The 2012 Greek debt restructuring was the largest one in the history of sovereign defaults. This column discusses the lessons from this historically unprecedented episode. Delaying the restructuring implied that externally held debt remained higher than it would have been otherwise. Supportive crisis management is necessary for smooth restructuring to take place in a currency union.

Background

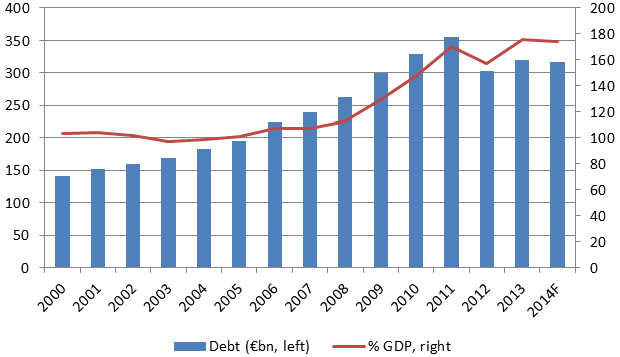

The 2012 Greek debt exchange and subsequent buyback was a key episode in the Eurozone debt crisis (Wyplosz 2010, 2013). It was the largest debt restructuring in the history of sovereign defaults, and the first within the Eurozone. Though it achieved historically unprecedented debt relief – amounting to 66% of GDP – it was ‘too little too late’ in terms of restoring Greece’s debt sustainability (Figure 1). Its historical significance lies not only in its unprecedented size, but also in its timing, size of creditor losses, modalities, and potential for contagion to the rest of the Eurozone periphery.

In a recent paper (Xafa 2014), I examine the Greek debt exchange and the subsequent buyback against the background of the Eurozone crisis, with a view to drawing lessons for any future debt restructuring in the Eurozone and beyond. I find that delaying the restructuring implied that externally held debt remained higher than it would have been otherwise, adding to the transfer of real resources that will be required to service it. Overall, the Greek experience shows that an orderly restructuring is possible in a currency union, but that firewalls and supportive crisis management institutions are necessary for it to take place smoothly, without major contagion effects. The substantial increase in the ESM’s ‘firepower’ and the theoretically infinite backstop provided by the ECB’s Outright Monetary Transactions make it possible to address any future sovereign episode earlier on, while limiting the scope for contagion. With the crisis management institutions and procedures now in place, as well as much stricter fiscal surveillance and ‘bail-in’ of bank creditors, the Greek experience is likely to remain unique in the history of debt restructurings, although some lessons can be learned from its specific features. The current article narrowly focuses on these lessons.

Figure 1. Greece: General government debt

Source: IMF Fiscal Monitor, April 2014.

The 2012 Greek debt restructuring

Greece was the first Eurozone country to request official financial assistance in May 2010, with Ireland following in November 2010, and Portugal in May 2011. The crisis was triggered by the revelation of the newly elected Papandreou government in October 2009 that the budget deficit would amount to 12.5% of GDP – twice as high as previously reported (it was later confirmed at 15.6%). The large discrepancy in the reported figures undermined the credibility of EU budgetary surveillance and led to a sharp increase in Greece’s borrowing costs, with the slide accelerating after successive credit downgrades. Market sentiment plunged in the spring of 2011, fuelled by social unrest, a deepening recession, and expectations of a debt restructuring. Sharply lower confidence triggered deposit outflows, as fears grew that Greece would be forced to exit the Eurozone if the ECB stopped providing massive liquidity support to preserve stability. Although the possibility of a sovereign default already loomed, a debt exchange was only concluded in March 2012.

The Greek case is quite unique in the sovereign debt literature. In contrast to emerging market debt, which is typically issued in foreign currency under foreign law, the bulk of Greece’s debt was issued in domestic currency under domestic law. By virtue of its Eurozone membership, which prohibits monetary financing of deficits, Greece was bankrupt in its own currency but unable to inflate its debts away. On the positive side, the terms of domestic-law bonds could be amended unilaterally through an act of Parliament. However, Greece used legislative action only to retrofit collective action clauses in bond contracts in order to facilitate the restructuring. A coercive restructuring involving a unilateral change in payment terms by the debtor was thus avoided, and so was disorderly default, defined as a unilateral decision by the borrower to suspend debt service payments due to inability or unwillingness to pay. Instead, Greece negotiated a pre-emptive debt exchange with creditors as part of a second rescue package agreed with the IMF and the EU. Greece’s unique circumstances make its debt restructuring an unprecedented event of limited relevance to emerging markets.1 However, it contains some important lessons for any future debt restructurings within the Eurozone.

Proposals to facilitate debt restructurings

The delay in Greece’s restructuring and its generous treatment of holdouts has triggered proposals for an intermediate approach between two extremes: a statutory approach, such as the Sovereign Debt Restructuring Mechanism proposed by the IMF in the aftermath of Argentina’s 2001 default but rejected by creditors (Krueger 2002), versus the prevailing contractual, market-based approach based on collective action clauses (CACs) agreed to on a case-by-case basis.2, 3 As there is little appetite for reviving the debt restructuring or other arbitration measures, current proposals focus on enhancements of the prevailing collective action clauses to secure creditor participation and expedite negotiations. To limit the risk that IMF resources are only used to bail out private creditors, it has has proposed a creditor bail-in as a condition for Fund lending in cases where the debtor has lost market access, until a clear determination if a haircut is needed can be made (IMF 2013a). Proposals also include the creation of a Sovereign Debt Forum to provide a venue for continuous improvement in the process of dealing with sovereign debt service issues and for proactive discussions between debtors and creditors to reach early understandings in order to avoid a full-blown sovereign crisis (Gitlin and House 2014).

Private creditors, on the other hand, represented by the Institute for International Finance (IIF), believe that good-faith negotiations remain the most effective framework for reaching voluntary debt-restructuring agreements, including in the complex case of debtors that are members of currency unions. They believe that the unilateral imposition of a stand-still by the debtor, condoned by the IMF, would “severely undermine creditor property rights and market confidence and thus raise secondary bond market premiums for the debtor involved and other debtors in similar circumstances” (IIF 2014).

Nevertheless, the IIF recognises that further enhancements to the contractual approach are desirable, including through more robust aggregation clauses.

Aggregation clauses and the holdout problem

While retrofitting collective action clauses ensured that the entire stock of Greek-law bonds (€177 billion) was exchanged, some holders of foreign-law bonds decided to hold out for full payment (€6 billion out of €28 billion of foreign-law bonds). These holdout creditors are being repaid in full to avoid a messy, Argentine-style litigation. The risk that creditors might seize Greek assets abroad was not considered worth taking to avoid payment on holdout claims representing just 3% of total eligible debt. In a parallel development, the case of NML Capital vs. Argentina that is being litigated in US courts has demonstrated that holdout creditors can have considerable leverage to frustrate a debt-restructuring agreement after it has been concluded.4 These two cases – though different – have focused attention on the need to minimise the potential for holdout creditors to block or frustrate a comprehensive sovereign debt restructuring.

The fact that holdouts were paid in full in Greece drove a wedge between local-law and foreign-law bonds in other heavily indebted Eurozone countries. Gulati and Zettelmeyer (2012) have proposed a voluntary exchange of local-law for foreign-law bonds in heavily indebted Eurozone countries, offering greater contractual protection to bondholders in exchange for a reduction in the debt burden. All new bonds issued by Eurozone countries after January 1, 2013 must include collective action clauses.5 However, the euro-collective action clauses remain vulnerable to the holdout problem by putting too much emphasis on supermajorities in individual bond series instead of permitting activation when an aggregate threshold is met across all bondholders (Bradley and Gulati 2012). Moreover, the bulk of outstanding debt in most Eurozone countries remains under local law without collective action clauses. To discourage litigation by holdout creditors, Buchheit et al. (2013) have proposed amending the ESM Treaty to provide immunity to a debtor country’s assets from attachment by holdouts.

Initiatives underway in a number of fora, including the IMF, the IIF, the US Treasury and the International Capital Markets Association, aim to set a better market standard for CACs. Drawing from the Greek case, the IMF has proposed exploring “the feasibility of replacing the standard two-tier voting thresholds in the existing aggregation clauses with one voting threshold, so that blocking minorities in single bond series cannot derail an otherwise successful restructuring” (IMF 2013). However, this approach does not differentiate across bondholders depending on the maturity of their claims. Subjecting all bonds to a uniform haircut, irrespective of maturity, implies a higher NPV loss on short-dated bonds. These issues illustrate the need for any new market standard to achieve a balanced treatment of debtor and creditor rights by including aggregation clauses and lowering voting thresholds on one hand, while maintaining a series-by-series majority approval voting safeguard on the other.

References

•Bradley, M and M Gulati (2012), “Collective Action Clauses for the Eurozone: An Empirical Analysis”, SSRN Working Paper, March.

•Buchheit, L C, M Gulati and I Tirado (2013), “The Problem of Holdout Creditors in Eurozone Sovereign Debt Restructurings”, January.

•Gitlin, R and B House (2014), “A Blueprint for a Sovereign Debt Forum”, CIGI Paper No. 27. March.

•Gulati, M and J Zettelmeyer (2012), “Making a Voluntary Greek Debt Exchange Work”, CEPS Discussion Paper 8754, January.

•IIF (2012), “Report of the Joint Committee on Strengthening the Framework for Sovereign Debt Crisis Prevention and Resolution.” October.

•IIF (2014), “IIF Special Committee on Financial Crisis Prevention and Resolution: Views on the Way Forward for Strengthening the Framework for Debt Restructuring.” January.

•IMF (2013), “Sovereign Debt Restructuring — Recent Developments and Implications for the Fund’s Legal and Policy Framework”, 26 April.

•Krueger, A (2002), “Sovereign Debt Restructuring and Dispute Resolution”, Speech given at the Bretton Woods Committee Annual Meeting, Washington, DC, June 6.

•Schadler, S (2013), “Unsustainable Debt and the Political Economy of Lending: Constraining the IMF’s Role in Sovereign Debt Crises”, CIGI Paper No. 19. November.

•Wyplosz, C (2010), “And now? A dark scenario”, VoxEU.org, 3 May

•Wyplosz, C (2013), “Messing up the next Greek debt relief could endanger the Eurozone”, VoxEU.org, 23 September

•Xafa, M (2014), “Sovereign Debt Crisis Management: Lessons from the 2012 Greek Debt Restructuring”, CIGI Paper No. 33, June.

•Zettelmeyer, J, C Trebesch and M Gulati (2013), “The Greek Debt Restructuring: An Autopsy”, Peterson Institute for International Economics, Working Paper 13. August 8.

Footnotes

1 To my knowledge, only Jamaica has restructured foreign-currency debt issued under domestic law. Russia and Uruguay restructured locally issued debt in 1998 and 2003 respectively, but this was denominated in local currency.

2 The contractual approach is described in the Principles for Stable Capital Flows and Fair Debt Restructuring, the voluntary code of conduct agreed between sovereign debtors and private creditors, which was endorsed by the G20 in November 2004. The IIF has adopted an Addendum to its Principles that takes into account the experience of the Greek debt restructuring (IIF 2012).

3 Collective action clauses (CACs) help overcome creditor coordination problems by allowing important terms of the bonds to be amended by a defined majority of holders. They facilitate a debt restructuring by making the amendments binding on all holders, including the dissenting minority. Essentially, CACs eliminate contract rights through majority voting without any court supervision and outside a rules-based statute.

4 The case concerns holdout creditors who are demanding full payment on their Argentine bonds issued under New York law by threatening to seize debt service payments to bondholders who participated in the 2005 Argentine debt exchange.

5 Article 12 of the ESM Treaty provides for the mandatory inclusion of standardized and identical CACs in all new Eurozone sovereign bonds, irrespective of their governing law. The motivation is clear: By facilitating debt restructurings, CACs can shift some of the costs of sovereign distress on to private creditors. In fact, the preamble to the ESM Treaty explicitly calls for “an adequate and proportionate form of private sector involvement […] in cases where stability support is provided accompanied by conditionality in the form of a macro-economic adjustment program.”

Leave a Reply