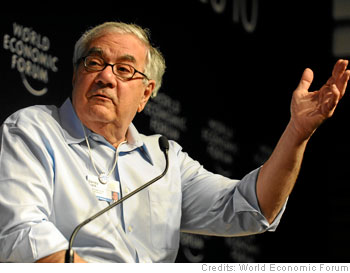

Rep. Barney Frank did incalculable damage during his tenure as one of the most influential legislators overseeing the American financial services industry.

Rep. Barney Frank did incalculable damage during his tenure as one of the most influential legislators overseeing the American financial services industry.

From his support of the Community Reinvestment Act, which was no more than a tool for local pressure groups to extract money from banks, to his denial of the risks that Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac posed to the Treasury as they consumed the mortgage financing market, Frank saw his role as that of a strategically placed siphon whose function was to direct other people’s funds to those he deemed more deserving.

The Massachusetts Democrat announced Monday that he will not seek reelection next year. He cited his age and the length of his tenure in office, saying, “By the end of next year, I will have been doing this for 45 years with one six-month sabbatical.” That tenure will have included 32 years in the House of Representatives. At 71, no one can blame Frank for looking to retirement.

My guess is that Frank is more concerned about his diminished congressional role, since the Republican takeover of the House cost him the chairmanship of the Financial Services Committee this year, than about his age or general weariness. Being a congressman is not nearly as much fun these days, especially now that the fruits of his labors are so appallingly evident.

While Frank and his cohorts like to blame “Wall Street” for the world’s financial ills, the problems in this country’s banking sector grew out of housing market, where Frank made his biggest mark. Even after it was clear that his stance on Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac was, to put it charitably, misguided, Frank insisted that he was not to blame for their eventual collapse. “The mistake I made was a nonoperational one — I wasn’t in power. From the day I became chairman, I think we did everything we could,” The Boston Globe reported Frank said.

It is only fair to note that Frank is correct that Republicans, as well as he and his fellow Democrats, played their part in facilitating the federalization of the mortgage industry. But the Republicans, who should have had more sense, were just in it for the campaign dough; Frank and his fellow Democrats were the true believers that government had a role to play in making home ownership available to people who could not afford it and who would have been better off without it.

That’s not to say Frank isn’t smart, or hard-working, or courageous. He is all those things. It took serious guts to be the first congressman to voluntarily acknowledge being gay in 1987, when Frank came out publicly. It took fortitude to acknowledge his relationship with a male prostitute and to accept a reprimand for fixing a myriad of parking tickets for the same.

When push came to shove in 2008, Frank gave vital behind-the-scenes support to then-Treasury Secretary Hank Paulson, to do whatever needed to be done to keep the banking system from collapsing. Though he and Paulson were very different, the two men developed a deep trust. In the forward to Paulson’s book On the Brink, Frank wrote that they “admired each other’s integrity and commitment to the public good, and shared a similar and natural understanding of the crisis that faced [them].” Their cooperation kept the crisis from becoming worse than it was.

But in a bizarre triumph of ideology over experience, Frank included provisions in the Dodd-Frank financial overhaul legislation that would limit the flexibility of the Treasury and the Federal Reserve in a similar crisis in the future.

In the end, Frank’s career was always about maximizing power: particularly Congressional power, and most particularly his own. I wish him a very happy, if sadly overdue, retirement.

Threading close to committing “The Big Lie” there, you are.