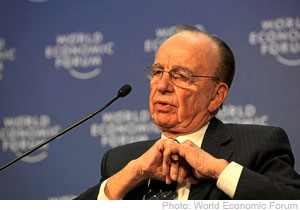

A lot of people detest Rupert Murdoch for a lot of reasons, but the biggest reason is that he gives us what we want.

A lot of people detest Rupert Murdoch for a lot of reasons, but the biggest reason is that he gives us what we want.

Before reality television took over our nights, Fox pioneered the idea that prime-tine network television could do without expensive professional actors and writers. If you want your news with a right-wing slant, Fox News Channel, which dominates its field, was built for you. How about serious journalism, with an emphasis on business, economics and politics, but with a decent attention to general news and the arts and sciences? The Wall Street Journal has been at least as good as it’s ever been, if not better, at providing this highbrow coverage since Murdoch’s News Corp. acquired its publisher, Dow Jones. And if the New York Post’s Page 6 did not invent the American gossip column, it pretty much perfected it.

Most Americans had never heard of the Australian-born publisher before 1976, when he acquired the Post. At the time it was a flailing, liberal evening paper whose best days pretty much coincided with its founding by Alexander Hamilton in 1801. Murdoch soon stamped it with his conservative politics, his flair for celebrity-chasing, and some of the most in-your-face tabloid headlines ever written. (“Headless Body In Topless Bar” is a 1982 classic.)

Murdoch did not believe in wasting space on long think-pieces that nobody wanted to read. If you picked up the Post for your train ride home from work, you could not even pretend you were doing it to broaden your intellectual horizons. You had to own up to the fact that you wanted to buy exactly what he was selling, which was nothing to brag about.

This is how Murdoch built a global media empire from a small family newspaper business Down Under. He operates on a simple quid pro quo: He delivers what people want, and he gets what he wants in return. So when Murdoch needed a waiver of Federal Communications Commission rules in order to buy TV stations in U.S. cities where he also owned major dailies, he got it. And when he needed American citizenship so he could retain and expand his broadcasting holdings here, including establishing the Fox network, he got that too.

Murdoch is back in the global spotlight today not because of his activities in the United States, but because of the phone-hacking scandal that engulfed, and ultimately destroyed, Britain’s News of the World. Murdoch’s son James, the chief executive of News Corp.’s European operations, announced yesterday that the 168-year-old title will cease publishing after Sunday’s forthcoming edition.

The British scandal has taken give-‘em-what-they-want reporting (if you can call it reporting) to depths we have never seen on this side of the pond. The Guardian alleged on Monday that News of the World hacked a phone that belonged to murdered teenager Milly Dowler, deleting voice mails from Dowler and interfering with police investigation of the crime. On Tuesday, The Telegraph reported that police believed the paper also broke into voice mail accounts of victims of the London transit bombings on July 7, 2005, as well as family members of troops killed in Afghanistan.

All of Britain seems to be in an uproar over these assaults on the privacy and dignity of private citizens. This is somewhat odd, because it is not exactly news that News of the World hacked into voice mails. The paper’s royal editor and two associates were charged nearly five years ago with hacking into phone accounts associated with Britain’s royal family. A variety of politicians, sports stars and other public figures were identified two summers ago as probable victims of the hack attacks. Yet the slowly building outrage over the affair did not reach a crescendo that forced News Corp. to act until this week’s revelations.

It might be fair to conclude that if British readers were bothered by the earlier disclosures that people deemed gossip-worthy were hacked, they not so bothered that they would give up their guilty pleasure of reading News of the World. The paper remained Britain’s largest seller, at around 2.6 million copies, right up to last week’s penultimate issue. To the end, Murdoch and his associates were giving the public what it wanted.

This Sunday’s edition will run without advertisements, in large part due to the flight of advertisers in the wake of the allegations.

Killing News of the World is a simple and effective business decision for News Corp. At one stroke, the company can appear to be responding with appropriate vigor to the scandal without actually giving up much in the way of profit. Like most newspapers, the tabloid was not generating much, if any, income or cash flow these days. By making it look as though it takes the matter seriously, News Corp. no doubt hopes to defuse opposition in Britain’s Parliament to its planned takeover of British Sky Broadcasting, which is worth far more to the company than News of the World.

News Corp. is already positioning itself to try to reclaim those Sunday readers by launching a Sunday edition of NOTW’s tabloid stablemate, The Sun. The Mirror reported that News Corp. reserved several appropriate domain names, including TheSunonSunday.com and TheSunonSunday.co.uk, earlier this week. This was several days before James Murdoch announced the shutdown of News of the World.

Cynicism about News Corp.’s move is further fueled by the news that, while some 200 journalists will lose jobs at News of the World, one person not immediately headed to the unemployment line is Rebekah Brooks. She is the chief executive of News International, the News Corp.-owned publisher of News of the World, and she was News of the World’s editor when the Milly Dowler disappearance broke. Brooks, who is close to both Rupert Murdoch and Prime Minister David Cameron, claims that it was “inconceivable” that she “knew, or worse sanctioned” the activity.

That Murdoch would kill the paper without firing the executive who was in charge of it speaks volumes about his priorities. News of the World is now more trouble than it is worth, so it has to go. But Brooks is an executive who knows what the public wants and is prepared to give it to them. That makes her a keeper.

Sometimes a brand becomes so damaged that it can no longer survive. It happened to Arthur Andersen, where I started my finance career, when the accounting firm was indicted following the collapse of Enron. Though the Supreme Court later threw out the case, the damage was long since done.

More charges are going to follow in the News of the World case. Journalist Andy Coulson, who departed as the paper’s editor and became Cameron’s chief spokesman before resigning earlier this year, reportedly turned himself in earlier today, and other individual participants may be charged as well. Maybe convictions will result, or maybe not. Either way, the rapid unraveling of the paper is a reminder of how the actions of a few can bring down a large enterprise.

All of the outrage and all of the charges are not going to make a bit of difference in the way News Corp. and its chief executive do business. Rupert Murdoch will continue to insist on giving us what we want, whether we want to admit it or not.

- Bulenox: Get 45% to 91% OFF ... Use Discount Code: UNO

- Risk Our Money Not Yours | Get 50% to 90% OFF ... Use Discount Code: MMBVBKSM

Disclaimer: This page contains affiliate links. If you choose to make a purchase after clicking a link, we may receive a commission at no additional cost to you. Thank you for your support!

Leave a Reply