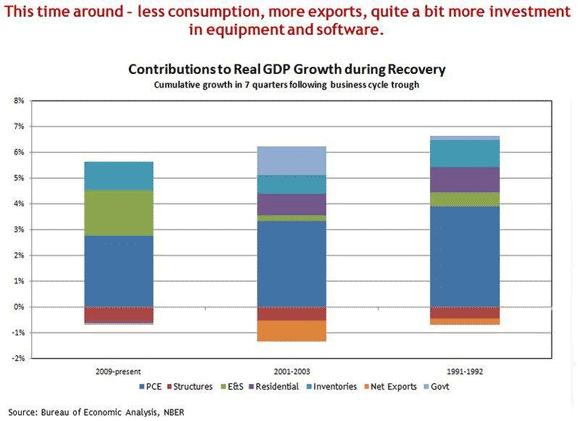

Given that thoughts of high structural unemployment continue to emerge in Fed thinking, the topic bears ongoing scrutiny. Especially so for me personally, as I have long seen the need for structural shifts that address the US current account deficit – but should such adjustments require persistently high unemployment rates? Some affirmation of my general story comes via David Altig, who recently posted this chart:

Note the shift in relative growth patterns – less consumption, more investment, and net exports at least a less negative drag. This seems consistent with a shift away from the externally supported pattern of household consumption so evident in the past decade. And in discussing the general disappointment with the strength of the recovery, Altig says:

The undeniable (and relevant) human toll aside, the current recovery seems so disappointing because we expect the pace of the recovery to bear some relationship to the depth of the downturn. That expectation, in turn, comes from a view of the world in which potential output proceeds in a more or less linear fashion, up and to the right. But what if that view is wrong and our potential is a sequence of more or less permanent “jumps” up and down, some of which are small and some of which are big?

The implication is that perhaps we are closer to potential output than is widely believed. Now, before you roll your eyes, as I am inclined to do, note the CBO estimate of potential output is not the only estimate. Menzie Chinn reminds us of the variety of estimates of potential output, some of which suggest that, at the moment, the output gap is actually positive.

Why might we believe that potential output has suffered some sizable, negative downward shock? Altig did not provide an explanation, but one can find the same idea in the most recent FOMC minutes:

Others, however, saw the recent configuration of slower growth and higher inflation as suggesting that there might be less slack in labor and product markets than had been thought. Several participants observed that the necessity of reallocating labor across sectors as the recovery proceeds, as well as the loss of skills caused by high levels of long-term unemployment and permanent separations, may have temporarily reduced the economy’s level of potential output (italics added). In that case, the withdrawal of monetary accommodation may need to begin sooner than currently anticipated in financial markets.

“Several” means a nontrivial contingent. Notice the two, distinct explanations. One is a structural change story – the economy needs more IT workers, and less retail staff, but the latter cannot easily become the former. I cannot entirely dismiss this concern, as it is consistent with my own thoughts of how the US economy should evolve.

The second point is also not easily dismissible, at least in its entirety. Left leaning economists have worried that a protracted period of high cyclical unemployment could induce an increase in structural unemployment – that those workers out of the labor market for two years become essentially unemployable at anything remotely like their previous wages. Maybe not even two years of unemployment, perhaps just a day. See Ryan Avent here.

The standard argument against the structural change story is to turn to the data itself and recognize that job losses have been widespread throughout the economy. Thus, while some structural change is happening in the background, the primary issue at hand is really a demand shortfall. See Brad DeLong here. Moreover, one should expect increasing wage differentials. But Federal Reserve staffers have had trouble identifying such effects. From a good overview on Bloomberg:

Mary Daly holds up two charts containing 33 bars that all point down. They show eight industries getting hit equally hard after the 18-month recession ended in June 2009, suggesting that much of the past two years’ high unemployment is broad-based and should dissipate as the economy improves.

Daly is among researchers throughout the Federal Reserve system — from San Francisco to Philadelphia and the board in Washington — who are scouring data, examining models and gleaning anecdotes to determine why the jobless rate has remained stuck around 9 percent or more since April 2009. Most are reaching the conclusion that any long-term, structural shifts in the labor market aren’t significant enough to keep the U.S. from returning to a pre-crisis unemployment level of 5 percent to 6 percent by about 2016.

“If we were mis-measuring the natural rate of unemployment, I would expect to see rapid wage growth in some sectors offset by wage declines in others,” said Daly, 48, who heads the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco’s applied microeconomic research department. “I don’t see that. I see pretty uniform patterns across all sectors.”

I don’t quite see why if the structural shifts are not significant that is should take until 2016 to get unemployment back down to a normal range, but we will put that aside for the moment. The main point to the story, however, is that it is challenging to find the impacts of very large structural change in employment or wage data. Not that there are no effects:

The availability of extended unemployment benefits may have increased joblessness by as much as 0.8 percentage point and should have only a transitory effect as they expire and economic conditions improve, according to a January paper by Daly and San Francisco Fed researchers Bart Hobijn and Robert Valletta. Daly puts the natural rate at 6.25 percent and predicts it will fall to as low as 5.5 percent in five or more years.

Let’s give the benefit of the doubt to the structural change side of the story, and say the natural rate is at 7 percent. That still leaves over 2 percentage points of unemployment, and, currently, that number is moving in the wrong direction. Hence this is why overall wage growth remains weak (another factor suggesting fears that we are close to potential output are overblown).

Also arguing for a largely demand side explanation to the current weak employment numbers is what looks like a pretty obvious link between asset bubbles and full employment over the last decade. As long as households had a mechanism to support demand, achieving full employment was not a problem. If not households, then why can’t another form of demand fill the gap?

If I were to look for a sign that potential output has been breached, I would turn my attention to the trade deficit, which very much suggests domestic absorption exceeds domestic capacity. The challenge, however, is that a significant trade deficit still exists along with high unemployment. I would be happier if the trade deficit only coincided with low unemployment, which would suggest strains in satisfying domestic absorption with internal resources. In my opinion, this curious state of affairs is the consequence of allowing foreign central banks to manipulate the value of the Dollar to obtain a trade advantage, which in turn has created significant imbalances in global patterns of production and consumption (I wouldn’t fool myself with the belief this has anything to do with seeking greater investment returns). This, though, brings us back full circle – we should expect patterns of activity to shift to further support export and import competing industries, which almost certainly entails a reduced contribution from consumption and an increased contribution from net exports. We have the former, but I believe the impact of the latter has so far been insufficient to push the structural change along. As to why that is not occurring more quickly, I will hand the microphone over to Michael Pettis.

The interesting footnote here is the role of the fiscal deficit. Additional fiscal spending could reduce unemployment, but would it come with a wider trade deficit? I think it would – meaning that a portion of additional stimulus would bleed out overseas. And this, I think, is one reason the Administration is comfortable with risking the consequences of additional fiscal contraction. Instead, they look for fiscal policy to support the rebalancing story, and thus maintain the confidence of foreign investors. (That and I get the sense they are trying to recreate the mid-90’s, which seems unlikely given that it was a very different economy.)

All of which leaves me with these thoughts: While not discounting the probability that some structural factors are at play, the primary challenge facing the US economy is insufficient demand. Optimally, I think the best solution to this challenge is that demand emerges from the external sector – and here I mean NET exports, export and import competing industries. This source of demand would support needed structural change, ultimately for the good of the US and global economies. This adjustment requires a relatively complicated expenditure-switching story on a global basis. I don’t know how to avoid such a story. Barring this outcome, one falls back on fiscal policy, which can surely do the job, but risks maintaining the current pattern of global imbalances. And perhaps such concerns are overblown; after all, so far the fears of a Dollar/current account crisis have not emerged. Indeed, despite the ongoing debate in Washington regarding the debt ceiling, it looks like foreigners (central banks?) continue to acquire US Treasuries.

In the end, I take something of a middle road. I don’t think we need sudden withdrawal of fiscal stimulus, although that appears to be what is happening. More appropriate would be near term expansion of fiscal stimulus sufficient at least to support the social safety net while allowing for an expenditure-switching story to build. But perhaps there are just too many moving pieces in such a plan to allow it to actually come to fruition. My fallback then is that we should not allow the reality of economic pain to take precedence over only imagined externally generated crisis.

Leave a Reply