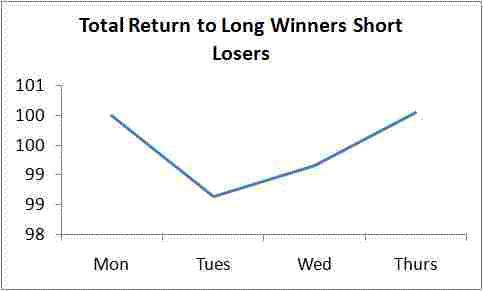

Above are the returns (based at 100) for a portfolio long the top 50 winners, short the bottom 50 losers. US stocks, market cap over $500MM as of Monday.

I remember reading about this end of year strategy a while back: go long year-to-day winners in December, short year-to-day losers, in December. As winners have tax gains, and losers tax losses, there is good theoretical reason why such portfolios should have different returns in December on a partial equilibrium basis. Why take a taxable gain in December, when you can postpone it until the next year? Why not take the taxable loss now? If all the winners have hesitant sellers, the losers willing sellers, winners should outperform losers in December. They did for decades.

With theory and data, I put on this trade in 2003, and got destroyed. In my personal backtests at that time, where I also did market cap and other (clever) filters, it had an extremely good history, losing only a couple of times over the prior 30 years. Of course, I had an out-of-sample adverse experience.

This highlights that even if you can articulate a strategy that make sense, over time it will disappear regardless. This is why having an ‘equilibrium’ result for some tendency is important for a strategy everyone knows about, because if it’s not, it’s probably an epiphenomenon, like noting that internet companies are good shorts (true if you have 2001 prominent in your sample).

Index additions/deletions, low price stocks, all these have been arbitraged out of the market after they were discovered. It’s best to simply not play a game that brokers send to traders in white papers if it is based on being clever, because brokers are not clever, but rather conventional wisdom.

Leave a Reply