In case you were just yesterday wondering if interest rates could get any lower, the answer was “yes”:

“The Treasury sold $44 billion of two-year notes at a yield of 0.802 percent, the lowest on record, as demand for the safety of U.S. government securities surges going into year-end.”

“Demand for safety” is not the most bullish sounding phrase, and it is not intended to be. It does, in fact, reflect an important but oft-neglected interest rate fundamental: Adjusting for inflation and risk, interest rates are low when times are tough. A bit more precisely, the levels of real interest rates are tied to the growth rate of the economy. When growth is slow, rates are low.

The intuition behind this point really is pretty simple. When the economy is struggling along—when consumer spending is muted and businesses’ taste for acquiring investment goods is restrained—the demand for loans sags. All else equal, interest rates fall. In the current environment, of course, that “all else equal” bit is tricky, but the latest from the Federal Reserve’s Senior Loan Officer Opinion Survey is informative:

“In the October survey, domestic banks indicated that they continued to tighten standards and terms over the past three months on all major types of loans to businesses and households. However, the net percentages of banks that tightened standards and terms for most loan categories continued to decline from the peaks reached late last year.”

Demand also appears to be quite weak:

“Demand for most major categories of loans at domestic banks reportedly continued to weaken, on balance, over the past three months.”

This economic fundamental is, in my opinion, a good way to make sense of the FOMC’s most recent statement:

“The Committee… continues to anticipate that economic conditions, including low rates of resource utilization, subdued inflation trends, and stable inflation expectations, are likely to warrant exceptionally low levels of the federal funds rate for an extended period.”

Not everyone is buying my story, of course, and there is a growing global chorus of folk who see a policy mistake at hand:

“Germany’s new finance minister has echoed Chinese warnings about the growing threat of fresh global asset price bubbles, fuelled by low US interest rates and a weak dollar.

“Wolfgang Schäuble’s comments highlight official concern in Europe that the risk of further financial market turbulence has been exacerbated by the exceptional steps taken by central banks and governments to combat the crisis.

“Last weekend, Liu Mingkang, China’s banking regulator, criticised the US Federal Reserve for fuelling the ‘dollar carry-trade’, in which investors borrow dollars at ultra-low interest rates and invest in higher-yielding assets abroad.”

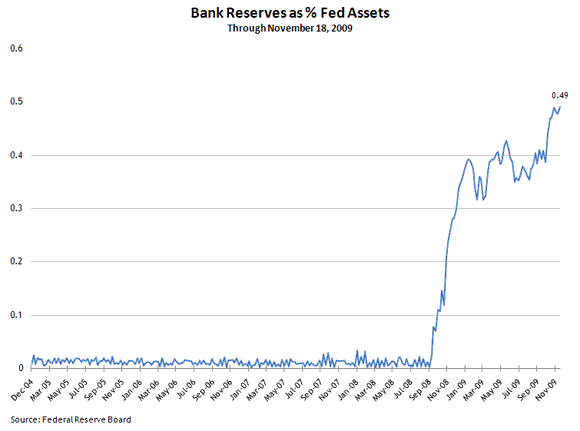

The fact that there is a lot of available liquidity is undeniable—the quantity of bank reserves remain on the rise:

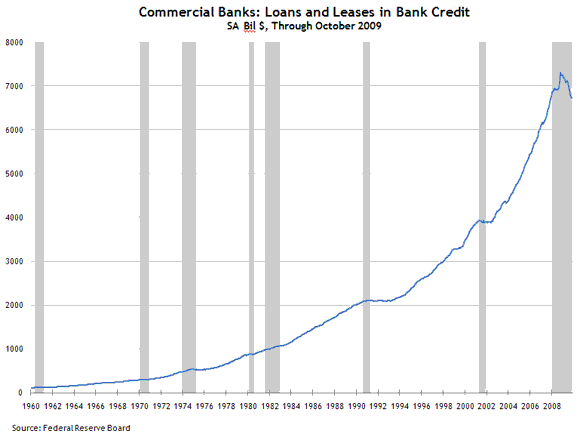

But the quantity of bank lending is decidedly not on the rise:

There are policy options at the central bank’s disposal, including raising short-term interest rates, which in current circumstances implies raising the interest paid on bank reserves. That approach would solve the problem of… what? Banks taking excess reserves and converting them into loans? That process provides the channel through which monetary policy works, and it hardly seems to be the problem. In raising interest rates paid on reserves the Fed, in my view, would risk a further slowdown in loan credit expansion and a further weakening of the economy. I suppose this slowdown would ultimately manifest itself in further downward pressure on yields across the financial asset landscape, but is this really what people want to do at this point in time?

If you ask me, it’s time to get “real,” pun intended—that is to ask questions about the fundamental sources of persistent low inflation and risk-adjusted interest rates (a phrase for which you may as well substitute U.S. Treasury yields). To be sure, the causes behind low Treasury rates are complex, and no responsible monetary policymaker would avoid examining the role of central bank rate decisions. But the road is going to eventually wind around to the point where we are confronted with the very basic issue that remains unresolved: Why is the global demand for real physical investment apparently out of line with patterns of global saving?

Disclaimer: This page contains affiliate links. If you choose to make a purchase after clicking a link, we may receive a commission at no additional cost to you. Thank you for your support!

Leave a Reply