One of the ideas that stuck in my head as an undergrad was the proposition that “inflation is always an everywhere a monetary phenomenon.” The idea is usually formalized by way of the Quantity Theory of Money (QTM) — or more precisely — the Quantity of Money Theory of the Price-Level. (QTM is not a theory of money, it is a theory of the price-level).

In its simplest version, the QTM asserts that the equilibrium price-level is roughly proportional to the outstanding supply of money (however defined). As inflation is the rate of change in the price-level, the phenomenon of inflation is attributed primarily to excessive growth in the money supply (typically viewed as being controlled by the monetary or fiscal authority). Stories of interwar hyperinflations and tight correlations between secular or cross-section plots of inflation against money growth is likely what cemented the idea in my head. As the teaching assistant was fond of telling us: “Inflation is caused by too much money chasing too few goods.” Well, duh.

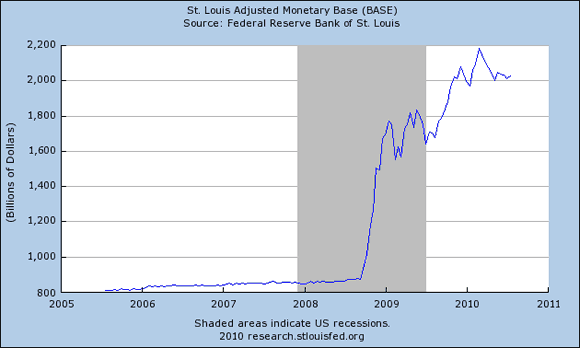

Alright then, let’s consider the following data, which plots the evolution of base money (money created by the central bank only) since 2005. No, this is not Zimbabwe…it is the United States. Since the fall of 2008, the Federal Reserve has more than doubled the supply of base money. Yikes! Is it time to buy gold and guns?

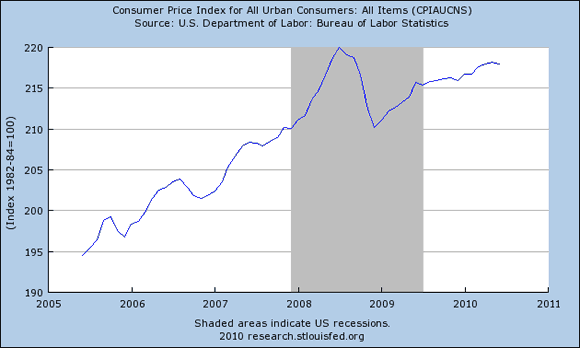

Well, maybe. Or maybe not (not yet, anyway). As the next figure shows, there is something conspicuously missing from the QTM story…where the heck is all that predicted inflation?

As Ron Paul is fond of stressing (ad nauseam) , the Fed creates (base) money out of thin air! It’s a puzzle that intrinsically useless fiat can possess market value in the first place. But given that it does, it is even more puzzling that doubling its supply does not halve its value (double the price level). What’s going on here?

The answer is that there are a lot of things going on. I can’t possibly talk about everything in one post, so let me focus on one thing here. The idea is this: perhaps the Fed is not simply creating money “out of thin air.”

The first figure above shows the evolution of the size of the Fed’s balance sheet (liabilities) over time. The following link shows the composition of the Fed’s balance sheet (asset side) over time: see here.

Normally, most of the Fed’s assets are in the form of U.S. treasuries (promises to pay future dollars). The Fed is currently holding about the same amount of treasuries as it did prior to the financial crisis. The doubling of assets we see today is attributable almost entirely to the Fed’s purchase of agency (Fannie and Freddie) debt in the form of mortgage-backed securities (MBS).

The first thing to stress is that the MBS purchased by the Fed did not consist of existing “toxic” assets. The purchases consisted of new-issues; that is, the highest rated mortgages made after the substantial decline in house prices. Moreover, it is my understanding that these products are essentially guaranteed by the Treasury. And indeed, the income generated by these purchases (rate of return roughly 5%) is in large part what allowed the Fed to remit an additional $25 billion to the treasury last year; see here.

Question: what sort of “bail out” generates $25 billion for the U.S. taxpayer?

So you see, the Fed did not simply create new money out of thin air. It created the money out of your mortgage, which in turn, is an income-generating security backed by a real asset (your home).

Now, we might all agree that creating fiat money and distributing it willy-nilly throughout the economy (helicopter drops) is ultimately inflationary. But this is not what is happening. It is by no means clear to me that an asset-swap of this form (money for MBS) is intrinsically inflationary. It all depends.

What does it depend on? Well, above all, it depends on the underlying quality of the assets backing the MBS. If these prime mortgages start to default en masse, then we have a de facto helicopter drop of cash, and this will be dilutive.

An analogy to keep in mind here is that of a company, say Microsoft, financing the purchase of new capital (say, a takeover of some smaller firm) by issuing new equity. New shares are created “out of thin air.” But is the new share issue dilutive (would it depress the purchasing power of existing shares)? The answer is that it depends. If the acquisition is accretive, then share value is likely to increase (the effect is deflationary). On the other hand, if the acquisition turns out to be a bust, the new share issue will be “inflationary.”

Note: one may want to argue that an increase in the supply of shares is not the same thing as an increase in the supply of Fed cash; the latter is relatively liquid (it circulates widely as a medium of exchange). But imagine that Microsoft shares also circulated widely as a medium of exchange…would this fact alone imply that the new share issue described above is necessarily dilutive? Money, like equity, is an asset; and its value (purchasing power) depends primarily (though not exclusively) on what backs it.

To sum up, the QTM may not be the best way to organize one’s thinking about the link between money and inflation. If you’d like to explore this idea further, I recommend that you take a look at Bruce Smith’s interesting piece: Money and Inflation in Colonial Massachussets. Here is the abstract:

This article argues that the quantity theory of money is not supported by the evidence. Contrary to the quantity theory, the article says, the value of money depends primarily on how carefully it is backed. That is, the rate of inflation depends more on underlying fiscal policies than on rates of money growth. The evidence for this argument comes from a close look at the way in which the colony of Massachusetts ended a severe long-term inflation in 1750. Other British North American colonies endured similar episodes, all of which parallel some periods of severe inflation in the 20th century United States. The 18th century

evidence thus contains lessons for modern monetary policy.

Further reading: Money as Stock (John Cochrane).

Milton Friedman would agree that increasing the supply of money is a major way to increase inflation. But the other part of that equation is the rate of spending (velocity). Many timest the wave of inflation does not set in for many years. It may be too early to tell right now, but inflation of the money supply ALWAYS leads to inflation in the long term. Your asset backed explanation is a nice observation though. Even with a doubling of the money supply, as long as the increase in the money supply matches the increase in value produced (very subjective) than we shouldn't see much inflation beyond the typical 2-4%. But that's if it matches. If it doesn't, we may as well be dropping it from a helicopter.

The Austrian view, if I can explain it correctly, is that inflation is the increase of the money supply, but an increase in the money supply does not necessarily create a rise in prices. A rise in prices would only occur assuming all else remains constant. It would be possible for there to be inflation without a rise in prices.

I think is also important to point out that the pre-Clinton era CPI is a far superior measure than the current government manipulated statistics.