Exports in March dropped a less-than-expected 17.1% from the same time last year – below expectations of 20% and the 21.1% drop for the first two months of 2009. Most of the articles I read in the Chinese and foreign press including, not surprisingly, comments from the customs bureau, hailed this as a sign that the export slump is bottoming out. According to an article in Saturday’s South China Morning Post, for example:

Many economists said the export slump of the past five months was finally showing signs of abating, with the Administration of Customs describing the latest export figures as a “marked improvement”. However, they cautioned that imports would remain weak in the near future, overshadowed by prevailing low commodity prices and the de-stocking of mainland factories and overseas importers.

“It is the beginning of stabilisation,” Citibank economist Ken Peng said yesterday. “We should have seen stronger import numbers last month. We had more money in place, but we’re not importing more and that’s surprising.”

A Bloomberg article had the following:

The “collapse of global trade and China’s exports in the last few months was not in small part due to a freeze in trade credit and aggressive de-stocking abroad as a result of extreme uncertainty,” said Wang Tao, an economist at UBS AG in Beijing. “As expectations start to stabilize, we expect to see export orders rebound in the coming months.”

I guess that different people have radically different ways of forecasting export growth. To me, it is completely meaningless to look at recent trends in China’s export performance in order to forecast the future. The only thing that matters is what will happen to net demand from the trade deficit countries – most of which is represented by US net demand – and so the recent improvement in China’s export performance (not really an improvement, of course, but an improvement in the rate at which it is deteriorating) really tells us very little.

The real question is will US gross and net demand continue to contract? Almost every serious economist I have spoken to believes that it will, with disagreements only on the speed, intensity and duration of the contraction. Someone whose blog I have been reading a lot lately (I like him because, aside from his Minsky-Fischer orientation, he has the audacity to claim that if you don’t know economic history then you don’t know economics and, what’s worse, he even insists that history extends to beyond the past twenty years), University of Western Sydney professor Steve Keen, suggests that from what he calls a non-orthodox, Hyman-Minsky point of view we should think of aggregate demand as “the sum of GDP plus the change in debt.”

That sounds right to me. Certainly debt accumulation seems to have represented the difference between the growth in US consumption and the growth in US GDP over the past decade, as I discussed in Wednesday’s post. If he is right, we should expect US consumption (and that of many other deficit countries, for that matter) to grow less than GDP by the amount of the deleveraging taking place. That is a lot of deleveraging.

In that case the export performance of countries like China can only get worse because the ability of deficit countries to consume China’s export of excess production will be contracting quickly, and in that light it doesn’t matter how successful you think the Chinese stimulus package may have been. Export growth depends on someone else’s import growth, which depends on their consumption growth, and in a world of contracting GDP, if consumption growth is even underperforming GDP growth, it is a little hard to be optimistic about export growth forecasts. The domestic stimulus is irrelevant.

Talking about the stimulus package, there has also been a lot of talk about its success as being evidenced by the way a number of indicators have bottomed out or even turned. Unfortunately it seems to me that most of those indicators fall into one of two groups. In some cases there were special circumstances that caused a surge, but whether the surge is sustainable, and in some cases whether it won’t be reversed in the future, is questionable. For example car sales have finally started to rise: China’s passenger car sales rose 10% in March from a year earlier. But this was after tax cuts and government subsidies boosted demand, and there are lots of rumors about government agencies and state-owned enterprises being persuaded to anticipate vehicle purchases. If that is the case, the surge in purchases may soon peter out, and in fact may slow sharply to the extent that planned purchases for later this year were accelerated.

The second group of positive indicators I would describe not as evidence that the fiscal stimulus is working but rather as evidence that some people are behaving as if they believe the fiscal stimulus will work. For example rising steel and concrete inventories and increased purchases of equipment suggest to me not that end demand has been created but rather that many producers are anticipating that end demand will be created. Perhaps they are right, in which case we should see more positive indicators in the future, but if they are wrong then we are likely to see nothing more than a temporary buildup that will have to be reversed.

But to get back to exports, China’s trade surplus for March was $18.6 billion. That sums to $62.6 billion for the first quarter, compared to $41.7 billion for the first quarter of 2008 and $114.3 billion for the last quarter of 2008. Although lower than the astonishing heights of January and late last year, the trade surplus is still much higher than this time last year. That means China’s export of overcapacity is still increasing, especially if you think, as I do, that February’s very low trade surplus ($5 billion), and possibly part of March’s, was caused by commodity accumulation to replenish strategic reserves.

More capacity?

In that light articles like this one from Friday’s Financial Times are not encouraging:

The aluminium industry has been hit hard by the global economic crisis with sharp falls in sales across the automotive, construction and aerospace industries. …However, a recovery has emerged in recent weeks and prices are 18 per cent off their lows. The concern in the industry now is that the nascent recovery could be nipped in the bud because Chinese smelters are busy ramping up production at a time when demand is continuing to fall.

As China accounted for about 35 per cent of global aluminium production and consumption last year, its supply and demand developments are of huge significance for the world market. Industry leaders warn that the outlook for demand remains weak

…However, Wen Jiabao, China’s premier, has made it clear that Beijing will do whatever is needed to maintain economic growth at “about 8 per cent”. This has led to huge pressure on local governments to ensure growth targets are met. One result is that aluminium smelters have been offered tax cuts and subsidised bank loans to encourage production to restart.

Last year’s price crash forced China to close about 3.1m tonnes (22 per cent) of its total aluminium production capacity as many of the country’s smelters fell into the red. But analysts at Macquarie estimate that 500,000-600,000 tonnes of capacity has recently been restarted in Henan province. “Local government officials, especially in Henan, have been urging the aluminium industry [the key income tax payer of the province] to restart spare production capacity immediately,” says Bonnie Liu of Macquarie.

China’s government has also been providing significant levels of support to the domestic market. The State Reserves Bureau, which has already bought 590,000 tonnes, is expected to expand purchasing up to 1m tonnes. The State Grid Corporation has bought about 400,000 tonnes and provincial governments have indicated they will buy up to 900,000 tonnes.

Too many people who should know better assume that trade policies are limited to raising import tariffs or devaluing the currency, and since both of these were addressed in the recent G20 meeting, we can all more or less relax. This is wrong. Anything that alters the gap between total production and total consumption must have a trade impact, and if capacity is boosted in the face of falling demand, that is as likely to force up the trade surplus as import tariffs or currency devaluation.

I do not believe that will go on much longer. Over the next few months we should start seeing even more pressure on China’s exports as either trade friction or exhaustion (on the part of countries who have had to bear more than 100% of the brunt of the contraction in US demand) forces continued global demand contraction to switch to China.

How important will that be? Ever since The Economist came out with a consensus-busting piece last year that China is much less reliant on exports than many people think (whatever that means), well-informed people have been assuring each other that “China is much less reliant on exports than many people think.”

Maybe. But it is still very heavily reliant on exports. When your total production exceeds your total consumption by 7% of GDP (in the past 12 months China’s trade surplus was $320 billion, while its 2008 GDP was $4.3 trillion), you rely very heavily on foreign demand to absorb a big chunk of your output.

According to a recent Andrew Batson article in the Wall street Journal, a trio of researchers at the Hong Kong Monetary Authority revisits the whole question of China’s dependency on exports. I was not able to find the cited piece, so I can only limit myself to the comments in the article, but, and sorry for the long quote, here is what they find:

The paper builds on previous work by one of the authors, Li Cui, who in a 2007 working paper for the International Monetary Fund presented evidence that China was becoming more dependent on external demand over time. Indeed, net exports contributed about 20% of China’s economic growth from 2005 to 2007, compared to less than 10% in the previous five years. But the authors of the new paper try to go beyond that number to capture the total effect of the export manufacturing sector on the economy, including investment in new factories by exporters, and spending by people employed in those factories. That leads them to conclude that the spill-over effects from the export sector are in fact quite large.

The authors estimate that a decline of 10 percentage points in export growth would be associated with a decline of about 2.5 percentage points in GDP growth. “This is about at least twice as large as what could have been expected if only the direct impact of exports is considered,” they write. Part of the explanation, they say, is that exports are extremely important to a group of Chinese coastal provinces, which themselves account for the majority of the national economy. So changes in export demand can cause dramatic fluctuations in those regional economies, even while the inland provinces are less affected.

But of course, China’s exports have recently slowed by a lot more than 10 percentage points. In volume terms, export growth rates have swung from around positive 20% in 2007 to nearly negative 20% in the first part of this year. The biggest effect of a decline in exports, the authors find, is on corporate investment, as companies scale back expansion plans. And since the sharp drop in exports is just a few months old, the full magnitude of the subsequent drop in capital spending may not yet be evident.

Foreign currency reserves

Besides export numbers the other piece of important news for me was the release of first quarter reserve numbers. According to Xinhua’s account:

China’s foreign exchange reserves rose 16 percent year-on-year to 1.9537 trillion U.S. dollars by the end of March, said the People’s Bank of China on Saturday. It represents an increase of 7.7 billion dollars for the first quarter, but the increase was 146.2 billion dollars lower than the same period of last year.

In March alone, the foreign exchange reserves rose by 41.7 billion U.S. dollars. The increase was 6.7 billion U.S. dollars higher than the corresponding period of last year.

This is the smallest quarterly increase we’ve seen in a long time. The first quarter of 2008, for example, saw reserves grow by an astonishing $153.9 billion, and 2008’s fourth quarter, the weakest quarter of the year by far, nonetheless saw reserves up by $40.4 billion.

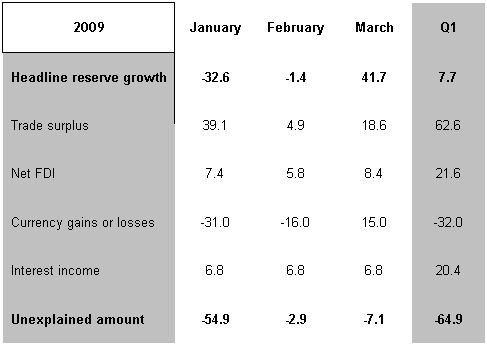

With Logan Wright’s help I put together the above table to try to understand what is going on with reserves. The key thing on which to focus is the “Unexplained amount,” which is a proxy for hot money inflows or outflows. Of course my estimates for currency gains or losses and for interest income are nothing more than estimates and may be, especially in the former case, substantially off.

Nonetheless the picture the table shows is pretty clear and pretty consistent with what we would expect. January, a time of deep gloom, saw a large unexplained outflow at least part of which may represent flight capital from nervous Chinese businessmen. Confidence seemed to rebound in February and March, with widespread (but to me doubtful) claims that the fiscal stimulus was “working” and with the stock market rocketing up. During that time unexplained out flows collapsed to nearly zero. The only conflicting evidence was reports in the Hong Kong press of a serious increase in the amount of currency transactions among border money changers, in which the number of Chinese buying US and Hong Kong dollars with RMB rose to suspiciously high levels.

The overall picture is consistent with two different and popular predictions. First, the stimulus package is working and that China will soon emerge from the worst of the crisis. Second, that the fiscal stimulus represents a risky bet on the duration of crisis abroad, and if sustainable and recovery in global demand does not occur in the next few quarters, it will set the stage for a deepr contraction late this year and next year.

Trade determines reserve currency status

Finally, for those who might be interested in today’s version of my biweekly South China Morning Post piece, here is the original, pre-edited version:

People’s Bank of China Governor Zhou Xiaochuan generated huge controversy when he argued two weeks ago in favor of an international reserve currency to cure distortions in the global balance of payments. Although his reasons for worrying about excessive reliance on the dollar were probably correct, his proposal for an alternative currency based on SDRs was more problematic.

The SDR is not a currency. It is an accounting unit based on an artificial currency “basket”. As of January 1, 2006, the SDR valuation basket had the following weights based on their roles in international trade and finance: U.S. dollar 44%, euro 34%, Japanese yen 11%, and pound sterling 11%.

If countries accumulated reserves in the form of SDRs, they would effectively accumulate a basket of the above currencies. But of course no one needs SDRs to accomplish the same thing directly. If the People’s Bank of China, for example, felt that the SDR represented a more balanced and appropriate portfolio composition for its reserve holdings, nothing could have prevented it from apportioning reserves according to the SDR basket.

And yet informed observers believe that the US dollar accounts for anywhere from 65% to 70% of the PBoC’s total direct reserve holdings – even more if we include foreign assets of state-owned enterprises and minimum reserves held by China’s commercial banks.

But if holding more than 44% of a country’s reserves in dollars distorts the global balance and creates excessive currency concentration, why do the People’s Bank of China and other central banks willingly do just that? Dark mutterings about US hegemonic power notwithstanding, there are no legal or physical restrictions on the ability of central banks to choose the assets they purchase. For the past decade they could easily have purchased fewer dollars assets and more euro, sterling and yen assets.

The answer has little to do with geopolitics. It is a necessary requirement in global trade that capital and trade flows balance. Countries running trade surpluses must recycle their surpluses to the countries running trade deficits. Normally this is done through private investment flows, but following the 1997 Asian crisis a number of central banks, especially in Asia, began accumulating such large amounts of international reserves that their purchases of foreign assets completely dwarfed private investment flows.

Assets which the central banks of trade surplus countries purchase will to a significant extent determine which countries run trade deficits. If central banks mostly buy US dollar assets, the US will run the corresponding trade deficit. Contrary to popular opinion, financing flows do not necessarily follow trade flows. It is often the other way around..

Let us assume that over the past decade Asian central banks had decided to acquire reserves in the amounts described by the composition of the SDR. This means, assuming trade surpluses were constant, that they would have purchased between one-half and two-thirds the amount of dollars they actually did. The balance would have gone into euro, yen and sterling.

One likely consequence is that with less demand the dollar would have been weaker relative to the other three currencies then it has been. This would have cause a relative expansion in the tradable goods sector of the US, and a relative contraction in the tradable goods sector of Europe and Japan. With the expansion in the US tradable goods sector, and its positive impact on employment, the Federal Reserve would have kept interest rates a little higher, and US consumption would have been a little lower relative to GDP. Of course the exact opposite would happen in Europe.

Lower consumption means lower imports, and vice versa, in which case the US trade deficit would have been lower and the European and Japanese trade deficits higher by roughly the difference in the amount of dollar reserves purchased. By choosing to buy euros instead of dollars, in other words, Asian central banks would have forced a large part of the US trade deficit to migrate to Europe.

But could Europe have sustained a large trade deficit for any long period of time? For both political and economic reasons too complex to discuss here, it is reasonable to assume that Europe would not have been able to bear the burden of a substantially larger trade deficit. Most Asian policymakers know this.

That is why the US dollar is the world’s reserve currency, and most especially the reserve currency of Asian countries using foreign demand to boost domestic growth. In the distorted trade environment of the post-1997 world, the US was the only economy large and flexible enough to absorb the trade deficits that Asian countries required for their growth. US hegemonic power or deliberations had very little to do with it. Asia had to accumulate dollars if it wanted foreign demand to power domestic growth, and SDRs would have prevented this from happening. That is probably a good thing for the world, but a bad thing for China and Asia.

Leave a Reply