Justin Lahart is among those calling attention to the Billion Prices Project of MIT Professors Roberto Rigobon and Alberto Cavallo.

The basic idea of the Billion Prices Project is to automate search of websites around the world that report prices at which various vendors are offering to sell specific items. By comparing that price with that for the identical product posted the previous day by the same vendor, the MIT researchers obtain a measure of when and by how much each price changes. This is of interest both for economic theories about the nature of price changes and for providing up-to-date real-time assessments of broader inflation trends.

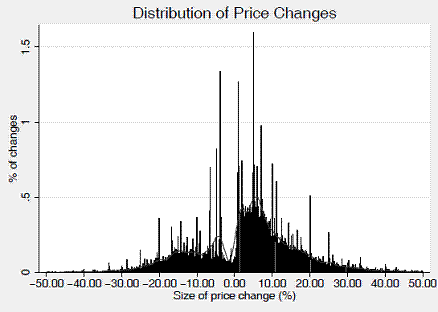

From the perspective of economic theory, one of the project’s most interesting findings is that when vendors change the price, they are more likely to make a large change rather than a small one, giving the distribution of price changes a bimodal shape. This is in contrast to earlier research using scanner sales data or individual CPI components, which had suggested that small price changes were quite common.

Histogram (bin size = 0.1%) and smoothed kernel density estimate for distribution of daily price changes for Argentina. Source: Cavallo (2010).

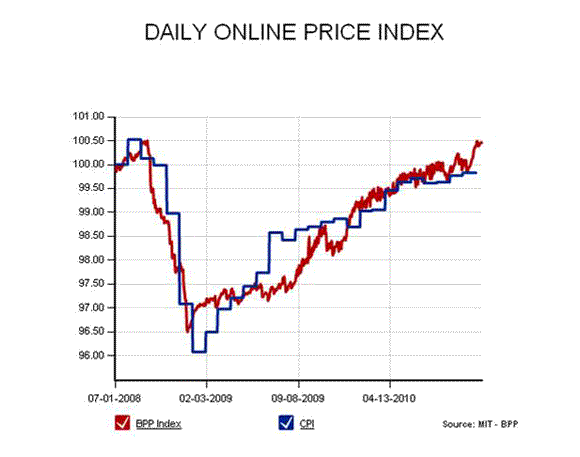

It’s also interesting to look at the overall price indexes that come out of these data. Cavallo and Rigobon’s approach is to take an arithmetic average of all the observed price changes for each day. They then paste today’s average price change together with yesterday’s and the day before’s to get a measure of the cumulative overall price change since some base date. This differs from a measure like the consumer price index in a number of ways. Whereas the CPI tries to measure the change in price of a particular “market basket” purchased by a representative consumer, the BPP is measuring just the price changes in observed comparable items with a sample that is dynamically changing every day based on the entry and exit of products. BPP leaves out important components that the CPI tries to include, such as housing services and technological improvements, though the ways that the CPI handles these issues are imperfect and controversial. The BPP also excludes important items such as fuel, and makes no allowance for seasonal factors. On the other hand, those items covered by the BPP may be measured more accurately. A particular advantage of BPP is that it’s available daily and for countries for which other inflation measures may be particularly problematic. And despite the conceptual differences from the CPI, it seems to give a similar overall reading.

BPP and seasonally unadjusted consumer price indexes for the United States. Source: Billion Prices Project.

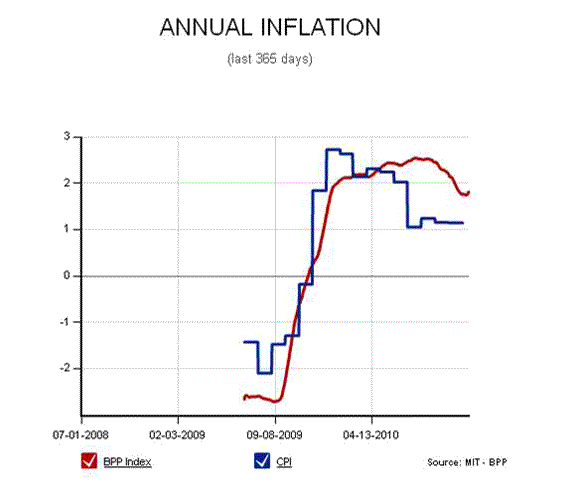

In terms of the latest trends, the BPP confirms the impression from the CPI that U.S. inflation has dropped back below 2%, though the BPP numbers have recently been tracking slightly above the CPI.

BPP and CPI inflation rates for the United States. Source: Billion Prices Project.

Leave a Reply