The Consumer Price Index (CPI) rose by just 0.2% in October, up from 0.1% September, but down from increases of 0.3% in August and July. Year over year, it is up just 1.2%. Almost all of the increase was due to energy prices, which rose 2.6% after increases of 0.7% in September and 2.3% in August. Year over year, energy prices are up 5.9%.

Actually the increase is even narrower than that, as energy commodities such as gasoline were up 4.4% after increases of 1.8% in September and a 3.8% increase in August. That is much higher than inflation in the rest of the economy. The relative pricing strength in energy commodities suggests that it would be a good idea to be over weighted in the energy sector.

Energy service prices, like electricity and piped gas service actually rose by just 0.2% after falling by 0.8% in September. In August it increased just 0.2%. Year over year, energy services prices are a very well behaved, rising just 0.9%.

Food prices were also relatively well behaved, rising just 0.1% after being up 0.3% in September and 0.2% in August. Year over year, food prices are up 1.4%. Due to poor harvests in several important areas of the world — most notably due to droughts in Russia, and floods in Pakistan — agricultural commodity prices have been rising sharply, although they have recently backed off. So far they have had relatively little impact on Consumers shopping at Kroger’s (KR).

The actual cost of raw wheat is a very small fraction of the actual cost of a loaf of bread, so one would not want to exaggerate the likely impact of higher prices in the commodity pits on prices at the checkout counter.

Core Inflation

Thus, if one strips out the volatile food and energy prices to get to core inflation, prices were unchanged, the third straight month of being unchanged. Year over year, core prices are up 0.6%. Over the last three months, the increase annualizes to 0.0%.

While everyone consumes food and energy, their prices tend to be extremely volatile, and can be influenced by external events. As such, the Fed tends to focus more on core prices when setting monetary policy. After all, it would not be a good idea to be tightening up on the money supply or raising interest rates simply because there is a drought in a key agricultural area of the world which drives up food prices, or because there is instability in the Middle East which causes energy prices to rise.

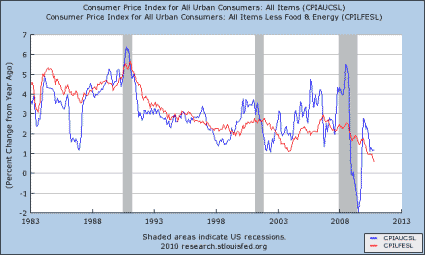

Together food and energy make up just 22.3% of the total CPI. The graph below tracks the long-term history of the CPI (year over year change) on both a headline and a core basis. Note that core CPI is at an all-time low for the period on the graph (and I cut out the really high inflation 1970’s so you could get a better sense of the more recent movements). The year-over-year change in core CPI is at a record low level, and records go back to 1957.

Another Report Vindicating QE2

This report is a vindication of the Fed decision to undertake another round of quantitative easing. The danger of QE2 is that it could set off a round of inflation; many critics say “hyperinflation.” That, however, is not the danger the economy faces, deflation is.

Deflation is a very nasty beast, and one that the Fed must stop from emerging at all costs. At any given level it is far more insidious than inflation; we can and have done reasonably well as an economy with 3 or 4% inflation, but 3 or 4% annual deflation would be an economic nightmare.

For starters, nominal interest rates do not go below 0.0%, which means that real interest rates rise sharply. That will choke off capital investment in the economy. At the same time, if people know that prices are going to be lower in the future than they are now, they will sit on their wallets. Total demand will fall.

With no customers, since they are all sitting and waiting for prices to go down, businesses will have even less reason to invest and will have need of fewer employees. The resulting layoffs will result in still less aggregate demand. Lather, Rinse, Repeat.

Housing Keeping Core Levels Low

The key reason why the core CPI has been so low of late is the cost of shelter. Housing prices are not measured directly through a housing price index like Case-Schiller. Instead, the government tries to measure just how much it would cost you to rent a house equivalent to the house you own next door to it.

This is known as Owner’s Equivalent Rent (OER). It makes up 25.21% of the CPI, or more than food and energy combined. Regular rent, paid by tenants to landlords, makes up another 5.97% of the overall CPI. The two rent measures tend to move closely together and combined make up 31.2% of the overall CPI, and since you neither eat nor burn your house (unless you are an arsonist committing insurance fraud) they make up an even larger part of the core CPI, 40.1%.

Regular rent rose just 0.1% in both October and September, reversing a 0.1% decline in August. Over the last year it is up just 0.3%. OER was also up just 0.1% after being unchanged in each of the last two months. Year over year, OER — by far the most important single part of the CPI — is unchanged.

The use of OER, rather than directly tracking housing prices, makes for a much more stable CPI. If housing prices were directly measured — using the Case Schiller index, for example — inflation early in the decade would have been running at levels close to what we saw in the 1970’s, and over the past few years as the housing bubble burst, we would be experiencing severe outright deflation in the core CPI.

Deflation Fears Keeping T-Note Yields Low

Right now, the risk of deflation is greater than the risk of run away inflation. We are not in it yet, at least as measured by core prices, but we are uncomfortably close. The threat of deflation is one of the reasons that long term T-note yields are so low. A return of under 2.9% per year is not very enticing for locking up your money for ten years.

If inflation were to average over the next ten years what it has averaged over the last ten years (2.5%) the increased amount of goods and services you could get for delaying your gratification for a decade would be almost nothing. If it were to average what it has since 1983 (the period covered by the graph above — 3.0% for both core and headline) you would actually lose purchasing power by locking up your money.

At the first hint that inflation is picking up, bond yields can be expected to head much higher. Even though I think that deflation is a greater threat right now than a return to the high inflation of the 1970’s, I do not think that the Fed will allow it to happen.

Deflation is the only scenario under which the purchase of long-term treasuries makes sense at these levels. To buy a T-note, you have to be rooting for breadlines and Hoovervilles. A good way to bet on T-note yields rising is the short treasury ETF (TBT).

Where Prices Are Increasing

So what areas are showing price increases? Health care costs always seem to run faster than overall inflation, but even they seem relatively well behaved. Medical commodity prices (i.e. drugs) were up just 0.1% in October after a 0.3% rise in September, and a 0.2% increase in August. Year over year they were up 2.5%.

Part of the reason for that is probably the increasing substitution of generic drugs for name-brand prescriptions. While prices of drugs still on-patent for firms like Pfizer (PFE) and Merck (MRK) are still aggressively rising, they are now losing share to their slightly older drugs that are no longer state-enforced monopolies and have to face the free market.

Medical services prices (i.e. a visit to the hospital) rose 0.2% after they jumped 0.8% in September. But that was after a 0.2% rise in August and after being unchanged in July. Year over year, medical service prices are up 3.6%. That is still higher than the inflation rate elsewhere in the economy, but is far below the average rate of medical inflation in recent decades.

The taming of medical inflation is vitally important, as rapidly rising health care costs are the primary factor in the long-term structural budget deficit. It is the long-term structural deficit that we have to be worried about, not the current big deficit that is mostly due to cyclical factors (reduction in tax revenues and higher automatic stabilizer costs due to high unemployment).

The other noteworthy area of inflation is in car prices, particularly used car prices. That finally changed for the better in September, as they fell 0.7%. That continued this month with a 0.9% decline. Still, we are talking about a 8.9% rise over the last year.

The price of new cars fell 0.2% in October after rising just 0.1% in September and 0.3% August. Year over year, new car prices are up 0.4%. In other words, the remarkable resurgence in the Auto industry, as symbolized by the massive GM IPO today, was not simply due to the car companies being able to jack up prices.

The differential between new and used car prices was obviously unsustainable. If it were to continue for a few more years, a 1999 Ford (F) Escort would cost more than a new Ford Focus. Somehow I don’t see that happening.

The narrowing of the difference is probably bad news for the big used car dealers like CarMax (KMX). What we were probably seeing is a large “inferior good” effect. In other words, in tough times, people gravitate to buying the cheaper product, even if is of inferior quality. Used cars relative to new cars meet that description.

Fairly Solid Report

Overall this was a fairly solid report. It does not totally put to bed the danger of deflation. However, this is October data from before the Fed started to actually implement QE2 (although the move was well telegraphed). It certainly does not raise the specter of runaway inflation any time soon. It vindicates the Fed’s decision to go ahead with QE2.

QE2 is bullish for stocks and commodities, a mixed bag for bonds (the additional buying pressure from the Fed would reduce yields, but to the extent that QE2 raises expectations for inflation going forward, long-term yields would tend to rise). It should bearish for the dollar (and thus bullish for other currencies), but so far the effect seems to have been swamped by renewed concerns over the Euro due to the Irish (and potentially Portuguese, and Spanish) debt situation(s).

QE2 should end the risk of outright deflation, and at the margin should help the overall economy. Don’t expect it to have a dramatic effect. It is a poor substitute for what the economy really needs — more fiscal stimulus — but that is simply not going to happen in the current political environment. Instead, fiscal policy is likely to head in the completely wrong direction starting in January, and the additional monetary stimulus will likely be offset by fiscal drag.

Leave a Reply