We finally get our debt-ceiling deal, only to watch the S&P500 fall 3.7% from Thursday’s close. What gives?

Let me begin by suggesting that the debt debate lumped together three issues that I regard as separate problems. There was first the immediate challenge of how the U.S. government was going to pay its bills for the rest of August. Second is the near-term need to bring unemployment down– we need to see more robust economic growth in order to get Americans back to work as quickly as possible. And third is the daunting challenge of putting U.S. fiscal policy on a sustainable long-run course– debt cannot continue to grow as a multiple of GDP, and something needed to change to ensure that it did not.

The first problem– finding a way to meet the government’s immediate spending commitments– was entirely a monster of Congress’s own creation. Congress had stipulated a certain level of spending. Congress had further approved of taxes that resulted in revenue substantially below those spending levels. It would then seem obvious that the government needed to borrow additional funds to make up the difference. Yet Congress had ruled that out as well in the form of a standing limit on how much could be borrowed. It was unclear how this was all supposed to be reconciled, and how exactly items such as Social Security payments, soldier salaries, and sums owed creditors were all going to be paid this week. The clean answer would of course have been to raise the debt ceiling as a stand-alone act, and separately modify the spending or tax policies if legislators didn’t want to keep on seeing the total sum borrowed continue to rise.

So perhaps we should be thankful that at least one thing we got out of the last-minute deal was a lifting of the debt ceiling, allowing August federal payments to be made on schedule. But I think there was some damage done by carrying the drama as far as we did. People were getting nervous about how this would all play out. When people get nervous they sit on the sidelines, and when folks sit on the sidelines, the economy can stall. Concerns about how this would all end up could have been one factor contributing to the July plunge in consumer sentiment, and that loss in confidence could also be relevant for recent weakness in consumer spending. I found myself getting calls from friends worried about what the wrangling in Washington might mean– was it still safe to be holding T-bills, and if not, where should people put their money? A few years ago, hardly anybody was talking seriously about the possibility that the U.S. might fail to honor its statutory debt. Today, there is open discussion of downgrading U.S. debt. Although we got through this episode, a residual uneasiness is still going to be there, and may leave us with less room to maneuver when a real problem shakes people’s confidence.

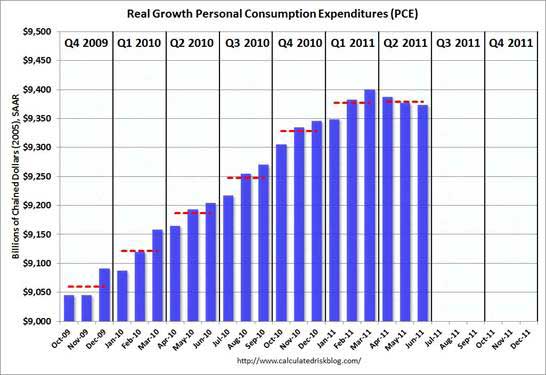

Source: Calculated Risk

The second problem– getting the unemployed back to work– is one that could only be aggravated by recently debated measures. I share the strong concern held by many about the need for long-run fiscal sustainability. But I feel equally passionately that cutting near-term spending is counterproductive. Reducing government spending is taking away somebody’s income, namely, that of the government employee, contractor, or recipient of transfer payments. Granted, we will soon need to start making exactly those cuts. But the time to do so is when there are private sector jobs available to pick up the slack. If we try slashing the 2012 budget, it will just add more people to the current swollen unemployment rolls. Again, perhaps another thing to be thankful for in the budget deal is that the spending cuts it implements for 2012 appear to be pretty minor.

And how about the long-run objective– putting fiscal policy on a responsible course for the next decade? The legislation sets a target of cutting the cumulative deficit by $1.5 trillion over the next decade, with a complicated series of contingencies and triggers that are supposed to ensure this happens. What bothers me about this is that there has been no real discussion or agreement as to exactly what we’re going to do or how we’re supposed to do it. And the reason for that absence of real discussion is pretty simple. The voters want to believe they can get something for nothing, and the politicians are only too willing to promise exactly that.

Dealing responsibly with the long-run challenge in a way that does not destabilize the economy in the short run strikes me as a fairly straightforward problem. Measures such as raising the eligibility age for Medicare and Social Security and increasing the co-pay for Medicare on a defined schedule over time achieve exactly those objectives. Perhaps I will be pleasantly surprised and all this will eventually emerge from the sequence of procedures that today’s legislation puts in play.

I know, nobody else was all that happy with the deal either, and you could argue that the deal does at least muddle through, in its own way, with all three objectives I articulated above. So if the deal is almost sort of reasonable, how come the stock market tanked on the news?

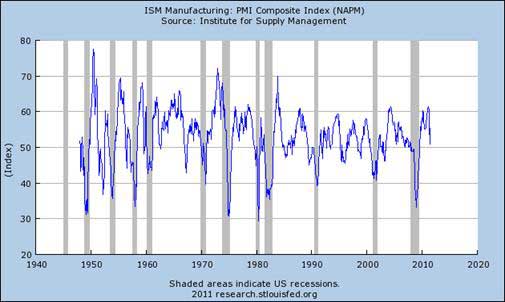

Source: FRED

One answer is that there has been other unfavorable news arriving at the same time. At the top of the list I would put yesterday’s manufacturing ISM report. This is a diffusion index, for which a value above 50 indicates that more facilities are reporting improvements than are reporting declines. The July value for the index (50.9) means that manufacturing is still expanding. The problem is, if the economy were actually growing, we expect to see a number above 50– the historical average value for this index is 52.8. And during the last year, this measure had been averaging 57.7. Manufacturing had been the one bright spot in the economy. Had been– past tense.

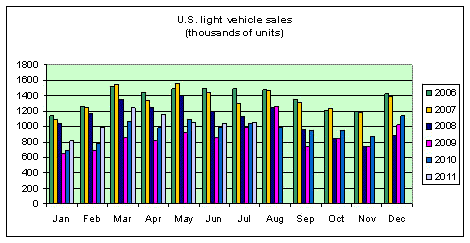

Data source: Wardsauto.com

And today we received so-so auto sales numbers for July. The seasonally unadjusted number of light vehicles sold was up ever so slightly from that for June 2011 or July 2010, but in each case the increase is less than 1%. The one potentially encouraging detail is that sales of domestically manufactured vehicles were showing decent gains, with low numbers for Japanese imports holding down the totals. The Wall Street Journal offered this analysis:

Japanese auto makers have been hurt by dwindling dealer inventories, a lingering effect of the March 11 earthquake that disrupted auto and parts production in Japan and North America….

Despite the slowdown, executives expressed confidence that industry sales will improve. They said more Toyota and Honda vehicles will arrive on dealer lots in the fall, allowing those companies to discount prices more heavily.

So things may improve. But it certainly appears that the first half was pretty dreadful for the overall economy, and the promised rebound didn’t begin in July.

Which is enough to deflate whatever enthusiasm you might have felt at the news that the federal government has figured out a way to honor its scheduled payments for the next few months.

Leave a Reply