It now looks like the next installment ($8 billion Euros) of the rescue package for Greece will not be disbursed until mid-November. Greece is likely to run out of cash before that. The austerity measures that Greece has imposed are pushing the country deeper into recession.

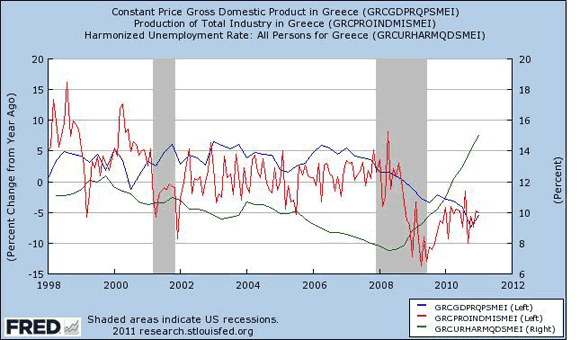

Greece’s real GDP is likely to be down 5.5% and will continue to drop in 2012. This has caused tax collections (never very robust in Greece to begin with) to plunge, and its budget deficit is not getting any better.

The budget deficit is now expected to be 8.5% of GDP this year, up from a projection a few months ago that it would be 7.6% of GDP. The Greek government now projects that next year it will be 6.8%, above the 6.5% target that was part of the bailout agreement. The Greek government cannot borrow more in the open market. Most Mafia loan sharks charge less than the market is charging for the Greek government to borrow for one year.

This has led to the need for more austerity measures. For example, the country will reduce its private sector workforce by 30,000 by December. The entire population of Greece is just 11.3 million, so 30,000 additional jobs lost in the public sector alone is a significant number, roughly the equivalent of over 800,000 jobs here in the U.S.

Here is the basic economic picture of Greece since 1998, just before the Euro replaced the Drachma. Unfortunately the data only goes through the first quarter, but things have not gotten any better since.

The Greek economy is deeply uncompetitive, and as a result it has been running massive trade deficits since it adopted the Euro. In the process, it has gone deeply into debt to the rest of the world, particularly to the other countries in Europe.

The normal result of deep and persistent trade deficits — particularly in a small open economy — would be for the currency to depreciate, and thus make imports more expensive and exports more competitive. However, since Greece does not have its own currency, that adjustment mechanism by definition cannot work. So how could Greece get out of this mess?

- The debt could be forgiven, through a debt exchange program that imposed very steep haircuts on the holders of the debt, and much steeper than have been negotiated so far. That, however, would threaten the solvency of many big European banks (the big U.S. banks like JPMorgan (JPM) and Wells Fargo (WFC) have minimal direct exposure to Greece; however, they do have substantial exposure to those European banks).

- The Euro could weaken substantially. That would make Europe, and by extension Greece, more competitive versus the rest of the world. However, Greece is only a tiny part of the overall Euro-area GDP, and such a weak Euro would not be in the interest of the core of Europe. Germany and the Netherlands are certainly competitive enough at the current level of the Euro. The key trade-off in weakening your currency is that it tends to lead to higher levels of inflation. Also, since foreign exchange markets are always relative value markets, a weak Euro means a strong U.S. dollar. Greece is not the only country in the world that runs chronic massive trade deficits — the U.S. runs one that is equal to all the other trade deficits in the world. And a strong dollar is the last thing the U.S. economy needs right now.

- Somehow productivity in Greece could surge, while Greek workers got no benefit from the increase in productivity. That would cause unit labor costs to drop and make the country more competitive. The chances of that happening anytime soon on the scale needed are so low as to approach a mathematical impossibility.

- Greece could continue to pursue a policy of internal devaluation. This is what the core of Europe has been demanding: austerity and more austerity. The idea is that it would push Greek unemployment up to the point where Greeks would be so desperate for work that they would take extremely low wages. Think third-world wages, not low U.S. wages here. That is a very long, slow, and extremely painful process. In the short-to-medium term, it simply depresses the Greek economy more, and that makes it even harder for them to service their debts.

The final option would be for Greece to leave the Euro and go back to the Drachma. That would be a messy divorce. Bank deposits in Greece would be converted to Drachma from Euros, but the value of the Drachma would be far less than the Euro. As people saw that coming, they would all rush to take their money out of Greek banks and put it in banks that would remain on the Euro.

While there is no exact precedent for a country doing this, the best analogy would be what happened to Argentina when it abandoned its currency board, which had effectively pegged to Argentinean Peso to the U.S. Dollar. This would cause very big losses among the European banks, on par with the haircuts discussed above. The key difference would be that Greece would be effectively imposing them, rather than simply trying to get the banks to voluntarily write off billions of Euros.

The core governments of Europe would probably have to step in with something that looks very much like the U.S. TARP program to recapitalize the banks. The German government would have to prop up Deutsche Bank (DB), the French would have to prop up Societe General and the program size would probably total as much or more than the U.S. had to deal with in 2008 and 2009.

However, with a super-cheap Drachma, Greece would instantly become more competitive. A hotel room on Crete that currently costs 50 Euros a night now would cost, say, 25 Euros. Germans and French take a lot of vacations, and they would be much more likely to take them in the Greek Isles.

It would not be a painless path for Greece by any means. The cost of anything they imported — very significantly including oil — would soar. While lots of others would come to Greece to vacation, no Greek could dream of vacationing abroad. Still, after a rough year or so following the abandonment of the dollar peg by Argentina, the Argentine economy has recovered nicely, as shown in the graph below (from this source).

However, if Greece goes down this path, others are likely to follow. Greece leaving would probably result in the whole Euro experiment falling apart. The Euro has had some very major advantages (imagine if you had to exchange your currency every time you went from New Jersey to New York). The benefits were not only economic, but political as well, and have helped to soothe animosities that go back hundreds of years.

However, to succeed, the monetary union had to be followed by a fiscal union. A fiscal union means a political union, as fiscal policy is about taxing and spending. That was simply a bridge too far for the Europeans. I think it remains so. The dissolution of the Euro looks like the best path out of a very bad situation to me.

Leave a Reply