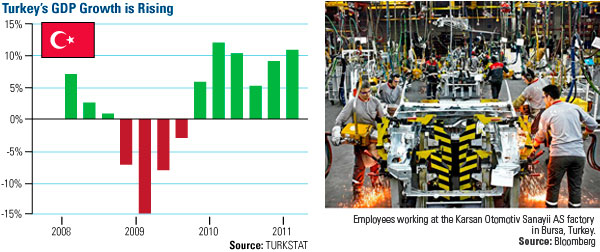

While much of Europe’s economy remains stuck in the mud, Turkey expanded 11 percent during the first quarter of 2011. In fact, Turkey’s economic growth outpaced China’s this quarter and most of the world’s larger economies last year, leading The Wall Street Journal to declare the country “Eurasia’s rising tiger.” Despite the acclaim, many investors have yet to warm up to Turkey.

We’re not one of them.

Turkey carries the second-largest country weighting in our Eastern European Fund (EUROX) and two members of our investment team were on the ground in Istanbul this week. They sat down with other money managers, analysts and company executives to expand their understanding of Turkey’s opportunities and find answers to pressing questions regarding the economy.

Our director of research, John Derrick, reported that there is substantial concern surrounding Turkey’s monetary policy. Even as the economy is revving up, the Turkish central bank refuses to raise rates because they expect inflation to slow. Tim Steinle, co-portfolio manager of EUROX, echoed that sentiment, adding that, following the re-election of Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan, it became clear that the central bank’s dovish stance was not election-year populism, but a firm policy choice.

This approach is clearly viewed as unorthodox. One bank argued that the central bank needs to immediately raise interest rates by as much as 400 basis points. The general consensus is the central bank should be more straight-forward and comprehensive to address the current account deficit (CAD).

Tim says that raising interest rates would be self-defeating at this point. Instead of stemming off money flows, it would enable a carry trade, meaning that it allows investors to sell a certain currency with a relatively low interest rate and use those funds to purchase a different currency yielding a higher interest rate. While it’s not the stated goal of the central bank policy, weaker currency is a direct way to address the CAD.

The country’s sizable deficit, which is currently 8.3 percent of GDP, means Turkey imported far more goods, services and transfers than it exported. This was due to strong domestic demand and components they needed to import only to then turn around and export. Tim pointed out rapid growth and capital inflows are good problems to have, compared with European neighbors. Now it becomes a matter of managing growth.

Due to the central bank’s current policies, quite a bit of repricing has already taken place and most banks are well prepared for rate increases if they ever come, as assets will now adjust by more than their liabilities going forward. Most are also seeing an increase in fee revenue, which is likely to offset the increase in funding costs. Non-performing loans are generally covered near 100 percent and capital ratios remain very strong.

The bank regulator, BRSF, has more or less imposed a 25 percent cap on loan growth this year. For the first half of the year, loan growth was about 36 percent; due to the restrictions, loans should slow materially during the second half. Also, for banks with more than 20 percent of loans from their consumers, the BRSF imposed an additional provision on consumer loans. Now the banks are on board.

In all, we’ve reaffirmed our longstanding positive view of Turkey (Read: Turkey as a Model of Middle East Stability). John says it’s a positive sign the country’s debt compared to its GDP has been decreasing. Fiscally, he believes the country is in good shape. Turkey also has a young demographic and a growing consumer class who’s already emerged. That’s our macro view.

On a micro, stock selection basis, John, Tim and the rest of the investment team are focused on quality companies with solid management teams that can offer the best returns on capital and growth at a reasonable price. Tying our macro view with bottom-up analysis is how we believe the fund has generated solid results for our long-term shareholders.

See which U.S. Global Funds Finished in the Top 30 for the Past 10 Years.

Leave a Reply