Last week the National Center for Health Statistics announced that U.S. life expectancy had fallen slightly in 2008 to 77.8 years, versus 77.9 years in 2007. Clearly this decline was related to the recession, in some way. Nevertheless, it struck me as odd that in the same year life expectancy declined, employment in the private healthcare sector rose by 2.7%, faster than the 10-year average growth rate.

That observation made me think (again) about putting together a simple analysis of healthcare productivity. I understand quite well that this is a quixotic venture, since productivity is defined as output per worker and no one can agree on how to measure the output of the healthcare sector is. But I’m going to take it step by step, for transparency. Everyone is welcome to lob tomatoes, as desired.

Let’s start from the beginning. We don’t have a good measure of the output of the healthcare sector. However, population size is clearly related in some way to healthcare output (for a given level of ‘health’, we’d expect the output of the healthcare sector to rise with the population, holding demographic and income composition constant).

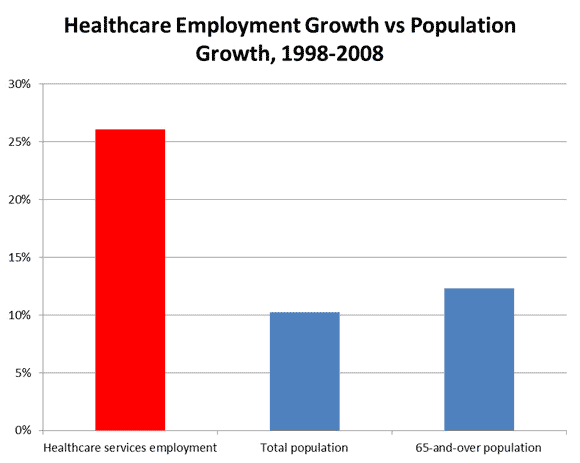

So here’s our first step. The chart below compares the 10-year employment growth in private health care services with overall population growth, and with growth of the 65-and-over population.

If productivity in the healthcare sector was rising, and the “health output” per American, however defined, was constant, then we would expect healthcare employment to rise slower than the population.

But in fact, you can see that healthcare employment increased much more than the overall population from 1998 to 2008. (26% vs 10%). FYI, the same was true during the recession–from 2007 to 2010, healthcare employment rose by about 6%, while the population rose by slightly less than 3%).

More important, the increase in healthcare employment also far outstripped the increase in older Americans (a 12% gain). That means the big growth in healthcare employment cannot be due to the aging of the population.

So in fact, we’ve already learned something. The rapid increase in healthcare workers per capita is by itself a key reason for rising healthcare costs–separate from the cost of new drugs, the capital expense for new technology, and the aging of the population.

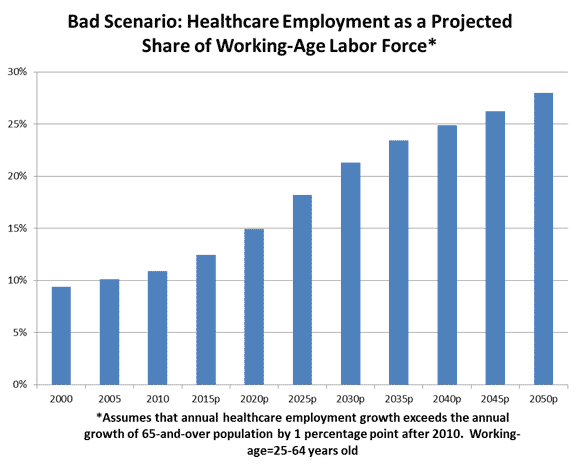

During the recession, having healthcare as a steady source of employment growth has been a godsend. However, this is not sustainable over the long run. Suppose that the employment pattern of the past ten years is maintained in the future, so that the annual growth rate of healthcare employment exceeds the growth rate of older Americans by 1 percentage point. The following chart shows private sector healthcare employment as a share of the working age laborforce (age 25-64).

If things keep going the way they’ve been, healthcare will employ almost 30% of the working-age labor force by 2050. That’s not possible.

To put it a different way: Over the long run, we’re screwed unless we reduce the growth rate of healthcare employment down close to the growth rate of the older population. We just won’t have enough workers to care for all the old folks.

Labor is the real long-term issue around Medicare, Medicaid and other medical entitlements. Not share of GDP. Not the cost of medical technology or the price of drugs. You can bring down payments to drug and medical device companies and doctors all you want, but unless you dramatically increase the growth rate of ‘output per worker’ in healthcare, we will still end up in trouble. This is why ‘cost controls’ have failed to stem the rise of healthcare costs.

Final implication: History suggests that investment in physical capital, technology, and R&D is the best way to increase the growth rate of “output per worker” in an industry. And in fact, capital stock per worker in healthcare has lagged the rest of the economy….but that’s a different post.

Leave a Reply