The Greek crisis, which helped further extend the Dollar’s uptrend in place since the beginning of the year, is a reminder that global imbalances are still with us – and, if not corrected, will eventually threaten the sustainability of the global recovery. Indeed, how sustainable can any recovery be if the vast majority of nations are pursuing an export oriented growth strategy? After all, clearly that is not a game all can play – there needs to be a net importer to offset the net exports. Who wants to fill that role? If the US is pushed into filling that role, we have simply come full circle over the past three years.

The Administration is clearly aware of this challenge, but concerns are growing that any action will fall short of what is necessary to bring about real change. From Sudeep Reddy at the Wall Street Journal:

President Barack Obama’s goal of doubling U.S. exports over the next five years will be difficult to meet, business leaders and economists say, because of the lack of momentum on demolishing trade barriers and the shift by more American companies toward producing overseas.

U.S. exporters want Washington to put more pressure on trading partners to eliminate tariffs, crack down on intellectual-property violations and take a harder line on trading partners’ currency policies. American firms say stronger action by the federal government could substantially boost prospects for U.S. exports.

Policymakers argue that it is far too early to admit defeat:

Christina Romer, chair of the White House Council of Economic Advisers, calls the administration’s export target “an ambitious but reasonable goal.”

“Going up 100% over a five-year period is not such a radical idea when you think about historical experience,” she said, noting that exports increased more than 75% between 2003 and 2008. “It is going to be a gradual process. We are just starting the concrete steps in terms of what we can do to lower the fixed costs associated with exporting through trade promotion and commercial diplomacy.”

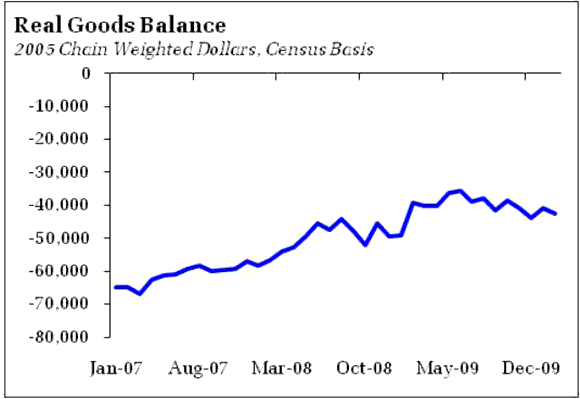

Am I the only one that finds the Administration’s focus on doubling exports somewhat disingenuous? Economic growth depends on net exports – doubling exports is a fine goal, as long as import growth is contained, such that the net effect is positive. But with the economy bouncing back, will import growth remain contained? Recent signs are not supportive – the recovery so far has ended the improvement in the real trade gap:

Moreover, Romer claims the process will be “gradual.” Will it be so gradual that US firms will resume expansion of overseas capacity at the expense of domestic production? Back to the Wall Street Journal:

But the shift by more U.S. companies toward producing goods overseas is one of the factors that makes doubling exports tougher. These firms have built more factories in fast-growing foreign countries to serve emerging markets, so they often supply the goods and services from an overseas arm—not by loading shipping containers in the U.S.

American businesses say they must contend with a long list of disadvantages, from higher tax rates than in many countries to rising costs for benefits such as health care. U.S. producers also say an artificially low Chinese currency makes Chinese goods especially cheap in foreign markets and therefore tougher competitors for American goods.

Once that production leaves, I suspect it is largely gone for good, barring a very large, sustained, and broad-based shift in the value of the Dollar. To be sure, the Administration is pressing China to revalue the renminbi, but the pace of any appreciation is likely to disappoint. Moreover, the uptrend in the Dollar raises a new concern. From Yves Smith:

A further source of trouble is political. If the euro continues on its expected slide and the pound is devalued, the dollar’s strength will put a major dent in the US ambitions to increase exports. Moreover, the rise in the greenback relative to other currencies will no doubt make China much more reluctant to revalue the renminbi against the dollar.

Also, further pressure on the Euro is likely necessary to compensate for the fiscal drag of deficit containment in the PIIGS. Note too that recent events are driving capital to the US, holding down interest rates. From the Wall Street Journal:

Mortgage rates stayed flat last week, rising just slightly to 5.08% from 5.04% one week earlier, according to the Mortgage Bankers Association. So far, the big rise in rates that some had expected when the Federal Reserve ended its mortgage-backed securities purchase program last month hasn’t materialized.

In fact, the instability in Europe amid looming debt woes for Greece and Portugal on Tuesday sent investors looking for safer assets such as the 10-year Treasury, to which fixed-rate mortgages are closely tied. That has helped to keep rates down.

Sustained low rates will help keep US demand from waning, so much the better for to fuel the flow of imports necessary to meet the needs and wants of US consumers (it is not coincidence that the trade deficit began improving when the faltering housing market took the steam off consumer spending). And, intriguingly, Japan looks ready to resume the export push. Also from the Wall Street Journal:

As many Japanese enjoy their annual “Golden Week” holidays starting Thursday, some of Japan’s economic ministers will be traveling to the U.S. and Asia to pitch what they hope will become a new driver of the nation’s growth: infrastructure exports.

Transport Minister Seiji Maehara will spend Thursday and Friday in Washington to promote Japan’s superfast bullet-train system as it chases part of President Barack Obama’s high-speed railway project, which has an initial $8 billion price tag. Central Japan Railway Co. is among the hopefuls on some projects.

Meanwhile, Economic Strategy Minister Yoshito Sengoku will be wooing officials in Vietnam to choose a consortium of Japanese nuclear-power companies over French and South Korean rivals. Vietnam last year approved a resolution to build its first two nuclear-power plants, estimated to cost about $10.5 billion at current rates.

“In the past, Japanese ministers were too proud to go out there and cheer for our companies as they worried about failing to deliver successful results,” Mr. Maehara said. “I intend to play the role of the top salesman for Japanese companies as their success equals the nation’s economic growth.”

Tokyo has begun a push to help Japanese companies win multibillion-dollar infrastructure projects abroad as its domestic economy continues to slump and a population decline threatens to sink demand further.

At the same time, rising environmental concerns in developed nations and rapid expansion of emerging economies are resulting in bumper crops of projects in areas like railways, nuclear power and clean energy.

“There is no growth for Japan unless we enhance exports,” says Hiroki Mitsumata, director of nuclear-energy policy at the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry. “No matter how superior our technology is, if it’s confined within Japan, it will become obsolete like the species in the Galapagos.”

Given the consistent global policy theme of “more exports,” at least one US firm recognizes the potential for disappointment with the Administration’s goal:

Todd Teske, chief executive of Briggs & Stratton Corp., a Wauwatosa, Wis.-based small-engine maker, says he is partly counting on more exports to rebuild his sales after the recent downturn. Briggs & Stratton already receives about a fifth of its $2 billion in revenue from sales abroad, particularly in Europe. Mr. Teske calls the U.S. goal of doubling exports a “lofty goal” and one worth pursuing. But he’s realistic. “It seems like every country or region wants to fuel their recovery plan with exports,” he said.

Bottom Line: My gut tells me that in any battle for export oriented growth, the US will come up the loser. When push comes to shove, the US will do nothing in response to the accumulation of dollar assets abroad. Ultimately, nations need to do more to support domestic demand to drive economic growth. But the risk is that as the broad global financial crisis continues to fade, nations will increasingly attempt to withdraw fiscal support for their economies – even more so with the Greece example now so vivid – and attempt to rely on external growth to compensate. It is not a game everyone can win. But if it deteriorates into competitive devaluations, it is a game everyone can lose.

- Bulenox: Get 45% to 91% OFF ... Use Discount Code: UNO

- Risk Our Money Not Yours | Get 50% to 90% OFF ... Use Discount Code: MMBVBKSM

Disclaimer: This page contains affiliate links. If you choose to make a purchase after clicking a link, we may receive a commission at no additional cost to you. Thank you for your support!

Leave a Reply