It is an article of faith among conservatives that the value-added tax is a money-machine that must be fought to the death. The Wall Street Journal, for example, continually argues against the VAT on the grounds that if we were ever to adopt such an insidious form of taxation we would very quickly become just like Europe, as if the entire continent is one big Gulag instead of someplace where by and large the people are just as free and prosperous as Americans.

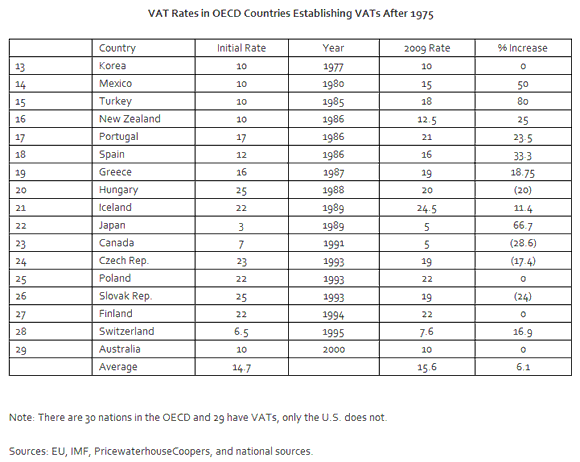

Today I just want to make two points about the money-machine argument. First, it is often implied that the trend of the VAT is continuously upward. This is factually wrong. According to the OECD, 7 of the 29 countries with a VAT have lower rates today than they had in the past: Canada, the Czech Republic, France, Hungary, Ireland, the Netherlands, and the Slovak Republic. And a number of countries have never increased their VAT rates: Australia, Finland, Korea, and Poland. Indeed, the average VAT rate in OECD countries is actually lower today than it was in 1984: 17.79 percent then versus 17.61 percent today.

In this respect it should also be noted that the VAT rates commonly referred to are statutory rates that don’t necessarily tell us anything about the effective tax rate. Conservatives just assume that the VAT covers everything and has the same structure in every country. In fact, every country with a VAT exempts many items, imposes lower rates on some things and higher rates on others. The rates one tends to see, such as those I use below, are the basic rates that apply to most things that a VAT covers. But the share of GDP covered by the VAT varies enormously from one country to another. I will post data on this point later.

Another problem with the money-machine argument is that it fails to note the critical impact of inflation on fueling higher VAT rates in the 1970s. At that time it was absurdly easy for governments to raise VAT rates because they were hardly noticed—what was another one percent rise in the inflation rate when the general price level was rising at double-digit rates? Furthermore, to the extent that inflation was a function of budget deficits, higher taxes were a plausible means of reducing it. And in the Keynesian model, higher taxes are inherently anti-inflationary because they reduce purchasing power.

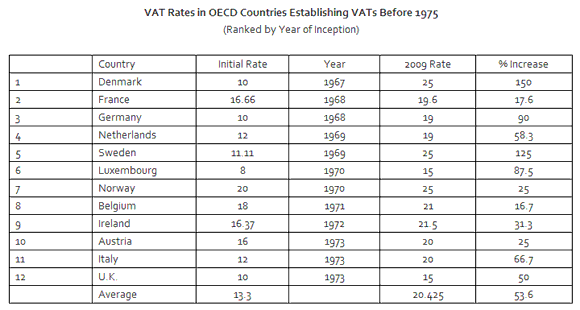

Therefore, I think it is critical that any money-machine analysis distinguish between those countries that adopted VATs before the great inflation of the 1970s and those adopting VATs in the era of relative price stability that we have seen since that time. I have done so in the two tables below. They show that to the extent that there is a valid money-machine argument it is only in the countries that were able to piggyback on inflation to ratchet up their rates in the 1970s. VAT rates show much less evidence of a ratchet effect during the era of price stability.

- Bulenox: Get 45% to 91% OFF ... Use Discount Code: UNO

- Risk Our Money Not Yours | Get 50% to 90% OFF ... Use Discount Code: MMBVBKSM

Disclaimer: This page contains affiliate links. If you choose to make a purchase after clicking a link, we may receive a commission at no additional cost to you. Thank you for your support!

Leave a Reply