Back in April 2010 when it first seemed the Eurozone was about to crack up, I did a post on the lessons of the Eurozone crisis. I argued then that the main lessons were, one, countries joining a currency union should take seriously the optimal area criteria and the real exchange rate and, two, central banks should take seriously the task of stabilizing the growth of nominal spending. I still think these points are valid, but I now see a more important lesson from this ongoing crisis: avoid relationships where one party to the relationship is domineering and has a history of abuse. In short, avoid bad relationships.

In the case of the Eurozone relationship the dominant party is Germany. Its desires have largely shaped the direction of the Eurozone and continue to do so today, even though it only has historically made up at most about 30% of the Eurozone economy. This uneven relationship has been very apparent lately as the future of the Eurozone seems to hang on the day-to-day developments in Germany. For example, the fate of the currency union inched closer to collapse a few weeks ago when German’s constitutional court ruled against a supranational fiscal authority and when a German vote of no confidence was effectively issued for the ECB by the resignation of the German representative Jurgen Stark from the ECB’s board. Then, last week the mood improved when German Chancellor Angela Merkel said the Eurozone must stick together. Now new polls show Merkel loosing influence and the Eurozone’s breakup looks more likely. That these German developments can so easily drive the ups and downs of the Eurozone outlook speaks to dominance of Germany in the Eurozone relationship.

Another way to see the inordinate influence of Germany is to look at the inflation-hawk culture of the ECB inherited from the Germans and its influence on the evolution of ECB monetary policy. Many studies, such as this 2010 report from Barclays Capital or this one from the WSJ, have shown using Taylor Rule estimates that while ECB monetary policy has been stabilizing for Germany over the past decade it has been destabilizing for the periphery. In particular, monetary policy was too loose for the periphery when the Eurozone was first formed and more recently have become too tight for them.

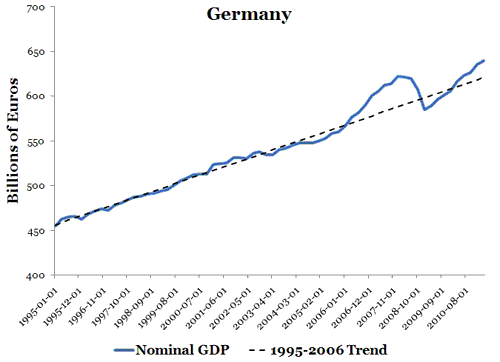

This tendency to change ECB monetary in a manner that best serves Germany can be vividly seen by looking at the history of nominal spending for Germany and for the rest of the Eurozone. The first figure below shows the case of Germany along with a trend. It shows that not only has Germany’s nominal spending returned to trend, but that it is has slightly exceeded it in recent quarters. This explains why the ECB raised interest rates earlier this year and has failed to cut them despite the severity of the crisis. The German economy needed some tightening and the ECB delivered it.

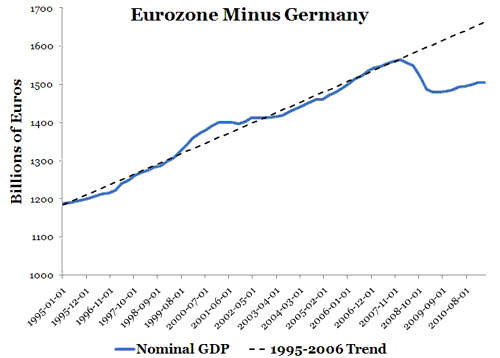

The next figure shows nominal spending for the rest of the Eurozone. The difference between the two figures is shocking. Not only is nominal spending below trend, but the difference continues to increase. The ECB is failing miserably here to stabilize nominal spending for the other 70% of the currency union. This should remove any doubt about the inordinate influence of Germany on the Eurozone.

Finally, it is worth nothing that the Eurozone crisis is not the first time Germany’s internal policy goals were promoted at the expense of partner countries. The European Monetary System (EMS), which tied other European currencies to the German Deutsche Mark, erupted into a crisis in 1992 when the German central bank adopted a tighter monetary policy that was appropriate for Germany but too tight for the other countries in the exchange rate system. Thus, there is an tendency for Germany to use its inordinate influence over European monetary affairs in a manner not conducive to the overall monetary system. This suggests to me that maybe the best solution to the Eurozone crisis is not to fix currency union but for Germany and like-minded countries to leave it. Ambrose Evans-Pritchard, Ramesh Ponnuru, and others have made the case for something like a two-tiered EMU where Germany and other austerity-embracing countries adopt a harder currency while letting France lead the Euro block. Here is Evans-Pritchard’s idea:

My solution – like that of Hans-Olaf Henkel, the ex-head of Germany’s industry federation (BDI) – is to split EMU into two blocs, with France leading a Latin Union that keeps the euro. This bloc would devalue but not by 60pc, yet uphold its euro debts intact. The risk of default and banking crises would decrease, not increase.

The German bloc could launch their Thaler, recapitalizing banks to cover losses from rump euro debt. Disruptions could be contained by capital controls at first. None of this is beyond the wit of man. My bet is that aggregate losses would be lower than the status quo, and the long term outcome much healthier. The EU might even carry on, unruffled.

I haven’t always held this view, but am becoming increasingly sympathetic to it. Sometimes it is for the best of all that a bad, abusive relationship gets terminated. Maybe it is time for Germany to leave the Eurozone.

Leave a Reply