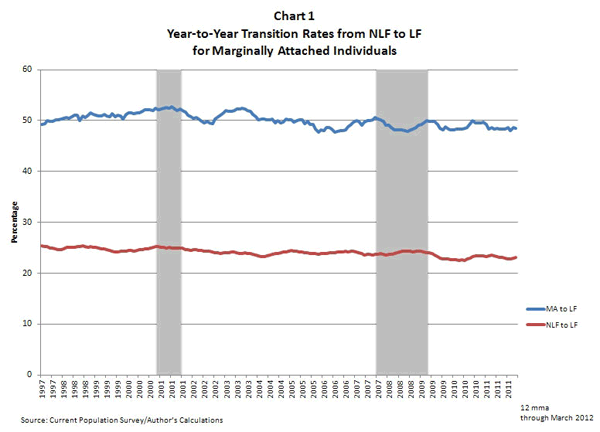

One indicator of whether those in the Other group are planning to reenter the labor force is whether the individuals in this group are classified as marginally attached to the labor force. A nonparticipant who is marginally attached indicates they want employment or are available for employment. Also, they indicate having looked for a job in the previous year but not actively looking for a job at present. Using monthly data from the Current Population Survey (CPS) that are matched year over year, we see that the marginally attached workers do transition back into the labor force at twice the rate of all individuals who are not in the labor force, as chart 1 illustrates. These rates are relatively stable over time.

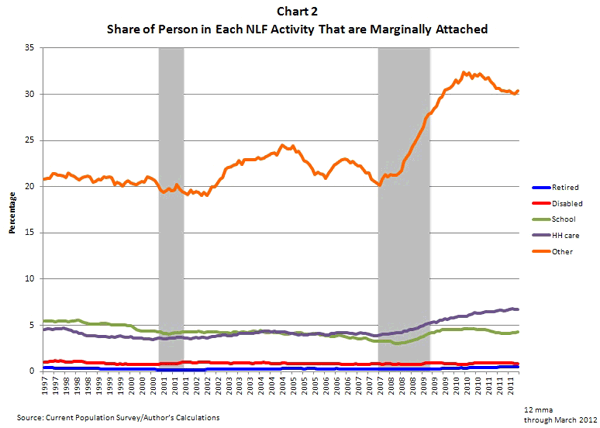

As chart 2 shows, a much higher proportion of individuals in the Other category are marginally attached to the labor force, compared to other types of nonparticipants. Moreover, the percentage of these marginally attached nonparticipants has increased from around 20 percent to 30 percent over the last three years.

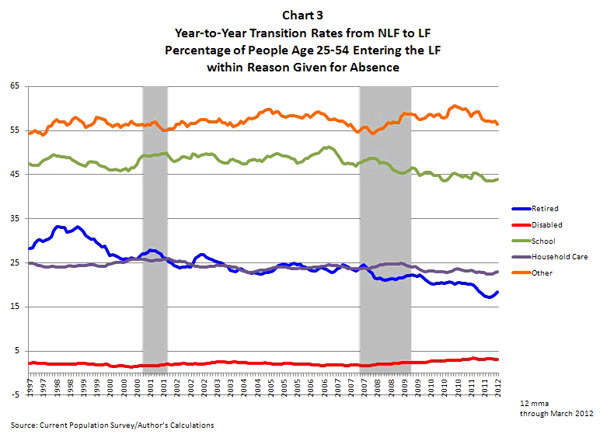

This higher probability of marginally attached workers returning to the labor force combined with the significantly increased share of marginally attached workers in the Other category suggests that we should expect to find a higher share of those in the Other group returning to the labor force than we’ve seen in the past. But it turns out that this expected development is not what has happened. The Other group also includes individuals who are not marginally attached to the labor market, and their transition rates into the labor market have declined. On net, while the transition rate to employment is highest for the Other category (reflecting the large of share of marginally attached), the transition rate into the labor force does not fully reflect the increased level of marginal attachment to the labor force.

The group with the next highest transition rate to employment is in the School category, which reflects the inherent transitory nature of that activity. However, it is noteworthy that the school transition rate is lower than it was before the recession. This development reflects an increase in the share of individuals continuing to indicate that school is their primary reason for not participating in the labor force from one year to the next. And it suggests that the lower opportunity cost of attending school is influencing the decision to remain in school longer.

While these trends suggest that we could expect to see higher rates of return to the labor force going forward, this potential development will likely require a much better showing of jobs numbers than were seen today before kicking in.

Leave a Reply